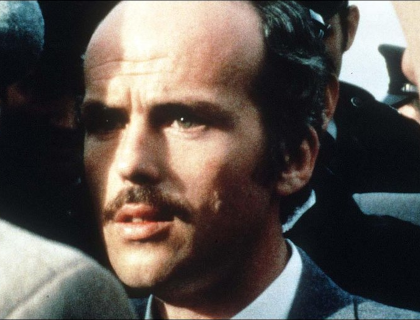

History is made on April 4, 2007, as Taoiseach Bertie Ahern and Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Ian Paisley shake hands for the first time in public prior to their milestone meeting at Farmleigh, the official Irish state guest house in Dublin.

Ahern is urged by Paisley to ensure that criminals who flee across the Irish border are arrested. The Democratic Unionist leader makes the proposal during a cordial one-and-a-half-hour meeting at Farmleigh in Phoenix Park, where the two leaders exchange their first public handshake.

Afterwards Paisley, who receives an invitation from the taoiseach to visit the Battle of the Boyne site later in the year, says that they had also discussed the need for the new administrations in Northern Ireland and in the Republic of Ireland to work for each other’s best interests. “We can confidently state that we are making progress to ensure our two countries can develop and grow side by side in the spirit of generous cooperation,” he declares. “I trust that old barriers and threats will be removed in my day. Business opportunities are flourishing. Genuine respect for the understanding of each other’s differences and, for that matter, similarities is now developing.”

Earlier the DUP leader, who becomes the First Minister of the new power-sharing government on May 8 alongside Sinn Féin‘s Martin McGuinness as deputy First Minister, firmly shakes the hand of Ahern in public for the first time. As he arrives at Farmleigh, he quips, “I better shake the hands of this man. I’ll give him a firm handshake.”

Paisley, who is accompanied by his son, Ian Paisley, Jr., affectionately grabs the taoiseach by the shoulder. There is another handshake after the meeting at Farmleigh is finished.

Paisley says, “Mr. Ahern has come to understand me as an Ulsterman of plain speech. He didn’t ever need a dictionary to find out what I was saying. We engaged in clear and plain speech about our hopes and our aspirations for the people we both serve. The prime minister kindly congratulated me on my election victory.”

Paisley says that he had raised a number of issues crucial to unionists. “I have taken the opportunity to raise with the prime minister a number of key matters including ensuring that fugitives from justice who seek to use the border to their advantage are quickly apprehended and returned without protracted legal wrangle.” He adds, “I raised other legal issues of interests to unionists, and we discussed cooperation of an economic nature that will be to our mutual benefit.” He also says he had raised the issue of bringing Northern Ireland’s corporation tax into line with that of Ireland.

Regarding the invitation to visit the site of the Battle of the Boyne, Paisley says, “We both look forward to the visit to the battle site at the Boyne… Not to refight it, because that would be unfair, for he would have the home advantage. No Ulsterman ever gives his opponents an advantage. He adds, “Such a visit would help to demonstrate how far we have come when we can celebrate and learn from the past, so the next generation more clearly understands.”

Ahern pays tribute to the leadership shown by Paisley in helping to deliver a better future for the people of Northern Ireland. As Northern Ireland’s politicians continue at great pace to prepare for the return of power sharing, the taoiseach says that the progress has been very encouraging. “At this important time in our history, we must do our best to put behind us the terrible wounds of our past and work together to build a new relationship between our two traditions,” he says. “That new relationship can only be built on a basis of open dialogue and mutual respect. I fervently believe that we move on from here in a new spirit of friendship. The future for this island has never been brighter. I believe that this is a future of peace, reconciliation and rising prosperity for all. We stand ready to work with the new executive. We promise sincere friendship and assured cooperation. I believe that we can and will work together in the interests of everyone on this island.”

Ahern says he believes that the Battle of the Boyne site can be a symbol of the new beginning in the relationship between governments in Belfast and Dublin. “I believe that this site can become a valuable and welcome expression of our shared history and a new point of departure for an island, north and south, which is at ease with itself and respectful of its past and all its traditions,” he declared.

The Battle of the Boyne was fought in 1690 between the followers of England‘s King William of Orange, a Protestant, and the deposed King James, a Catholic, in Drogheda, eastern Ireland. Ireland was at that point under English rule. The battle is commemorated by many Northern Irish loyalists on July 12 each year.

Ministerial posts within the new devolved Stormont government have yet to be finalised. Already Sinn Féin has announced that MPs Michelle Gildernew and Conor Murphy and assembly members Gerry Kelly and Caitríona Ruane will be members of the government. However, the party has not yet indicated which of the four will take the three senior cabinet posts in education, agriculture and regional development and which one will be the junior minister in the Office of First and Deputy First Minister.

The DUP has also yet to name its ministers, but it has chosen finance, economy, environment and culture arts and leisure as the government departments it will head. The DUP’s deputy leader, Peter Robinson, and Nigel Dodds, the Belfast North MP, who both served in the last devolved government, are tipped to be the finance and economy ministers.

The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) announces the previous day that Margaret Ritchie, the assembly member for South Down, will be its only minister in the executive, taking charge of the Department of Social Development.

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) has yet to declare who their two ministers will be at the Departments of Health and Employment and Learning.

(From: “Upbeat Paisley shares first handshake with Irish PM” by Hélène Mulholland and agencies, The Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com, April 4, 2007)