Sidney Sarah Madge Czira (née Gifford), journalist, broadcaster, writer and revolutionary, known by her pen name John Brennan, is born in Rathmines, Dublin, on August 3, 1889. She is an active member of the revolutionary group Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland) and writes articles for its newspaper, Bean na h-Éireann, and for Arthur Griffith‘s newspaper Sinn Féin.

Gifford is the youngest of twelve children of Frederick and Isabella Gifford. Isabella Gifford (née Burton), is a niece of the artist Frederic William Burton, and is raised with her siblings in his household after the death of her father, Robert Nathaniel Burton, a rector, during the Great Famine.

Gifford’s parents—her father is Catholic and her mother Anglican—are married in St. George’s Church, a Church of Ireland church on the north side of Dublin, on April 27, 1872. She grows up in Rathmines and is raised as a Protestant, as are her siblings.

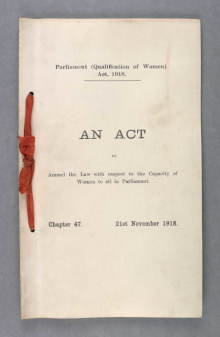

Like her sisters, the socialist Nellie Gifford, Grace Gifford, who marries Joseph Plunkett, and Muriel Gifford, who marries Thomas MacDonagh, she becomes interested and involved in the suffrage movement and the burgeoning Irish revolution.

Gifford is educated in Alexandra College in Earlsfort Terrace. After leaving school she studies music at the Leinster House School of Music. It is her music teacher, in her teens, who first gives her her first Irish national newspaper, The Leader. She begins reading this secretly and then starts reading Arthur Griffith’s newspaper, Sinn Féin.

Gifford is a member of Inghinidhe na hÉireann, a women’s political organisation active from the 1900s. It is founded by Maud Gonne and a group of working-class and middle-class women to promote Irish culture and help to alleviate the shocking poverty of Dublin and other cities at a time when Dublin’s slums are unfavourably compared with Calcutta‘s. Gifford, who is already writing under the name “John Brennan” for Sinn Féin, is asked to write for its newspaper Bean na h-Éireann. Her articles vary from those highlighting poor treatment of women in the workplace to fashion and gardening columns, some written under the pseudonym Sorcha Ní hAnlúan.

She also works, along with her sisters, in Maud Gonne’s and Constance Markievicz‘s dinner system in St. Audoen’s Church, providing good solid dinners for children in three Dublin schools – poor Dublin schoolchildren often arrive at school without breakfast, go without a meal for the day, and if their father has been given his dinner when they arrive home, might not eat or might only have a crust of bread that night.

In 1911, Gifford is elected (as John Brennan) to the executive of the political group Sinn Féin.

Gifford is a member of Cumann na mBan (The Irish Women’s Council) from its foundation in Dublin on April 2, 1914. Its members learn first aid, drilling and signalling and rifle shooting, and serve as an unofficial messenger and backup service for the Irish Volunteers. During the fight for Irish Independence the women carry messages, store and deliver guns and run safe houses where men on the run can eat, sleep and pick up supplies.

In 1914, Gifford moves to the United States to work as a journalist. Through her connection with Padraic Colum and Mary Colum, whom she had met through her brother-in-law Thomas MacDonagh, she meets influential Irish Americans such as Thomas Addis Emmet and Irish exiles like John Devoy, and marries a Hungarian lawyer, Arpad Czira, a former prisoner of war who is said to have escaped and fled to America. Their son, Finian, is born in 1922.

Czira writes both for traditional American newspapers and for Devoy’s newspaper, The Gaelic American. She and her sister Nellie found the American branch of Cumann na mBan, and she acts as its secretary. Both sisters tour and speak about the Easter Rising and those involved. She is an active campaigner for Irish independence and against the United States joining the war against Germany, seen as a war for profit and expansion of the British Empire, and so to the disadvantage of the work for Irish independence. She helps Nora Connolly O’Brien to contact German diplomats in the United States.

In 1922, Czira returns to Ireland with her son. As a member of the Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League, she is an activist against the ill-treatment of Republican prisoners during the Irish Civil War. She continues to work as a journalist, though she is stymied in her work, as are the women of her family and many of those who had taken the anti-Free State side. In the 1950s her memoirs are published in The Irish Times, and she moves into work as a broadcaster and produces a series of historical programmes.

Czira dies in Dublin on September 15, 1974, and is buried in Dean’s Grange Cemetery.