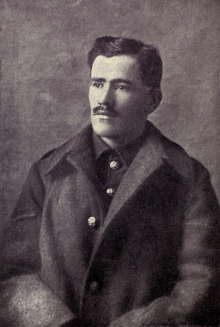

Bernardo O’Higgins, Chilean independence leader who freed Chile from Spanish rule in the Chilean War of Independence, is born on August 20, 1778, in Chillán, a town in southern Chile, then a colony of Spain.

As noted in his Certificate of Baptism, O’Higgins is the illegitimate son of Ambrosio O’Higgins, 1st Marquess of Osorno, a Spanish officer originally from County Meath who becomes Royal Governor of Chile and later viceroy of Peru. His mother is Isabel Riquelme, a prominent lady of Chillán. His father has only indirect contact with his son, who uses his maternal surname until his father’s death. At 12, he is sent to Lima for his secondary education. Four years later he goes to Spain. At 17 he is sent to England for further education. In London he becomes imbued with a sense of nationalist pride in Chile, a pride largely fostered by his contact with several political activists, of whom Francisco de Miranda, the Venezuelan champion of Latin American independence, exerts the greatest influence on him. Along with several other future revolutionary leaders, he belongs to a secret Masonic lodge, established in London by Miranda, the members of which are dedicated to the independence of Latin America. In 1799 he leaves England for Spain, where he comes into contact with Latin American clerics who also favour independence and doubtless further strengthened his views. His political position is remarkable in view of the fact that his father is viceroy of Peru.

O’Higgins’s father dies in 1801, leaving him a large hacienda near Chillán and by 1803 he is working the estate. This interlude is possibly the most satisfying period of his life. The hacienda begins to prosper almost immediately, and he is soon maintaining a house in Chillán. In 1806 he becomes a member of the local town council.

Before O’Higgins has time to settle into his agrarian way of life, however, the foundations of Chilean society are threatened. In 1808 Napoleon invades Spain, which, occupied with its own defense, leaves its colonies, including Chile, largely uncontrolled. The first steps toward national independence begin to be taken throughout Spanish America. On September 18, 1810, a national junta, composed of local leaders who replaced the governor-general, is established in Santiago, and by 1811 Chile has its own congress. O’Higgins is a member, and during the next two years he plays a key role in the country’s turbulent political affairs.

By early 1813 Chile has a constitution and a junta that seems able to control the country and to avert the threat of civil war. In 1814, however, the viceroy of Peru sponsors an expedition to reestablish royal authority. Within a few months, O’Higgins rises from the rank of colonel of militia to general in chief of the independentist forces. Soon he is also appointed governor of the province of Concepción, in which the early fighting takes place. But the war goes badly, and he is superseded in command. In October 1814, at Rancagua, the Chilean patriots led by him lose decisively to the royalist forces, which, for the next three years, occupy the country.

Several thousand Chileans, including O’Higgins, cross the Andes into Argentina in flight from the royalists. He spends the next three years preparing for the reconquest of Chile. In January 1817 he returns to Chile with the Argentine general José de San Martín and a combined army consisting of Argentine troops and Chilean exiles. At Chacabuco, on February 12, 1817, they decisively defeat the Spanish, and, with Chile largely reconquered, O’Higgins is elected interim Supreme Director.

For the next six years, as Supreme Director, O’Higgins maintains, on balance, a successful administration. He creates a working governmental organization and provides the essentials of the new nation — peace and order. Under adverse circumstances he succeeds in building a national navy and in mounting a major military expedition against Peru to fight the royalists.

O’Higgins, however, is not politically astute. By 1820 he has antagonized the conservative church and the unruly aristocracy with his reforms. Later he alienates the business community. He does not perceive the importance of a solid political base, and, because his support is based on his prestige as a war leader in a threatened country, his fall is assured once the danger of war has disappeared. He is associated with a grand scheme of continental independence that is essentially Argentine in its conception. By the time of his resignation, under pressure, in January 1823, a growing Chilean nationalism has rendered him and his Argentine colleagues much less attractive than they had been in 1817.

In 1809, at the age of 31, O’Higgins observes, “The career to which I seem inclined by instinct and character, is that of labourer.” In rural life, he would have come to be “a good campesino and a useful citizen.” As Supreme Director, he has the positive attributes of solid moral principles, an eagerness to work hard, and singular honesty. In the countryside, as he himself understands, these virtues would be ample, but in public administration they are not enough.

From 1823 until his death, O’Higgins lives in exile in Peru, dividing his time between his hacienda and Lima. His last years are poignantly similar to his first. In his youth, circumstances required that he live away from home; now in maturity, circumstances again conspire to keep him abroad. In both periods, he longs to return home.

In 1842, the National Congress of Chile finally votes to allow O’Higgins to return to Chile. After traveling to Callao to embark for Chile, however, he begins to succumb to cardiac problems and is too weak to travel. His doctor orders him to return to Lima, where on October 24, 1842, aged 64, he dies.

After his death, O’Higgins’s remains are first buried in Peru, before being repatriated to Chile in 1869. He had wished to be buried in the city of Concepción, but this is never to be. For a long time they remain in a marble coffin in the Cementerio General de Santiago, and in 1979 his remains are transferred by Augusto Pinochet to the Altar de la Patria, in front of the Palacio de La Moneda. In 2004, his body is temporarily stored at the Chilean Military School during the building of the Plaza de la Ciudadanía, before being finally laid to rest in the new underground Crypt of the Liberator.

Little is known of O’Higgins’s personal life. Though he never marries, he manages to acquire a family, in the same manner as his father had. His natural son, Pedro Demetrio O’Higgins, is his companion in exile.

O’Higgins is a liberal in the 19th-century sense of the term and an admirer of the British constitutional system. Although not as conservative as some contemporary Chilean leaders, he is not a democrat either. While his reputation since his death has fluctuated with the political predilections of governments and historians, his leading role in establishing Chile as a republic remains unquestioned.

(From: “Bernardo O’Higgins” by Jay Kinsbruner, Encyclopædia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com)