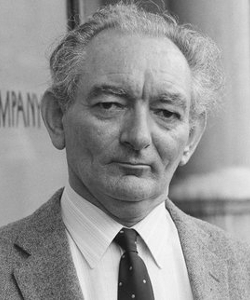

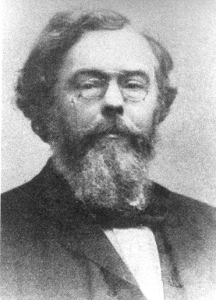

George Sigerson, Irish physician, scientist, writer, politician, and poet, is born at Holy Hill, near Strabane in County Tyrone on January 11, 1836. He is a leading light in the Irish Literary Revival of the late 19th century in Ireland.

Sigerson is the son of William and Nancy (née Neilson) Sigerson and has three brothers, James, John and William, and three sisters, Ellen, Jane, and Mary Ann. He attends Letterkenny Academy but is sent by his father, who developed the spade mill and who played an active role in the development of Artigarvan, to complete his education in France.

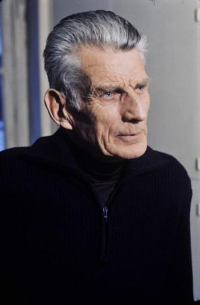

He studies medicine at the Queen’s College, Galway, and Queen’s College, Cork, and takes his degree in 1859. He then goes to Paris where he spends some time studying under Jean-Martin Charcot and Duchenne de Boulogne. Sigmund Freud is one of his fellow students.

Sigerson returns to Ireland and opens a practice in Dublin, specializing in neurology. He continues to visit France annually to study under Charcot. His patients included Maud Gonne, Austin Clarke, and Nora Barnacle. He lectures on medicine at the Catholic University of Ireland and is professor of zoology and later botany at the University College Dublin.

His first book, The Poets and Poetry of Munster, appears in 1860. He is actively involved in political journalism for many years, writing for The Nation. Sigerson and his wife Hester are by now among the dominant figures of the Gaelic Revival. They frequently hold Sunday evening salons at their Dublin home to which artists, intellectuals, and rebels alike attend, including John O’Leary, W.B. Yeats, Patrick Pearse, Roger Casement, and 1916 signatory Thomas MacDonagh. Sigerson is a co-founder of the Feis Ceoil and President of the National Literary Society from 1893 until his death. His daughter, Dora, is a poet who is also involved in the Irish literary revival.

Nominated to the first Seanad Éireann of the Irish Free State, Sigerson briefly serves as the first chairman on December 11-12, 1922, before the election of James Campbell, 1st Baron Glenavy. Sigerson dies at his home at 3 Clare Street, Dublin, on February 17, 1925, at the age of 89, after a short illness. On February 18, 1925, the day after his death, the Seanad Éireann pays tribute to him.

The Sigerson Cup, the top division of third level Gaelic football competition in Ireland is named in his honour. Sigerson donates the salary from his post at UCD so that a trophy can be purchased for the competition. In 2009, he is named in the Sunday Tribune‘s list of the “125 Most Influential People In GAA History.” The cup is first presented in 1911, with the inaugural winners being UCD GAA.