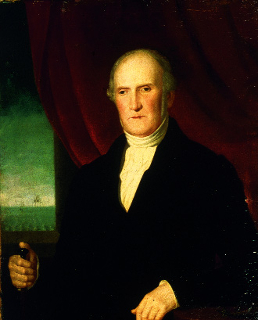

William James MacNeven, Irish American physician and writer, dies in New York City on July 12, 1841.

MacNeven is born on March 21, 1763, at Ballinahown, Aughrim, County Galway. The eldest of four sons, at the age of 12 MacNeven is sent by his uncle Baron MacNeven to receive his education abroad as the Penal Laws render education impossible for Catholics in Ireland. He makes his collegiate studies in Prague. His medical studies are made in Vienna where he is a pupil of Pestel and takes his degree in 1784. He returns to Dublin in the same year to practise.

MacNeven becomes involved in the Society of United Irishmen with such men as Lord Edward Fitzgerald, Thomas Addis Emmet, and his brother Robert Emmet. He is arrested in March 1798 and confined in Kilmainham Gaol, and afterwards in Fort George, Scotland, until 1802, when he is liberated and exiled. In 1803, he is in Paris seeking an interview with Napoleon Bonaparte in order to obtain French troops for Ireland. Disappointed in his mission, MacNeven comes to the United States, landing at New York City on July 4, 1805.

In 1807, he delivers a course of lectures on clinical medicine in the recently established College of Physicians and Surgeons. Here in 1808, he receives the appointment of professor of midwifery. In 1810, at the reorganization of the school, he becomes the professor of chemistry, and in 1816 is appointed to the chair of materia medica. In 1826 with six of his colleagues, he resigns his professorship because of a misunderstanding with the New York Board of Regents and accepts the chair of materia medica at Rutgers Medical College, a branch of the New Jersey institution of that name, established in New York as a rival to the College of Physicians and Surgeons. The school at once becomes popular because of its faculty, but after four years is closed by legislative enactment on account of interstate difficulties. The attempt to create a school independent of the regents results in a reorganization of the University of the State of New York.

MacNeven, affectionately known as “The Father of American Chemistry,” dies in New York City on July 12, 1841. He is buried on the Riker Farm in the Astoria section of Queens, New York.

One of the oldest obelisks in New York City is dedicated to him in the Trinity Church, located between Wall Street and Broadway, New York. The obelisk is opposite to another commemorated for his friend Thomas Emmet. MacNeven’s monument features a lengthy inscription in Irish, one of the oldest existent dedications of this kind in the Americas.