Northern Irish artist John Luke dies in Belfast on February 4, 1975.

Luke is born at 4 Lewis Street in Belfast on January 19, 1906, the fifth of seven sons and one daughter of James Luke and his wife Sarah, originally from Ahoghill, County Antrim. He attends the Hillman Street National School and in 1920 goes to work at the York Street Flax Spinning Company. He goes on soon after to become a riveter at the Workman, Clark shipyard. While working there he enrolls in evening classes at the Belfast School of Art.

Luke excells at the college under the tutelage of Seamus Stoupe and Newton Penpraze. His contemporaries include Romeo Toogood, Harry Cooke Knox, George MacCann and Colin Middleton. In 1927 he wins the coveted Dunville Scholarship which enables him to attend the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where he studies painting and sculpture under the celebrated Henry Tonks, who greatly influences his development as a draughtsman.

Luke remains at the Slade School of Fine Art until 1930, in which year he wins the Robert Ross Scholarship. On leaving the Slade School he stays in London, intent on establishing himself in the art world. For a time he shares a flat with fellow Ulsterman F. E. McWilliam, and enrolls as a part-time student of Walter Bayes at the Westminster School of Art to study wood engraving. He begins to exhibit his work and in October 1930 shows two paintings, Entombment and Carnival, in an exhibition of contemporary art held at Leger Galleries. The latter composition, depicting a group of masked merry-makers, is singled out by the influential critic, Paul George Konody of the Daily Mail (October 3, 1930), as “one of the most attractive features of the exhibition.” But the economic climate is deteriorating and a year later, at the end of 1933, he is driven back to Belfast by the recession. He remains in Belfast, apart from a time during World War II when he goes to Killylea, County Armagh.

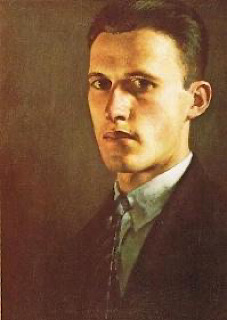

Luke paints in the style known as Regionalism, whose main proponents are Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry and Harry Epworth Allen. His painting technique is painstakingly slow, his manner precise. “I’m afraid I’m very much a one job man,” he once writes to John Hewitt, continuing, “my strength lies in making the most of one job at a time, in sustained thought and effort, to bring it to the highest level of organisation and completeness I desire: the other way I lead to disintegrate in looseness and frustration with its inevitable weakness.” The precision characteristic of his work is manifested, too, in his appearance and personal manner. Dark haired, in stature he is erect and spare of build. Always tidy, his clothes brushed, his hair short, he is, in Hewitt’s words, “not at all close to the romantic stereotype of the artist.”

Apart from Luke’s work as a practising artist, he teaches from time to time in the Belfast School of Art, where he influences a generation of students “especially in the matter of drawing,” as he once puts it. Although principally a painter, throughout his career he occasionally makes sculptures, such as the Stone Head, Seraph of c. 1940 (Ulster Museum). Indeed it is for sculpture that he wins the Robert Ross Prize at the Slade School of Fine Art. He is also much interested in philosophical theories of art. In the 1930s, for example, as John Hewitt records, topical books such as Roger Fry’s Vision and Design, Clive Bell’s Art and R. H. Wilenski‘s Modern Movement in Art direct his thinking.

From the late 1930s until 1943, when Luke produces Pax, there is a gap in his output, occasioned, no doubt, by his move to County Armagh in order to escape Belfast after the Blitz. In 1946, he holds his first one-man exhibition at the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery, and this is followed two years later by a similar show, held under the aegis of CEMA, nearby at number 55A Donegal Place. In 1950, to celebrate the Festival of Britain the following year, he is commissioned to paint in Belfast City Hall, a mural representing the history of the city, a work which brings his name to the attention of a wider audience. In later years, other commissions follow for murals in the Masonic Hall, Rosemary Street, in 1956, and the College of Technology at Millfield in the 1960s. He also carves in relief coats of arms for the two Governors of Northern Ireland, John Loder, 2nd Baron Wakehurst (1959) and John Erskine, 1st Baron Erskine of Rerrick (1965). He is also a member of the Royal Ulster Academy.

Having been in declining health for some years, Luke dies, unmarried, at the Mater Infirmorum Hospital in Belfast on February 4, 1975, just a month into his sixty-ninth year. A retrospective exhibition of his work is held, in association with the Arts Councils of Ireland, in the Ulster Museum in 1978, and is accompanied by a short monograph on his life and career written by John Hewitt. Since that time his reputation has grown enormously, his loss rekindling memories in many of his former students of a fastidiously arranged life-room in the College of Art, his coat folded to perfection and his soft, gentle manner of instruction.