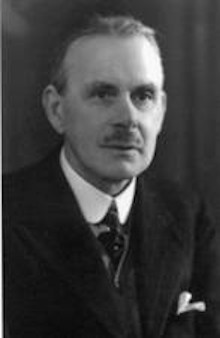

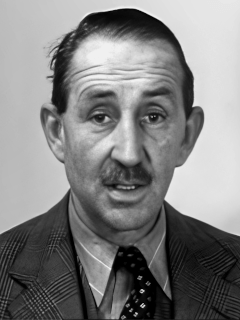

Basil Stanlake Brooke, 1st Viscount Brookeborough, KG, CBE, MC, TD, PC (Ire), Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) politician who serves as the third Prime Minister of Northern Ireland from May 1943 until March 1963, dies on August 18, 1973, at Colebrooke Park, Brookeborough, County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. He has been described as “perhaps the last Unionist leader to command respect, loyalty and affection across the social and political spectrum.” Equally well, he has also been described as one of the most hardline anti-Catholic leaders of the UUP, and his legacy involves founding his own paramilitary group, which feeds into the reactivation of the Ulster Volunteers.

Brooke is born on June 9, 1888, at Colebrooke Park, his family’s neo-Classical ancestral seat on what is then the several-thousand-acre Colebrooke Estate, just outside Brookeborough, a village near Lisnaskea in County Fermanagh. He is the eldest son of Sir Arthur Douglas Brooke, 4th Baronet, whom he succeeds as 5th Baronet when his father dies in 1907. His mother is Gertrude Isabella Batson. He is a nephew of Field Marshal Alan Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) during World War II, who is only five years his senior. His sister Sheelah marries Sir Henry Mulholland, Speaker of the Stormont House of Commons and son of Lord Dunleath. He is educated for five years at St. George’s School in Pau, France, and then at Winchester College (1901–05).

After graduating from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, Brooke is commissioned into the Royal Fusiliers on September 26, 1908, as a second lieutenant. He transfers to the 10th Royal Hussars in 1911. He is awarded the Military Cross and Croix de guerre with palm for his service during World War I.

Brooke is a very active Ulster Unionist Party member and ally of Edward Carson. He founds his own paramilitary group, Brooke’s Fermanagh Vigilance, from men returning from the war front in 1918. Although the umbrella Ulster Volunteers had been quiescent during the war, it is not defunct. It re-emerges strongly in 1920, subsuming groups like Brooke’s.

In 1920, having reached the rank of captain, Brooke leaves the British Army to farm the Colebrooke Estate, the family estate in west Ulster, at which point he turns toward a career in politics.

Brooke has a very long political career. When he resigns the Premiership of Northern Ireland in March 1963, he is Northern Ireland’s longest-serving prime minister, having held office for two months short of 20 years. He also establishes a United Kingdom record by holding government office continuously for 33 years.

In 1921, Brooke is elected to the Senate of Northern Ireland, but he resigns the following year to become Commandant of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) in their fight against the Irish Republican Army (IRA). He is created a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1921.

In 1929 Brooke is elected to the House of Commons of Northern Ireland as Ulster Unionist Party MP for the Lisnaskea division of County Fermanagh. In the words of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, “his thin, wiry frame, with the inevitable cigarette in hand, and clipped, anglicised accent were to be a feature of Stormont for the next forty years.”

Brooke becomes Minister of Agriculture in 1933. By virtue of this appointment, he also acquires the rank of Privy Councilor of Northern Ireland. From 1941 to 1943 he is Minister of Commerce.

On May 2, 1943, Brooke succeeds John M. Andrews as Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. In 1952, while Prime Minister, was raised to the peerage as Viscount Brookeborough, the title taken from the village named after the Brookes. Although a peer, he retained his seat in the House of Commons at Stormont and remained Prime Minister for another decade.

As the Northern Ireland economy begins to de-industrialise in the mid-1950s, leading to high unemployment amongst the Protestant working classes, Brooke faces increasing disenchantment amongst UUP backbenchers for what is regarded as his indifferent and ineffectual approach to mounting economic problems. As this disenchantment grows, British civil servants and some members of the UUP combine to exert discreet and ultimately effective pressure on Brooke to resign to make way for Captain Terence O’Neill, who is Minister of Finance.

In 1963, his health having worsened, Brooke resigns as Prime Minister. However, he remains a member of the House of Commons of Northern Ireland until the 1969 Northern Ireland general election, becoming the Father of the House in 1965. During his last years in the Parliament of Northern Ireland he publicly opposes the liberal policies of his successor Terence O’Neill, who actively seeks to improve relationships with the Republic of Ireland, and who attempts to address some of the grievances of Catholics and grant many of the demands of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA).

Brooke is noted for his casual style toward his ministerial duties. Terence O’Neill later writes of him, “he was good company and a good raconteur, and those who met him imagined that he was relaxing away from his desk. However, they did not realise that there was no desk.”

In his retirement Brooke develops commercial interests as chairman of Carreras (Northern Ireland), a director of Devenish Trade, and president of the Northern Ireland Institute of Directors. He is also made an honorary LL.D. of Queen’s University Belfast.

From 1970 to 1973, years in which the Stormont institution comes under its greatest strain and eventually crumbles, Brooke makes only occasional forays into political life. In 1972, he appears next to William Craig MP on the balcony of Parliament Buildings at Stormont, a diminutive figure beside the leader of the Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party (VUPP) who is rallying right-wing Unionists against the Government of Northern Ireland. He opposes the Westminster white paper on the future of Northern Ireland and causes some embarrassment to his son, Captain John Brooke, the UUP Chief Whip and an ally of Brian Faulkner, by speaking against the Faulkner ministry‘s proposals.

Brooke dies at his home, Colebrooke Park, on the Colebrooke Estate, on August 18, 1973. His remains are cremated at Roselawn Cemetery, East Belfast, three days later, and, in accordance with his wishes, his ashes are scattered on the demesne surrounding his beloved Colebrooke Park.