The Balmoral Furniture Company bombing, a paramilitary attack, takes place on December 11, 1971, in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The bomb explodes without warning outside a furniture showroom on the Shankill Road in a predominantly unionist area, killing four civilians, two of them babies.

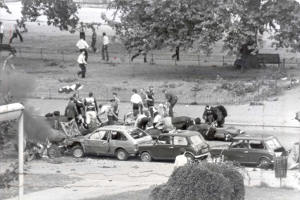

At 12:25 PM on December 11, 1971, when the Shankill Road is packed with Saturday shoppers, a green car pulls up outside the Balmoral Furniture Company at the corner of Carlow Street and Shankill Road. The shop is locally known as “Moffat’s” although Balmoral Furniture Company is its official name. One of the occupants gets out of the car and leaves a box containing a bomb on the step outside the front door. The person gets back into the car, and it speeds away. The bomb explodes moments later, bringing down most of the building on top of those inside the shop and on passersby outside.

Four people are killed as a result of the massive blast, including two babies, Tracey Munn (age 2 years) and Colin Nichol (age 17 months), who both die instantly when part of the wall crashes down upon the pram they are sharing. Two employees working inside the shop are also killed, Hugh Bruce (age 70 years) and Harold King (age 29 years). Unlike the other three victims, who are Protestant, King is a Catholic. Bruce, a former soldier and a Corps of Commissionaires member, is the shop’s doorman and is nearest to the bomb when it explodes. Nineteen people are injured in the bombing, including Tracey’s mother. The building, which was built in the Victorian era, has load-bearing walls supporting upper floors on joists. It is unable to withstand the blast and collapses, adding to the devastation and injury count.

The bombing causes bedlam in the crowded street. Hundreds of people rush to the scene where they form human chains to help the British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) free those trapped beneath the rubble by digging with their bare hands. Peter Taylor describes the scene as “reminiscent of the London Blitz” in World War II.

It is widely believed that the bombing is carried out by members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) in retaliation for the McGurk’s bar bombing one week earlier, which killed 15 Catholic civilians. The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) had carried out the McGurk’s bombing.

The Balmoral Furniture Company bombing is one of the catalysts that spark the series of tit-for-tat bombings and shootings by loyalists, republicans and the security forces that make the 1970s the bloodiest decade in the 30-year history of The Troubles.

(Pictured: Fireman is shown removing the body of one of the victims of the bombing at the Balmoral Furniture Showroom, December 11, 1971)