The Copley Street riot occurs on August 13, 1934, at the Copley Street Repository, Cork, County Cork, after Blueshirts opposed to the collection of annuities from auctioned cattle ram a truck through the gate of an ongoing cattle auction. The Broy Harriers open fire and one man, 22 year old Michael Lynch, is killed and several others injured.

Following the Irish War of Independence (1919–21), Britain relinquishes its control over much of Ireland. However, aspects of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which had marked the end of the war, lead to the Irish Civil War (1922–23). The aftermath leaves Ireland with damaged infrastructure and hinders its early development.

Éamon de Valera, who had voted against the Anglo-Irish treaty and headed the Anti-Treaty movement during the civil war, comes to power following the 1932 Irish general election and is re-elected in 1933. While the treaty stipulates that the Irish Free State should pay £3.1 million in land annuities to Great Britain, and despite advice that an economic war with Britain could have catastrophic consequences for Ireland (as 96% of exports are to Britain), de Valera’s new Irish government refuses to pay these annuities – though they continue to collect and retain them in the Irish exchequer.

This refusal leads to the Anglo-Irish trade war (also known as the “Economic War”), which persists until 1935, when a new treaty, the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement, is negotiated in 1938. During this period, a 20% duty is imposed on animals and agricultural goods, resulting in significant losses for Ireland. Specifically, poultry trade declines by 80%, butter trade by 50% and cattle prices drop by 50%. Some farmers are forced to kill and bury animals because they cannot afford to maintain them.

In 1933, Fine Gael emerges as a political party—a merger of Cumann na nGaedheal and the National Centre Party. Fine Gael garners substantial support from rural farmers who are particularly affected by the Economic War. They strongly object to the collection of land annuities by the Fianna Fáil government. The Blueshirts, a paramilitary organisation founded as the Army Comrades Association in 1932 and led by former Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy, transforms into an agrarian protest organisation, mobilising against seizures, cattle auctions, and those tasked with collecting annuities.

O’Duffy, a key figure in Irish politics, encourages farmers to withhold payment of land annuities to the government. Arising from this stance, Gardaí start to seize animals and farm equipment, auctioning them to recover the outstanding funds. While seized cattle are auctioned, local farmers rarely participate. Instead, Northern Ireland dealers, often associated with the name O’Neill, are the primary buyers. These auctions are protected by the Broy Harriers, an armed auxiliary group linked to the police.

By 1934, tensions escalate, and a series of anti-establishment incidents are attributed to the Blueshirts. These incidents range from minor acts of violence, such as breaking windows, to more serious offenses like assault and shootings.

On August 13, 1934, an auction takes place at Marsh’s Yard on Copley Street in Cork, featuring cattle seized from farms in Bishopstown and Ballincollig. The police establish a cordon by 10:00 a.m., with 300 officers on duty. Lorries arrived at 11:00 a.m.

Around noon, three thousand protestors assemble. Within twenty-five minutes, an attempt is made to breach the yard gate by ramming it with a truck. According to Oireachtas records, there are approximately 20 men in the truck which they run against the gate. The Minister for Justice P. J. Ruttledge, says that the truck “with those people in it charged through those cordons of Guards; that several Guards jumped on to the lorry and tried to divert the driver by catching hold of the steering wheel and trying to twist it.” Some contemporary news sources suggest that the ramming truck knocked down the surrounding police cordon “like ninepins and crush[ed] a police inspector against a gate.” Later sources suggest that the senior officer (a superintendent) was injured in a fall, while attempting to avoid being struck, rather than being hit directly by the truck.

A man named Michael Lynch, wearing the distinctive blue shirt, and approximately 20 others reportedly manage to enter the yard. As soon as they enter the yard they are fired upon by armed “special branch” police detectives who are in the yard. Lynch later succumbs to his injuries at the South Infirmary. Thirty-six others are wounded. Despite the violence, the auction proceeds after a one-hour delay.

Following the shooting, a riot ensues, but when news of Lynch’s death reaches the participants, they cease rioting, kneel, and recited a Rosary.

The funeral of Michael Lynch occurs on August 15, 1934. The funeral procession is planned to depart from Saints Peter and Paul’s Church, Cork at 2:30 PM.

The occasion allows for a significant show of force for Eoin O’Duffy and the Blueshirts, and features Roman salutes and military drills. Farmers in Munster reportedly stop work for an hour, and Blueshirt members ask shopkeepers to close their businesses, as a show of respect for the “martyr.” Lynch is afforded a “full Blueshirt burial,” and the coffin is adorned with the flag of the Blueshirts (the Army Comrades Association).

According to the Minister for Justice, at the funeral W. T. Cosgrave stands beside O’Duffy as the Blueshirt leader gives an oration saying, “We are going to carry on until our mission is accomplished […] those 20 brave men, whose deed will live for ever, not only in Cork but in every county in Ireland, broke through in the lorry […] all Blueshirts should try to emulate his bravery and nobleness. Every Blueshirt is prepared to go the way of Michael for his principles.”

The court grants the family £300 in 1935. This is appealed to the High Court, followed by the Supreme Court, which dismisses the case. In the Supreme Court, Henry Hanna describes the Broy Harriers as “an excrescence” upon the Garda Síochána.

When the matter is discussed in the Seanad in September 1934, and before a vote is taken to “[condemn] the action of the members of the special branch of the Gárda Síochána […] on Monday, the 13th August 1934,” the senators who support Éamon de Valera’s government walk out.

In August 1940, a memorial is unveiled on the tomb of Lynch in Dunbulloge Cemetery in Carrignavar, County Cork, consisting of a limestone Celtic cross and pedestal. The pedestal is engraved with a quote from the American orator, William Jennings Bryan: “The humblest citizen of all the land, when clad in the armour of a righteous cause is stronger than all the hosts of error.”

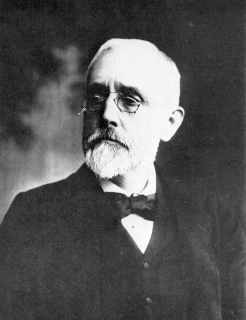

(Pictured: Aftermath of the ramming of Marsh’s Yard, Copley Street, that leads to the death of Michael Lynch and the Copley Street Riot on August 13, 1934)