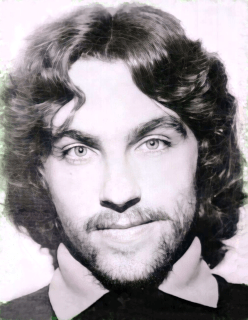

Johnny Adair, leader of “C Company” of the Ulster Loyalist paramilitary organisation Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF), a cover name of the Ulster Defence Association, is born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, on October 27, 1963. He is known as Mad Dog. He is expelled from the organisation in 2002 following a violent power struggle. Since 2003, he, his family and a number of supporters have been forced to leave Northern Ireland by other loyalists.

Adair is born into a working class loyalist background and raised in Belfast. He grows up in the Lower Oldpark area, a site of many sectarian clashes during “The Troubles.” By all accounts, he has little parental supervision, and does not attend school regularly. He takes to the streets, forming a skinhead street gang with a group of young loyalist friends, who “got involved initially in petty, then increasingly violent crime.” Eventually, he starts a rock band called Offensive Weapon, which during performances espouses support for the British National Front.

While still in his teens, Adair joins the Ulster Young Militants (UYM), and later the Ulster Defence Association, a loyalist paramilitary organisation which also calls itself the Ulster Freedom Fighters.

By the early 1990s, Adair has established himself as head of the UDA/UFF’s “C Company” based on the Shankill Road. When he is charged with terrorist offences in 1995, he admits that he had been a UDA commander for three years up to 1994. During this time, he and his colleagues are involved in multiple and random murders of Catholic civilians. At his trial in 1995, the prosecuting lawyer says he is dedicated to his cause against those whom he “regarded as militant republicans – among whom he had lumped almost the entire Roman Catholic population.” Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) detectives believe his unit killed up to 40 people during this period.

Adair once remarks to a Catholic journalist from the Republic of Ireland upon the discovery of her being Catholic, that normally Catholics travel in the boot of his car. According to a press report in 2003, he is handed details of republican suspects by British Army intelligence, and is even invited for dinner in the early 1990s. In his autobiography, he claims he was frequently passed information by sympathetic British Army members, while his own whereabouts were passed to republican paramilitaries by the RUC Special Branch, who, he claims, hated him.

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) bombing of a fish shop on the Shankill Road in October 1993 is an attempt to assassinate Adair and the rest of the UDA’s Belfast leadership in reprisal for attacks on Catholics. The IRA claims that the office above the shop is regularly used by the UDA for meetings and one is due to take place shortly after the bomb is set to explode. The bomb goes off early, killing one IRA man, Thomas Begley, and nine Protestant civilians. The UFF retaliates with a random attack on the Rising Sun bar in Greysteel, County Londonderry, which kills eight civilians, two of whom are Protestants. Adair survives 13 assassination attempts, most of which are carried out by the IRA and Irish National Liberation Army (INLA).

During this time, undercover officers from the Royal Ulster Constabulary record months of discussions with Adair, in which he boasts of his activities, producing enough evidence to charge him with directing terrorism. He is convicted and sentenced to 16 years in HM Prison Maze. In prison, according to some reports, he sells drugs such as cannabis, ecstasy tablets and amphetamines to other loyalist prisoners, earning him an income of £5000 a week.

In January 1998, Adair is one of five loyalist prisoners visited in the prison by British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Mo Mowlam. She persuades them to drop their objection to their political representatives continuing the talks that leads to the Good Friday Agreement in April. In 1999, he is released early as part of a general amnesty for political prisoners after the Agreement.

Following his release, much of Adair’s activities are bound up with violent internecine feuds within the UDA and between the UDA and other loyalist paramilitary groupings. The motivation for such violence is sometimes difficult to piece together. It involves a combination of political differences over the loyalist ceasefires, rivalry between loyalists over control of territory and competition over the proceeds of organised crime.

In 1999, shortly after his release from prison, Adair is shot at and grazed in the head by a bullet at a UB40 concert in Belfast. He blames the shooting on republicans, but it is thought that rival loyalists are to blame.

In August 2000, Adair is again mildly injured by a pipe bomb he is transporting in a car. He again attempts to blame the incident on an attack by republicans, but this claim is widely discounted. A feud breaks out at the time between the UDA and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) leaving several loyalists dead. As a result of Adair’s involvement in the violence, the then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Peter Mandelson, revokes his early release and returns him to prison.

In May 2002, Adair is released from prison again. Once free, he is a key part of an effort to forge stronger ties between the UDA/UFF and the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF), a small breakaway faction of the UVF loyalist paramilitary organization in Northern Ireland. The most open declaration of this is a joint mural depicting Adair’s UDA “C company” and the LVF. Other elements in the UDA/UFF strongly resist these movements, which they see as an attempt by Adair to win external support in a bid to take over the leadership of the UDA. Some UDA members dislike his overt association with the drugs trade, with which the LVF are even more heavily involved. A loyalist feud begins, and ends with several men dead and scores evicted from their homes.

On September 25, 2002, Adair is expelled from the UDA/UFF along with close associate John White, and the organisation almost splits as Adair tries to woo influential leaders such as Andre Shoukri, who are initially sympathetic to him. There are attempts on Adair’s and White’s lives.

Adair returns to prison in January 2003, when his early release licence is revoked by Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Paul Murphy, on grounds of engaging in unlawful activity. On February 1, 2003, UDA divisional leader John Gregg is shot dead along with another UDA member, Rab Carson, on returning from a Rangers F.C. match in Glasgow. The killing is widely blamed on Adair’s C Company as Gregg is one of those who organised his expulsion from the UDA. Five days later, on February 6, about twenty Adair supporters, including White, flee their homes for Scotland, widely seen as a response to severe intimidation.

Adair is released from prison again on January 10, 2005. He immediately leaves Northern Ireland and joins his family in Bolton, Lancashire, where it is claimed he stays with supporters of Combat 18 and the Racial Volunteer Force.

The police in Bolton question Adair’s wife, Gina, about her involvement in the drugs trade, and his son, nicknamed both “Mad Pup” and “Daft Dog,” is charged with selling crack cocaine and heroin. Adair is arrested and fined for assault and threatening behaviour in September 2005. He had married Gina Crossan, his partner for many years and the mother of his four children, at HM Prison Maze on February 21, 1997. She is three years Adair’s junior and grew up in the same Lower Oldpark neighbourhood.

After being released, Adair is almost immediately arrested again for violently assaulting Gina, who suffers from ovarian cancer. Since this episode he reportedly moves to Scotland, living in Troon in Ayrshire.

In May 2006, Adair reportedly receives £100,000 from John Blake publishers for a ghost-written autobiography.

In November 2006, the UK’s Five television channel transmits an observational documentary on Adair made by Dare Films.

Adair appears in a documentary made by Donal MacIntyre and screened in 2007. The focus of the film centers around Adair and another supposedly reformed character, a Neo-Nazi from Germany called Nick Greger, and their trip to Uganda to build an orphanage. Adair is seen to fire rifles, stating it is the first time he has done so without wearing gloves. He also admits to being “worried sick” and “pure sick with worry” after Greger disappears in Uganda for days on end. It turns out that he had gone off and married a Ugandan lady. Adair confesses via telephone that he “thought something might have happened to Nick.”

On July 20, 2015, three Irish republicans, Antoin Duffy, Martin Hughes and Paul Sands, are found guilty of planning to murder Adair and Sam McCrory. Charges against one of the accused in the trial are dropped on July 1.

On September 10, 2016, Adair’s son, Jonathan Jr., is found dead in Troon, aged 32. He dies from an accidental overdose while celebrating the day after his release from prison for motoring offences. He had been in and out of prison since the family fled Northern Ireland. He served a five-year sentence for dealing heroin and crack cocaine. The year before, he had been cleared of a gun raid at a party and in 2012 is the target of a failed bomb plot. He was also facing trial later that year on drugs charges.

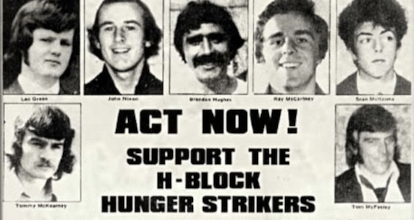

In December 2023, while recording a podcast with far-right activist Tommy Robinson, Adair surprisingly expresses a grudging respect for the IRA hunger strikers, describing the manner of their deaths as “dedication at the highest level” for a political cause and admitting that he would not have volunteered to do the same if asked.