The Irish National Land League, one of the most important political organizations in Irish history which seeks to help poor tenant farmers, is founded at the Imperial Hotel in Castlebar, County Mayo, on October 21, 1879. Its primary aim is to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmers to own the land they work on. The national organization is modeled on the Land League of Mayo, which Michael Davitt had helped found earlier in the year.

At the founding meeting Charles Stewart Parnell is elected president of the league. Davitt, Andrew Kettle, and Thomas Brennan are appointed as honorary secretaries. This unites practically all the different strands of land agitation and tenant rights movements under a single organisation.

Parnell, Davitt, John Dillon, and others including Cal Lynn then go to the United States to raise funds for the League with spectacular results. Branches are also set up in Scotland, where the Crofters Party imitates the League and secures a reforming Act in 1886.

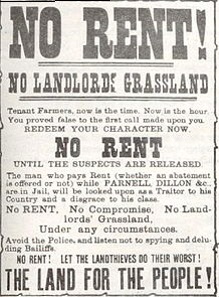

The government introduces the Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act 1870, which proves largely ineffective. It is followed by the marginally more effective Land Acts of 1880 and 1881. These establish a Land Commission that starts to reduce some rents. Parnell together with all of his party lieutenants including Father Eugene Sheehy, known as “the Land League priest,” go into a bitter verbal offensive and are imprisoned in October 1881 under the Protection of Person and Property Act 1881 in Kilmainham Gaol for “sabotaging the Land Act.” It is from here that the No-Rent Manifesto is issued, calling for a national tenant farmer rent strike until “constitutional liberties” are restored and the prisoners freed. It has a modest success In Ireland and mobilizes financial and political support from the Irish Diaspora.

Although the League discourages violence, agrarian crimes increase widely. Typically, a rent strike is followed by eviction by the police and the bailiffs. Tenants who continue to pay the rent can be subject to a boycott by local League members. Where cases go to court, witnesses would change their stories, resulting in an unworkable legal system. This in turn leads on to stronger criminal laws being passed that are described by the League as “Coercion Acts.”

The bitterness that develops helps Parnell later in his Home Rule campaign. Davitt’s views as seen in his famous slogan: “The land of Ireland for the people of Ireland” is aimed at strengthening the hold on the land by the peasant Irish at the expense of the alien landowners. Parnell aims to harness the emotive element, but he and his party are strictly constitutional. He envisions tenant farmers as potential freeholders of the land they have rented.