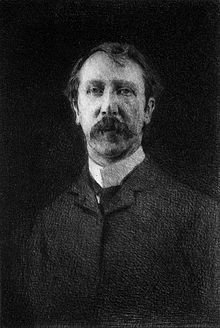

John “Jack” Butler Yeats, artist, Olympic medalist and brother of William Butler Yeats, dies in Dublin on March 28, 1957.

Butler’s early style is that of an illustrator. He only begins to work regularly in oils in 1906. His early pictures are simple lyrical depictions of landscapes and figures, predominantly from the west of Ireland, especially of his boyhood home of Sligo. His work contains elements of Romanticism.

Yeats is born in London on August 29, 1871. He is the youngest son of Irish portraitist John Butler Yeats. He grows up in Sligo with his maternal grandparents, before returning to his parents’ home in London in 1887. Early in his career he works as an illustrator for magazines like The Boy’s Own Paper and Judy, draws comic strips, including the Sherlock Holmes parody “Chubb-Lock Homes” for Comic Cuts, and writes articles for Punch under the pseudonym “W. Bird.” In 1894 he marries Mary Cottenham, also a native of England and two years his senior and resides in Wicklow according to the Census of Ireland, 1911.

From around 1920, Yeats develops into an intensely Expressionist artist, moving from illustration to Symbolism. He is sympathetic to the Irish Republican cause, but not politically active. However, he believes that “a painter must be part of the land and of the life he paints,” and his own artistic development, as a Modernist and Expressionist, helps articulate a modern Dublin of the 20th century, partly by depicting specifically Irish subjects, but also by doing so in the light of universal themes such as the loneliness of the individual, and the universality of the plight of man. Samuel Beckett writes that “Yeats is with the great of our time… because he brings light, as only the great dare to bring light, to the issueless predicament of existence.” The Marxist art critic and author John Berger also pays tribute to Yeats from a very different perspective, praising the artist as a “great painter” with a “sense of the future, an awareness of the possibility of a world other than the one we know.”

Yeats’s favourite subjects include the Irish landscape, horses, circus and travelling players. His early paintings and drawings are distinguished by an energetic simplicity of line and colour, his later paintings by an extremely vigorous and experimental treatment of often thickly applied paint. He frequently abandons the brush altogether, applying paint in a variety of different ways, and is deeply interested in the expressive power of colour. Despite his position as the most important Irish artist of the 20th century, he takes no pupils and allows no one to watch him work, so he remains a unique figure. The artist closest to him in style is his friend, the Austrian painter, Oskar Kokoschka.

Besides painting, Yeats has a significant interest in theatre and in literature. He is a close friend of Samuel Beckett. He designs sets for the Abbey Theatre, and three of his own plays are also produced there. He writes novels in a stream of consciousness style that James Joyce acknowledges, and also many essays. His literary works include The Careless Flower, The Amaranthers, Ah Well, A Romance in Perpetuity, And To You Also, and The Charmed Life. His paintings usually bear poetic and evocative titles. He is elected a member of the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1916.

Yeats holds the distinction of being Ireland’s first medalist at the Olympic Games in the wake of creation of the Irish Free State. At the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, his painting The Liffey Swim wins a silver medal in the arts and culture segment of the Games. In the competition records the painting is simply entitled Swimming.

Yeats dies in Dublin on March 28, 1957, and is buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery.