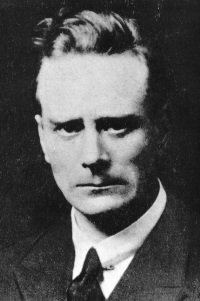

Rory O’Connor, Irish republican revolutionary, is executed by firing squad on December 8, 1922, in reprisal for the anti-treaty Irish Republican Army‘s (IRA) killing of Irish Free State member of parliament Sean Hales.

O’Connor is born in Kildare Street, Dublin on November 28, 1883. He is educated at St. Mary’s College, Dublin and then in Clongowes Wood College, a public school run by the Jesuit order and also attended by James Joyce, and his close friend Kevin O’Higgins, the man who later condemns him to death.

In 1910 O’Connor takes his Bachelor of Engineering and Bachelor of Arts degrees in University College Dublin, then known as the National University. He goes to work as a railway engineer in Ireland, then moves to Canada, where he is an engineer in the Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian Northern Railway, being responsible for the construction of 1,500 miles of railroad.

After his return to Ireland, O’Connor becomes involved in Irish nationalist politics, joins the Ancient Order of Hibernians and is interned after the Easter Rising in 1916.

During the subsequent Irish War of Independence (1919-1921) O’Connor is made Director of Engineering of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) – a military organisation descended from the Irish Volunteers.

O’Connor does not accept the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which establishes the Irish Free State and abolishes the Irish Republic declared in 1916, which he and his comrades had sworn to uphold. On March 26, 1922, the anti-treaty officers of the IRA hold a convention in Dublin in which they reject the Treaty compromise and repudiate the authority of the Dáil, the elected Irish Parliament. Asked by a journalist if this means they are proposing a military dictatorship in Ireland, O’Connor replies, “you can take it that way if you want.”

On April 14, 1922, O’Connor, with 200 other hardline anti-treaty IRA men under his command, takes over the Four Courts building in the centre of Dublin in defiance of the new Irish government. They want to provoke the British troops, who are still in the country, into attacking them, which they believe will restart the war with Britain and re-unite the IRA against their common enemy. Michael Collins tries desperately to persuade O’Connor and his men to leave the building before fighting breaks out.

On June 28, 1922, after the Four Courts garrison has kidnapped JJ “Ginger” O’Connell, a general in the new Free State Army, Collins shells the Four Courts with borrowed British artillery. O’Connor surrenders after two days of fighting and is arrested and held in Mountjoy Prison. This incident sparks the Irish Civil War as fighting breaks out around the country between pro and anti-treaty factions.

On December 8, 1922, along with Liam Mellows, Richard Barrett and Joe McKelvey, three other republicans captured with the fall of the Four Courts, Rory O’Connor is executed by firing squad in reprisal for the anti-treaty IRA’s killing of Free State member of parliament Sean Hales. The execution order is given by Kevin O’Higgins, who less than a year earlier had appointed O’Connor to be best man at his wedding, symbolising the bitterness of the division that the Treaty has caused. O’Connor, one of 77 republicans executed by the Cumann na nGaedheal government of the Irish Free State, is seen as a martyr by the Republican movement in Ireland.