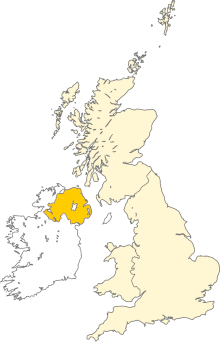

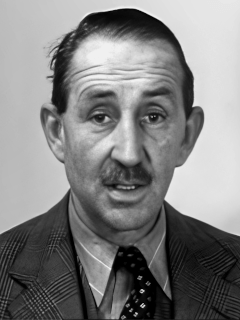

James Dawson Chichester-Clark, Baron Moyola, the penultimate Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and eighth leader of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), is born as James Dawson Clark on February 12, 1923, at Moyola Park, near Castledawson, County Londonderry, his family’s ancestral home.

Chichester-Clark is the eldest of three children of James Lenox-Conyngham Clark and Marion Caroline Dehra (née Chichester). His brother is Robin Chichester-Clark and his sister is Penelope Hobhouse, the garden writer and historian.

In 1924, James Clark Snr. changes the family name to Chichester-Clark by deed poll, thus preventing the old Protestant Ascendancy name Chichester, his wife’s maiden name, from dying out. On his mother’s side the family are descended from the Donegall Chichesters and are the heirs of the Dawsons of Castledawson, who had originally held Moyola Park.

Educated, against his own wishes, at Selwyn House, Broadstairs, and then Eton College, Chichester-Clark leaves school and enters adulthood in the midst of World War II. On joining the Irish Guards, the regiment of his grandfather, in Omagh, he begins his year-long training at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, before receiving his commission as a second lieutenant.

Chichester-Clark marries widow Moyra Haughton (née Morris) in 1959. Lady Moyola’s first husband, Capt. Thomas Haughton from Cullybackey, had been killed in the RAF Nutts Corner air crash in January 1953. She, while pregnant, is seriously injured in the crash and suffers a broken neck. He and his wife have two daughters (Tara and Fiona), in addition to Moyra’s son Michael from her previous marriage. Lady Moyola is a cousin of Colonel Sir Michael McCorkell, Lord Lieutenant of County Londonderry (1975–2000). Chichester-Clark serves as his Vice Lord-Lieutenant.

Chichester-Clark is an officer in the 1st Battalion, Irish Guards, part of 24th Infantry Brigade attached to British 1st Infantry Division, and participates briefly in the Anzio landings. He is injured on February 23, 1944, by an 88m shell as he and his Platoon Sergeant take their first look at the ground in the “gullies” to the west of the Anzio–Albano Laziale road. His company is all but wiped out, and he spends most of the war in hospital recovering from injuries, the effects of which stay with him throughout his life.

Following the war, Chichester-Clark’s military career takes him from the dull duties of the post-war occupation of Germany, to Canada as aide-de-camp to Harold Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Tunis, then Governor General of Canada. The popularity and competence of his senior officer makes this uneventful two-year period of his life the most remarkable element of his pre-parliamentary career. On returning from Canada, he continues in the Army for several years, refusing promotion to seniority before retiring a major in 1960.

In an uncontested by-election in 1960, Chichester-Clark takes over the South Londonderry seat in the Northern Ireland Parliament that had been held by his grandmother, Dame Dehra Parker, since 1933. As Dehra Chichester, she is an MP for the county of Londonderry until 1929 when she stands down for a first time. Chichester-Clark’s father replaces her in 1929 when the county is split, but he suddenly dies in 1933. Dehra, by then remarried, willingly returns to Northern Ireland from England, and wins the ensuing by-election.

Chichester-Clark retains the seat for the remainder of the Parliament’s existence, and so the South Londonderry area is represented by three generations of the same family for the entire period of the Northern Ireland House of Commons. Between 1929 and the last election in 1969, the family is challenged for the seat on only two occasions, the second being in 1969, when future Westminster MP Bernadette Devlin stands, attracting 39% of the vote.

Chichester-Clark makes his maiden speech on February 8, 1961, during the Queen’s speech debate.

For the remainder of Basil Brooke, 1st Viscount Brookeborough‘s premiership, Chichester-Clark remains on the back benches. It is not until 1963, when Terence O’Neill becomes Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, that he is appointed assistant whip, and a month later when William Craig is promoted to the Ministry of Home Affairs, he takes over as Government Chief Whip. Accounts of the period are that he enjoys the Whip’s office more than any other he is to subsequently hold in politics. This despite including references to anti O’Neill MP and future Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) Westminster MP, John McQuade, and the occasional “good row.” From the outset, O’Neill takes the unusual decision to allow Chichester-Clark to attend and speak at all cabinet meetings while Chief Whip. Proving a competent parliamentary party administrator, O’Neill adds Leader of the House of Commons to Chichester-Clark’s duties in October 1966, a promotion that makes him a full member of the Cabinet. He is also sworn into the Privy Council of Northern Ireland in 1966.

In 1967, O’Neill sacks his Minister of Agriculture, Harry West, for ministerial impropriety, and Chichester-Clark is appointed in his place, a position he retains for two quiet years. On April 23, 1969, he resigns from the Cabinet one day prior to a crucial Parliamentary Party meeting, claiming that he disagrees with the Prime Minister’s decision to grant universal suffrage in local government elections at that time. He states that he disagrees not with the principle of one man one vote but with the timing of the decision, having the previous day expressed doubts over the expediency of the measure in Cabinet. It has since been suggested that his resignation was in order to accelerate O’Neill’s own resignation, and to improve his own position in the jostling to succeed him.

O’Neill “finally walked away” five days later on April 28, 1969. In order to beat his only serious rival, Brian Faulkner, Chichester-Clark needs the backing of O’Neill-ite MPs elected at the 1969 Northern Ireland general election, to which end he attends a tea party in O’Neill’s honour only days after causing his resignation.

Chichester-Clark beats Faulkner in the 1969 Ulster Unionist Party leadership election by one vote on May 1, 1969, with his predecessor using his casting vote in the tied election for his distant cousin because “Faulkner had been stabbing him in the back for a lot longer.” Although Faulkner believes, until his death, that he is the victim of an upper-class conspiracy to deny him the premiership, he becomes a high profile and loyal member of Chichester-Clark’s cabinet.

Chichester-Clark’s premiership is punctuated by civil unrest that erupts after August 1969. He suffers from the effects of the Hunt Report, which recommends the disbandment of the Ulster Special Constabulary, which his Government accepts to the consternation of many Unionists.

In April 1970, Chichester-Clark’s predecessor and another Unionist MP resign their seats in the Northern Ireland House of Commons. The by-election campaigns are punctuated by major liberal speeches by senior government figures like Brian Faulkner, Jack Andrews and the Prime Minister himself. Ian Paisley‘s Protestant Unionist Party (PUP), however, takes both seats in the House of Commons. Later that same month the O’Neill-ite group, the New Ulster Movement, becomes the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland, and his party begins passing votes of no confidence in him.

As the civil unrest grows, the British Government, particularly the Home Secretary, James Callaghan, becomes increasingly involved in Northern Ireland’s affairs, forcing Chichester-Clark’s hand on many issues. These include the disbanding of the “B” Specials of the Ulster Special Constabulary and, importantly, the handing over of operational control of the security forces to the British Army General Officer Commanding Northern Ireland.

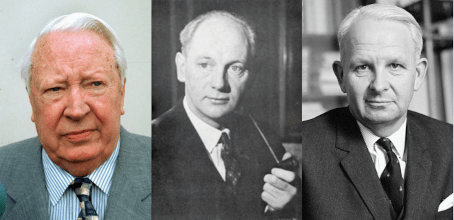

On March 9, 1971, the Provisional Irish Republican Army lures three off-duty soldiers from a pub in Belfast to a lane way outside the city, where they kill them. Chichester-Clark flies to London on March 18, 1971, to request a new security initiative from the new British prime minister Edward Heath, who offers an extra 1,300 troops, and resists what he sees as an attempt by Chichester-Clark to gain political control over them. Chichester-Clark resigns on March 20.

On March 23, 1971, Brian Faulkner is elected UUP leader in a vote by Unionist MP’s, defeating William Craig by twenty-six votes to four. He is appointed prime minister the same day.

On July 20, 1971, Chichester-Clark is created a life peer as Baron Moyola, of Castledawson in the County of Londonderry, his title taken from the name of his family’s estate. He endorses the Good Friday Agreement in the 1998 Northern Ireland Good Friday Agreement referendum. He remains quiet about his political career in his retirement. Lady Moyola, however, says that her husband does enjoy the time – contrary to popular opinion – and that he thinks of life as an MP as akin to that of an army welfare officer.

Chichester Clark dies on May 17, 2002, at the age of 79, following a short illness. His funeral takes place at Christ Church in Castledawson on May 21. He is the last surviving Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.