John Morrissey, Irish American politician, bare-knuckle boxing champion and criminal also known as ‘Old Smoke,’ is born on February 12, 1831, at Templemore, County Tipperary.

Morrissey is the only son among eight children of Timothy Morrissey, factory worker, and Julia (or Mary) Morrissey. In 1834 the family emigrates to Canada and then the United States, settling at Troy, New York. From the age of ten he works, first in a mill, and then as an iron worker due to his size and strength. He becomes involved in various street gangs, developing a reputation as a pugilist of great strength and resolve. As leader of the Down-Town gang, he defeats six members of the rival Up-Town gang in a single afternoon in 1848. He takes work on a Hudson River steamer and marries Sarah Smith, daughter of the ship’s captain, around 1849. They have one child who dies before reaching adulthood.

In a New York saloon Morrissey challenges Charley ‘Dutch’ Duane to a prize fight and, when he is not to be found, with typical bravado he extends the challenge to everyone present. This impresses the owner, Isaiah Rynders, the Tammany Hall politician, and he employs Morrissey to help the Democratic Party, which involves intimidating voters at election time. A fistfight with gang rival Tom McCann earns him the nickname ‘Old Smoke.’ Mid-fight he is forced onto a bed of coals, but despite having his flesh burned, refuses to concede defeat. He fights his way back and beats McCann into unconsciousness. Stowing away to California to challenge other fighters, he begins a gambling house to raise money and embarks on a privateering expedition to the Queen Charlotte Islands in a quixotic attempt to make his fortune.

In his first professional prize fight on August 21, 1852, Morrissey defeats George Thompson at Mare Island, California, in dubious circumstances, and begins calling himself the ‘champion of America.’ However, it is only on October 12, 1853, that he officially earns this title, when he wins the heavyweight championship of America in a bout at Boston Corner, New York, against Yankee Sullivan. The fight lasts thirty-seven rounds, and Morrissey has the worst of most of them, but he is awarded the contest after a free-for-all in the ring.

Increasingly involved in New York politics, Morrissey and his supporters fight street battles against the rival gang of William Poole, known as ‘Bill the Butcher,’ a Know Nothing politician later fictionalised in the film Gangs of New York (2002). On July 26, 1854, the two men fight on the docks, but Morrissey is beaten badly and forced to surrender. This marks the beginning of a bitter feud between the two parties, with heavy casualties on both sides, which climaxes on March 8, 1855, when Poole is murdered. Morrissey is indicted as a conspirator in the crime but is soon released because of his political connections.

On October 20, 1858, Morrissey fights John C. Heenan (1835–73) in another heavyweight championship bout. Heenan breaks his hand early in the fight and is always at a disadvantage. After taking much punishment Morrissey finally makes his dominance count. There is a rematch on April 4, 1859, which Morrissey again wins, and after this he retires from the ring. Investing his prize money, he runs two saloons and a gambling house in New York. With the huge profits from his gambling empire, he invests in real estate in Saratoga Springs, New York, opening the Saratoga Race Course there in 1863 which has endured to become America’s oldest major sports venue.

A political career beckons as a reward for Morrissey’s consistent support for the Democratic Party. He is elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1866 representing New York’s fifth district, is re-elected the following year, and serves until March 3, 1871. He supports President Andrew Johnson against demands for his impeachment and is skeptical about the Radicals’ plans for reconstruction in the south. In his final years he serves in the New York State Senate (1875–78).

After contracting pneumonia, Morrissey dies at the Adelphi Hotel, Saratoga Springs, on May 1, 1878, and is buried at Saint Peter’s Cemetery, Troy. On the day of his funeral, flags at New York City Hall are lowered to half-mast, while the National Police Gazette declares on May 4, 1878, that “few men of our day have arisen from beginnings so discouraging to a place so high in the general esteem of the community.” His name is included in the list of ‘pioneer’ inductees in the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York, and each year the John Morrissey Stakes are held at Saratoga Race Course in honour of its founder.

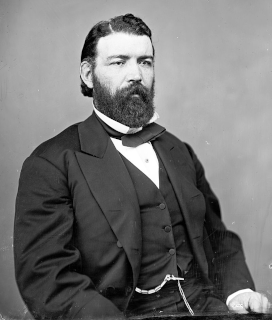

(Pictured: John Morrissey, U.S. Representative from New York, circa 1870s, source Library of Congress)