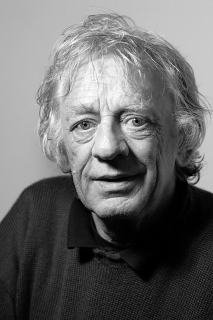

Brendan Gleeson, Irish actor and film director, is born in Dublin on March 29, 1955. He is the recipient of three Irish Film & Television Academy (IFTA) Awards, two British Independent Film Awards (BIFA), and a Primetime Emmy Award and has been nominated twice for a BAFTA Award, five times for a Golden Globe Award and once for an Academy Award. In 2020, he is listed at number 18 on The Irish Times list of Ireland’s greatest film actors. He is the father of actors Domhnall Gleeson and Brian Gleeson.

Gleeson is the son of Frank and Pat Gleeson. He has described himself as having been an avid reader as a child. He receives his second-level education at St. Joseph’s CBS in Fairview, Dublin, where he is a member of the school drama group. He receives his Bachelor of Arts at University College Dublin (UCD), majoring in English and Irish. After training as an actor, he works for several years as a secondary school teacher of Irish and English at the now defunct Catholic Belcamp College in north County Dublin. He works simultaneously as an actor while teaching, doing semi-professional and professional productions in Dublin and surrounding areas. He leaves the teaching profession to commit full-time to acting in 1991. In an NPR interview to promote Calvary in 2014, he states he was molested as a child by a Christian Brother in primary school but was in “no way traumatised by the incident.”

As a member of the Dublin-based Passion Machine Theatre company, Gleeson appears in several of the theatre company’s early and highly successful plays such as Brownbread (1987), written by Roddy Doyle and directed by Paul Mercier, Wasters (1985) and Home (1988), written and directed by Paul Mercier. He also writes three plays for Passion Machine: The Birdtable (1987) and Breaking Up (1988), both of which he directs, and Babies and Bathwater (1994) in which he acts. Among his other Dublin theatre work are Patrick Süskind‘s one-man play The Double Bass and John B. Keane‘s The Year of the Hiker.

Gleeson starts his film career at the age of 34. He first comes to prominence in Ireland for his role as Michael Collins in The Treaty, a television film broadcast on RTÉ One, and for which he wins a Jacob’s Award in 1992. He acts in such films as Braveheart, I Went Down, Michael Collins, Gangs of New York, Cold Mountain, 28 Days Later, Troy, Kingdom of Heaven, Lake Placid, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Mission: Impossible 2, and The Village. He wins critical acclaim for his performance as Irish gangster Martin Cahill in John Boorman‘s 1998 film The General.

In 2003, Gleeson is the voice of Hugh the Miller in an episode of the Channel 4 animated series Wilde Stories. While he portrays Irish statesman Michael Collins in The Treaty, he later portrays Collins’ close collaborator Liam Tobin in the film Michael Collins with Liam Neeson taking the role of Collins. He later goes on to portray Winston Churchill in Into the Storm, winning a Primetime Emmy Award for his performance. He plays Barty Crouch, Jr. impersonating Hogwarts professor Alastor “Mad-Eye” Moody in the fourth, and Alastor Moody himself in fifth and seventh Harry Potter films. His son Domhnall plays Bill Weasley in the seventh and eighth films.

Gleeson provides the voice of Abbot Cellach in The Secret of Kells, an animated film co-directed by Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey of Cartoon Saloon, which premieres in February 2009 at the Jameson Dublin International Film Festival. He stars in the short film Six Shooter in 2006, written and directed by Martin McDonagh, which wins an Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film. In 2008, he stars in the comedy crime film In Bruges, also written and directed by McDonagh. The film, and his performance, enjoy huge critical acclaim, earning him several award nominations, including his first Golden Globe nomination. In the movie, he plays a mentor-like figure for Colin Farrell‘s hitman. In his review of In Bruges, Roger Ebert describes the elder Gleeson as having a “noble shambles of a face and the heft of a boxer gone to seed.”

In July 2012, Gleeson starts filming The Grand Seduction, with Taylor Kitsch, a remake of Jean-François Pouliot‘s French-Canadian La Grande Séduction (2003) directed by Don McKellar. The film is released in 2013. In 2016, he appears in the video game adaptation Assassin’s Creed and Ben Affleck‘s crime drama Live by Night. In 2017, he finishes Psychic, a short in which he directs and stars. From 2017 to 2019 he stars in the crime series Mr. Mercedes. He receives a Golden Globe Award nomination for his performance as Donald Trump in the Showtime series The Comey Rule (2020). In 2022, he reunites with Martin McDonagh in the tragic comedy The Banshees of Inisherin starring opposite Colin Farrell. For his performance as Colm Doherty, he receives numerous awards nominations, including the Academy Award, Golden Globe, and Critics’ Choice Movie Award for Best Supporting Actor. He receives an Emmy Award nomination for Stephen Frears‘s Sundance TV series State of the Union (2022).

Gleeson is a fiddle and mandolin player, with an interest in Irish folklore. He plays the fiddle during his roles in Cold Mountain, Michael Collins, The Grand Seduction, and The Banshees of Inisherin, and also features on Altan‘s 2009 live album. In the Coen brothers‘ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018), he sings “The Unfortunate Rake.” He also makes a contribution in 2019 to the album by Irish folk group Dervish with a version of “Rocky Road to Dublin.”

Gleeson has been married to Mary Weldon since 1982. They have four sons: Domhnall, Fergus, Brían, and Rory. Domhnall and Brían are also actors. He speaks fluent Irish and is an advocate of the promotion of the Irish language. He is a fan of the English football club Aston Villa, as is his son Domhnall.