Bloody Sunday or Belfast’s Bloody Sunday is a day of violence in Belfast, Ireland (present-day Northern Ireland) on July 10, 1921, during the Irish War of Independence.

Belfast sees almost 500 people die in political violence between 1920 and 1922. Violence in the city breaks out in the summer of 1920 in response to the Irish Republican Army (IRA) killing of Royal Irish Constabulary Detective Oswald Swanzy after Sunday services outside a Protestant church in nearby Lisburn. Seven thousand Catholics and some Protestant trade unionists are driven from their jobs in the Belfast shipyards and over 50 people are killed in rioting between Catholics and Protestants.

Violence in Belfast wanes until the following summer of 1921. At the time, Irish republican and British authorities are negotiating a truce to end the war but fighting flares up in Belfast. On June 10, an IRA gunman, Jack Donaghy, ambushes three RIC constables on the Falls Road, fatally wounding one, Thomas Conlon, a Roman Catholic from County Roscommon, who, ironically, is viewed as “sympathetic” to the local nationalists. Over the following three days, at least 14 people lose their lives and 14 are wounded in fighting in the city, including three Catholics who are taken from their homes and killed by uniformed police.

Low-level attacks continue in the city over the next month until another major outbreak of violence that leads to “Bloody Sunday.” On July 8, the RIC attempt to carry out searches in the mainly Catholic and republican enclave around Union Street and Stanhope Street. However, they are confronted by about fifteen IRA volunteers in an hour-long firefight.

On July 9, a truce to suspend the war is agreed in Dublin between representatives of the Irish Republic and the British government, to come into effect at noon on July 11. Many Protestants/unionists condemn the truce as a “sell-out” to republicans.

On the night of July 9/10, hours after the truce is announced, the RIC attempt to launch a raid in the Lower Falls district of west Belfast. Scouts alert the IRA of the raid by blowing whistles, banging dustbin lids and flashing a red light. On Raglan Street, a unit of about fourteen IRA volunteers ambush an armoured police truck, killing one officer and wounding at least two others.

This sparks an outbreak of ferocious fighting between Catholics and Protestants in west Belfast the following day, Sunday July 10, in which 16 civilians lose their lives and up to 200 houses are destroyed. Of the houses destroyed, 150 are owned by Catholics. Most of the dead are civilians and at least four of the Catholic victims are ex-World War I servicemen.

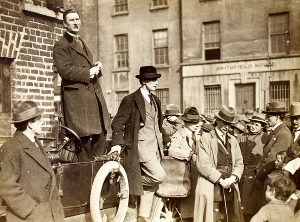

Protestants, fearful of absorption into a Catholic Ireland and blindly angered by the presence of heresy and treason in their midst, strike at the Catholic community while vengeful Catholics strike back with counter-terror. Gun battles rage all day along the sectarian “boundary” between the Catholic Falls and Protestant Shankill districts and rival gunmen use rifles, machine guns and grenades in the clashes. Gunmen are seen firing from windows, rooftops and street corners. A loyalist mob, several thousand strong, attempt to storm the Falls district, carrying petrol and other flammable materials.

A tram travelling from the Falls into the city centre is struck by snipers’ bullets, and the service has to be suspended. Catholics and republicans claim that police, mostly from the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), drive through Catholic enclaves in armoured cars firing indiscriminately at houses and bystanders. The police return to their barracks late on Sunday night, allegedly after a ceasefire has been agreed by telephone between a senior RIC officer and the commander of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, Roger McCorley.

The truce is due to come into effect at midday on Monday, July 11, but violence resumes that morning. Three people are shot dead that day, including an IRA volunteer who is shot minutes before midday. In the north the official truce does not end the fighting. While the IRA is involved in the violence, it does not control the actions of the Catholic community. Tuesday July 12 sees the Orange Order‘s annual Twelfth marches pass off peacefully and there are no serious disturbances in the city. However, sporadic violence resumes on Wednesday, and by the end of the week 28 people in all have been killed or fatally wounded in Belfast.

The violence of the period in Belfast is cyclical, and the events of July 1921 are followed by a lull until a three-day period beginning on August 29, when another 20 lives are lost in the west and north of the city. The conflict in Belfast between the IRA and Crown forces and between Catholics and Protestants continues until the following summer, when the northern IRA is left isolated by the outbreak of the Irish Civil War in the south and weakened by the rigorous enforcement of internment in Northern Ireland.

At the time the day is referred to as “Belfast’s Bloody Sunday.” However, the title of “Bloody Sunday” is now more commonly given in Ireland to events in Dublin in November 1920 or Derry in January 1972.

Members of

Members of

On February 8, 1923, the

On February 8, 1923, the