Stephen Fuller, Fianna Fáil politician who serves as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Kerry North constituency from 1937 to 1943, dies on February 23, 1984, in Tralee, County Kerry.

Fuller is born on January 1, 1900, in Kilflynn, County Kerry. He is the son of Daniel Fuller and Ellie Quinlan. His family is from Fahavane, in the parish of Kilflynn.

Fuller serves in the Kilflynn Irish Republican Army (IRA) flying column during the Irish War of Independence. He is First Lieutenant in the Kerry No.1 Brigade, 2nd Battalion. He opposes the Anglo-Irish Treaty and continues to fight with the anti-Treaty IRA during the Irish Civil War. Military records from the 1930s show, in his own hand, that he is in communication with Dublin regarding confirmation of membership in July 1922 and therefore eligible for war pensions. He becomes the most senior Kilflynn member upon the death of Captain George O’Shea.

In 1923, Fuller is captured by Free State troops and imprisoned in Ballymullen Barracks in Tralee by the Dublin Guard who had landed in County Kerry shortly before. On March 6, 1923, five Free State soldiers are blown up by a booby-trapped bomb at Baranarigh Wood, Knocknagoshel, north Kerry, including long-standing colleagues of Major General Paddy Daly, GOC Kerry Command. Prisoners receive beatings after the killings and Daly orders that republican prisoners be used to remove mines.

On March 7, nine prisoners from Ballymullen Barracks, six from the jail and three from the workhouse, are chosen with a broad geographical provenance and no well-known connections. They are taken lying down in a lorry to Ballyseedy Cross. There they are secured by the hands and legs and to each other in a circle around a land mine. Fuller is among them. His Kilflynn parish comrade Tim Tuomey is initially stopped from praying until all prisoners are tied up. As he and other prisoners then say their prayers and goodbyes, Fuller continues to watch the retreating Dublin Guard soldiers, an act which he later says saved him. The mine is detonated, and he lands in a ditch, suffering burns and scars. He crosses the River Lee and hides in Ballyseedy woods. He is missed amongst the carnage as disabled survivors are bombed and shot dead with automatic fire. Most collected body parts are distributed between nine coffins that had been prepared. The explosions and gunfire are witnessed by Rita O’Donnell who lives nearby and who sees human remains spread about the next day. Similar reprisal killings by the Dublin Guard follow soon after Ballyseedy.

Fuller crawls away to the friendly home of the Currans nearby. They take him to the home of Charlie Daly the following day. His injuries are treated by a local doctor, Edmond Shanahan, who finds him in a dugout. He moves often in the coming months, including to the Burke and Boyle families, and stays in a dugout that had been prepared at the Herlihys for seven months.

A cover-up begins almost immediately. Paddy Daly’s communication to Dublin about returning the bodies to relatives differs significantly from Cumann na mBan statements, which Daly complains about as simple propaganda, and later that of Bill Bailey, a local who had joined the Dublin Guard, who tells Ernie O’Malley that the bodies were handed over in condemned coffins as a band played jolly music. Fuller is named amongst the dead in newspaper reports before it is realised that he had escaped. Daly then sends a communication to GHQ that Fuller is reported as having become “insane.” The Dublin Guard scours the countryside for Fuller. The official investigation into the killings is presided over by Daly himself, with Major General Eamon Price of GHQ and Colonel J. McGuinness of Kerry Command. It blames Irregulars for planting the explosives and exonerates the Irish Army soldiers, and this is read out in the Dáil by the Minister for Defence, Richard Mulcahy.

Contrary statements to the Irish Army’s submissions are effectively ignored. Lieutenant Niall Harrington of the Dublin Guard, describes the evidence to the court and the findings as “totally untrue,” explaining that the actions were devised and executed by officers of the Dublin Guard. He contacts Kevin O’Higgins, Minister for Justice and Vice-President, a family friend, to deplore the findings. O’Higgins speaks to Richard Mulcahy, who does nothing. In a separate incident, Free State Lieutenant W.McCarthy, who had been in charge of about twenty prisoners, says that five of them had been removed in the night. They were reportedly shot in the legs then blown up by, in his words, “…a Free State mine, laid by themselves.” He resigns in protest. A Garda Síochána report into the events is also dismissed and is not made public for over 80 years.

Fuller leaves the IRA after the Civil War and follows a career as a farmer in Kerry. He joins Fianna Fáil, the political party founded by Republican leader Éamon de Valera in 1926 after a split from Sinn Féin. He is elected to the 9th Dáil on his first attempt, representing Fianna Fáil at the 1937 Irish general election, as the last of three Fianna Fáil TDs to be elected to the four seat Kerry North constituency. He is re-elected to the 10th Dáil at the 1938 Irish general election, when Fianna Fáil again wins three out of four seats, but loses his seat at the 1943 Irish general election to the independent candidate Patrick Finucane. He returns to farming thereafter.

Fuller never once mentions the Ballyseedy incident from a political platform and states later that he bore no ill-will towards his captors or those who were involved in his attempted extrajudicial killing. He does not want the ill feeling passed on to the next generation. He speaks publicly about the events in 1980, a few years before his death, on Robert Kee‘s groundbreaking BBC series Ireland: A Television History.

Fuller dies in Edenburn Nursing Home, Tralee, on February 23, 1984. He is buried near the Republican plot in Kilflynn where colleagues O’Shea, Tuomey and Timothy ‘Aero’ Lyons are buried.

Fuller’s son Paudie establishes the Stephen Fuller Memorial Cup for dogs of all ages, contested annually on the family farm.

Fuller’s fame largely rests on one night at Ballyseedy. To trace him through the rural society from which he and his fellow Volunteers originated and in which his life was spent, however, gives a fuller understanding of the devastating effects of the conflicts of 1916–23 on a tightly knit rural and small-town society, dominated by extended families of farmers and their service-industry relatives, and of how that society remembered and forgot those traumas.

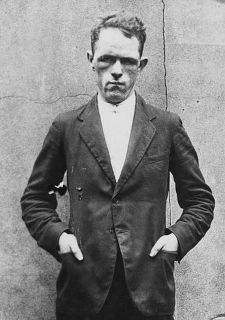

(Pictured: Stephen Fuller’s grave in Kilflynn, by St. Columba’s Heritage Centre)