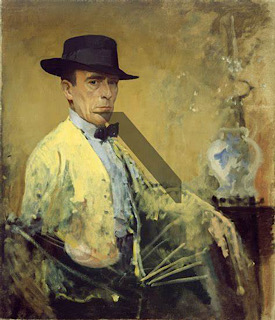

Colin Middleton MBE, Northern Irish landscape artist, figure painter, and surrealist, is born on January 29, 1910, in Victoria Gardens in north Belfast. Hus prolific output in an eclectic variety of modernist styles is characterised by an intense inner vision, augmented by his lifelong interest in documenting the lives of ordinary people. He has been described as “Ireland’s greatest surrealist.”

Middleton is the only child of damask designer Charles Middleton. He attends the nearby Belfast Royal Academy until 1927 and then continues his studies with night classes at Belfast School of Art where he trains in design under the Cornish artist Newton Penprase. However, he finds the college too traditional in outlook, as his first influence, his father, had been a follower of European Modernism, particularly the Impressionists.

Middleton shows his first works with the Ulster Academy of Arts in 1931, where he exhibits frequently until the late nineteen-forties. He first comes to public attention with the inclusion of his works in the groundbreaking inaugural exhibition of the Ulster Unit at Locksley Hall, Belfast, in December 1933. The Ulster Unit is a short-lived grouping of Ulster artists who take their inspiration from Paul Nash’s Unit One formed earlier in the same year. Just two years thereafter in the same year, he marries Maye McLain, also an artist and a domestic science teacher, who unfortunately dies four years later. He is also a poet and writer, whom along with his wife, is an active member of the Northern Drama League in the 1930s, with whom he designs sets. After the death of his first wife he destroys all of his early paintings and enters a period of seclusion at his mother’s home outside Belfast. He becomes a follower of Vincent van Gogh and James Ensor after viewing exhibitions in London and Belgium respectively. On his return to Ulster he begins to experiment with styles derived from European Modernism, the antithesis to traditional academism. Throughout the 1930s he is also a keen follower of Paul Nash, Tristam Hillier and Edward Wadsworth. After exposure to the works of Salvador Dalí, he declares himself “the only surrealist painter working in Ireland.”

Middleton’s work first appears at the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1938 where he shows intermittently until the final year of his life. He participates in an exhibition at 36 Arthur Street, Belfast, with the Czech artist Otakar Gregor, Joan Loewenthal and Sidney Smith in aid of the war effort at the end of 1940. He completes three paintings immediately after the Belfast Blitz and the trauma of the events prevent him from working for six months before his work is included in a portfolio of lithographs published by the Ulster Academy in December 1941 to raise money for rebuilding the Ulster Children’s and Women’s Hospital which had been destroyed in the Blitz earlier in the year.

Middleton’s first solo exhibition is given by the Belfast Municipal Museum and Art Gallery in 1943. It is the first exhibition staged at the gallery when it re-opens after the Belfast Blitz. At the time it is the largest one-person show the gallery has staged comprising one hundred fifteen works and it is also the first solo exhibition accorded to a local contemporary artist by the gallery. In an interview with Patrick Murphy in 1980, he says that the paintings represent “a first endeavour to harmonize the seemingly opposed and conflicting tendencies in human nature.” Dickon Hall says of this period that “Middleton’s painting is dominated by the female form; it is only rarely that men appear in his work. In part these women reflect his experience of Belfast and the difficult conditions that so many lived through.” This can be seen in the three female figures of The Poet’s Garden (1943), and even more so in The Conspirators (1942), both of which are featured in the 1943 exhibition. “The female form, pictorially and symbolically, becomes the landscape and the life force.”

The Belfast exhibition is followed by his first one-man show at the Grafton Galleries, Dublin, in 1944. In the following year he debuts at the Irish Exhibition of Living Art where he returns on a number of occasions, particularly in the periods 1949–55 and 1963–71. In 1945, he is married for the second time, to Kate Giddens, after both are named co-respondents at the Belfast High Court a few months earlier, in civil servant Lionel P. Barr’s application for a decree nisi. The suit is undefended and the couple has costs awarded against them. In the same year Middleton returns to the Belfast Museum for a solo exhibition arranged by the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts. He is a founding member of the Northern Ireland branch of the Artists’ International Association, who show at the Belfast Municipal Gallery in spring 1945. Other members include Joan Loewenthal, Kathleen Crozier, Pat Hicking, Trude Neu, Sidney Smith, Nevill Johnston, George Campbell and Gerard Dillon.

Middleton’s work is displayed in New York‘s Associated American Artists gallery in 1947 with a selection of works chosen by Dublin art critic Theodore Goodman that includes paintings by his Northern contemporaries Daniel O’Neill, George Campbell, Gerard Dillon and Patrick Scott. He also retires from the family business that year to devote his time to painting, having worked at the business since his father’s death in 1933. He then takes his wife and child to live and work on John Middleton Murry’s Suffolk commune for a short period, before returning to Belfast in 1948. Their life in Suffolk is not a success as the family suffers from ill health, but the experience of working the land is to prove a profound influence on his future work.

In 1949, Middleton shows his first works at the Oireachtas na Gaeilge, where he returns periodically until 1977. Upon their return from Suffolk, his wife sends Victor Waddington photos of his work whereupon Waddington comes to represent him for a period of five years, until the Waddington Galleries face financial hardship in 1958. It is Waddington’s patronage that enables the Middleton family to live and work in Ardglass, County Down, for four years from 1949, which Middleton later describes as the happiest time of his life. When his works are displayed at Victor Waddington’s Dublin gallery in that same year, it acts as a springboard that opens Middleton’s work to an international audience. Group exhibitions in Boston and London follow in 1950 and 1951 respectively.

Middleton’s first solo show at London’s Tooth Gallery takes place in 1952, where his work had been shown in the previous year.

In 1953, Middleton moves to Bangor, County Down, where he designs for Marjery Mason‘s The Repertory Theatre. He later designs sets for the Circle Theatre and the Lyric Theatre, including the sets for a series of W. B. Yeats’s plays in 1970, and Seán O’Casey‘s Red Roses for Me in 1972, both at the latter. In 1952, he exhibits alongside Daniel O’Neill, Nevill Johnson, Gerard Dillon and Thurloe Connolly at the Tooth Galleries in London. He begins his career as an art teacher by the invitation of James Warwick who offers him a one year part-time post at the Belfast College of Art in 1954. That year he shows forty-two works at the Belfast Municipal Gallery under the auspices of the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts. In the following year he delivers full-time classes at the Coleraine Technical School, before becoming head of art at Friends’ School, Lisburn in 1961 where he remains until 1970. He lives on Plantation Avenue in Lisburn for nine years next door to fellow artist and pedagogue Dennis Osborne, who presents a portrait of Middleton at the annual exhibition of the Royal Ulster Academy in 1965.

A poet and musician, Middleton also produces murals, mosaics and posters. One such mural is commissioned for a house in Ballymena designed by the architect Noel Campbell in an international modernist style in 1951, and other works include a mosaic for a school in Lisburn, and a mural in a health clinic. He shows in many group shows throughout the fifties including the Royal Academy of Arts in 1955, in addition to more solo exhibitions at the Waddington Galleries in 1955, and his first showing at the Richie Hendricks Gallery in 1958. Of the Waddington exhibition The Dublin Magazine writes: “Apart from the brilliance of his paint, he has one rare quality in his inexhaustible capacity for wonder.”

Middleton shows in the Arts Council of Northern Ireland‘s gallery in 1965 with additional works at the Bell Gallery and his Bruges Series is shown at Alice Berger Hammerschlag’s New Gallery upon his return from a Belgian trip in 1966. The Arts Council of Northern Ireland suffers an extensive fire at their storage facility in south Belfast in autumn 1967 which decimates their collection of contemporary art and theatre costumes. Losses include several of Middleton’s paintings, in addition to the works of many other leading Ulster artists such as William Conor and T. P. Flanagan. He Is among the prizewinners at the Arts Council of Northern Ireland’s 4th Open Painting Exhibition in 1968. In the same year, John Hewitt curatea a joint exhibition of his paintings with T. P. Flanagan at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry.

The Arts Council hosts a joint retrospective of Middleton’s work in co-operation with the Scottish Arts Council in 1970. A major retrospective is to follow at the Ulster Museum and the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art in Dublin in 1976. Comprising almost three hundred exhibits, the show is accompanied by a monograph written by Middleton’s lifelong friend, the patron and poet John Hewitt. Hewitt later bequeaths his art collection, including several of Middleton’s paintings to the Ulster Museum.

The Royal Mail uses Middleton’s painting of Slieve na Brock in the Mourne Mountains to commemorate the Ulster ’71 exhibition in a series of postage stamps that also feature the work of Thomas Carr and T. P. Flanagan. In 1972, Middleton tours extensively with his wife visiting Australia for two months and shows his works from the trip at the McClelland International Galleries on Belfast’s Lisburn Road the following year. In 1973 he also visits Barcelona and later shows a series of surrealist works inspired by the two trips at the Tom Caldwell Gallery in Belfast.

Middleton lives the last twelve years of his life in Bangor, County Down.

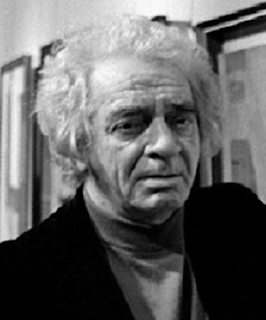

Middleton dies of leukemia in Belfast City Hospital on December 23, 1983. He is survived by his wife Kate, their daughter and a step-daughter. His son predeceases him by a year. Christie’s of London is entrusted with the sale of his studio works in 1985. The works are displayed before auction in both Dublin and Belfast during August 1985. In 2005, the Ulster History Circle unveils a commemorative blue plaque at his former home on Victoria Road in Bangor.

In the 1970s, the Arts Council of Northern Ireland commissions a documentary film portrait of Middleton entitled Trace of a Thorn, which is written and narrated by the Belfast poet Michael Longley. Hus works can be seen in many private and public collections including the Ulster Museum, Irish Museum of Modern Art, the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery, National Gallery of Ireland, National Gallery of Victoria, Herbert Art Gallery and University of Oxford.

In September 2023, eighty years since the ground-breaking exhibition Middleton held at the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery, now the Ulster Museum, and forty years after his death, the Ulster Museum holds a new exhibition of his works, celebrating his association with Belfast, the city of which he says, “I belong here as I never belonged anywhere else in the country.” This exhibition brings together works held in the public collection with those from private lenders to provide a full picture of the artist’s talent and life.

Middleton wins the Royal Dublin Society‘s Taylor Scholarship worth £50 in 1932, and two further awards of £10 in 1933. In 1935, he is elected associate of the Ulster Academy, inducted alongside Helen Brett, Kathleen Bridle, Patrick Marrinan, Maurice Wilks, Romeo Toogood and William St. John Glenn, and in 1948 he becomes an elected Academician at the same.

In 1968, Middleton is appointed MBE in the Queen’s birthday honours list, and in 1969 he is elected an associate at the Royal Hibernian Academy with full membership conferred just a year later. He is awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree from Queen’s University Belfast in 1972. The Arts Council of Northern Ireland grants him a substantial subsistence award in 1970 which covers two years enabling him to retire from teaching to concentrate on painting full-time. In the same year, the Arts Council of Northern Ireland also commissions him to paint a portrait of their director, Kenneth Jamison.