Intense riots between Protestants and Roman Catholics erupt in Derry and Belfast on June 27, 1970. During the evening, loyalist paramilitaries make incursions into republican areas of Belfast. This leads to a prolonged gun battle between republicans and loyalists. The rioting in both Belfast and Derry takes place despite the presence of more than 8,000 British soldiers, backed up by armored vehicles and helicopters.

The rioting follows the June 26 jailing of Bernadette Devlin, the 23‐year‐old Roman Catholic leader, who had recently been reelected to Parliament in London. She had been convicted of riotous behavior during violence in Derry in August 1969 and sentenced to six months in prison.

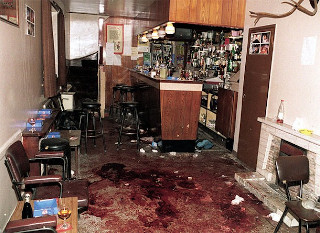

The rioting in Belfast begins after Catholic youths hurl stones and disrupt a parade by the militantly Protestant Orange Order. About 100 persons are injured badly enough to be treated in hospitals. A bakery and a butcher shop in a shopping center are set afire and a police station is wrecked with iron bars and clubs. The scene of the rioting is at the intersection of Mayo Street and Springfield Road in a mixed Protestant‐Catholic area.

Armed British soldiers, in visors and helmets and carrying riot shields, separate ugly, shouting mobs of Catholics and Protestants. The troops use tear gas in an effort to break up the crowd and at one point send 1,000 people, including women and children, fleeing with tears streaming down their faces.

There is civilian sniping and firing by British troops in two riot areas — the Springfield Road area and the Crumlin Road area – where rival crowds from segregated slum streets clash later in the afternoon.

At night British soldiers seal off the riot areas to all but military vehicles. Armored cars with machine guns ready stand in the streets, which are littered with glass and stones. Hundreds of soldiers in full battle dress stand against the seedy red‐brick shops and houses.

However, the crowds continue to gather. Buses are set afire, and late at night the army uses tear gas again to drive the mobs away. As rioting erupts in other parts of Belfast, 4,000 British soldiers are said to have been sent into the riot areas. The police are harassed by a half dozen fires around the city. Some of the fires are started with battery devices according to the police.

In Derry, Catholic youths attack soldiers and policemen with stones, bottles and gasoline bombs. The youths begin re‐erecting the barricades that had shielded the Catholic Bogside slum area during rioting the previous year. Ninety-two soldiers are injured and a paint shop near Bogside is set ablaze after looting by children who appear to be no more that 11 or 12 years old.

The wave of agitation begins in October 1968, when a largely Catholic civil rights movement takes to the streets to demand an end to anti‐Catholic discrimination in voting rights, jobs and housing. The Unionist Government in Belfast, which considers itself aligned with the Conservative Party in London, responds reluctantly to the street violence. However, under intense prodding by the Labor Government, it enacts many of the demanded reforms.

However, a Protestant backlash ensues, encouraged by the fiery evangelical preacher, the Rev. Ian Paisley. Paisley fans the latent fear that Northern Ireland‘s Catholics seek to unite Ireland into a Catholic state under Dublin. In the view of many observers, the Protestants have never shared power nor prestige with the Catholic minority, while the Catholics have taken an ambiguous view on whether they wanted to be British or Irish.

(From: “New Rioting Flares in Northern Ireland; 4 Dead and 100 Hurt” by John M. Lee, The New York Times, June 28, 1970)

A

A