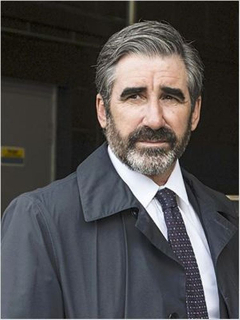

John Magee SPS, a Roman Catholic bishop emeritus in Ireland, is born in Newry, County Down, Northern Ireland, in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Dromore, on September 24, 1936. He is Bishop of Cloyne from 1987 to 2010. Following scandal he resigns from that position on March 24, 2010, becoming a bishop emeritus. He is the only person to have been private secretary to three popes.

Magee’s father is a dairy farmer. He is educated at St. Colman’s College in Newry and enters the St Patrick’s Missionary Society at Kiltegan, County Wicklow, in 1954. He also attends University College Cork (UCC) where he obtains a degree in philosophy before going to study theology in Rome, where he is ordained priest on March 17, 1962.

Magee serves as a missionary priest in Nigeria for almost six years before being appointed Procurator General of St. Patrick’s Society in Rome. In 1969, he is an official of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples in Rome, when he is chosen by Pope Paul VI to be one of his private secretaries. On Pope Paul’s death he remains in service as a private secretary to his successor, Pope John Paul I and Pope John Paul II. He is the only man to hold the position of private secretary to three Popes in Vatican history. He also acts as chaplain to the Vatican’s Swiss Guard.

Magee is appointed papal Master of Pontifical Liturgical Celebrations in 1982, and is appointed Bishop of the Diocese of Cloyne on February 17, 1987. He is consecrated bishop on March 17, 1987, Saint Patrick’s Day, by Pope John Paul II at St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.

On April 28, 1981, Magee travels, without the knowledge or approval of the Vatican’s Secretariat of State, to the Long Kesh Detention Centre outside Belfast to meet with Irish Republican Army (IRA) hunger striker Bobby Sands. He seeks, unsuccessfully, to convince Sands to end his hunger strike. Sands dies the following week.

Magee plays a role in the Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference where he is featured in the modernisation of the liturgy in Ireland. His pastoral approach places heavy emphasis on the promotion of vocations to the priesthood but, after some initial success, the number of vocations in the diocese of Cloyne declines, a trend reflected across the island of Ireland. He appoints Ireland’s first female “faith developer” and entrusts her with the task of transforming an Irish rural diocese into a cosmopolitan pastoral model using techniques borrowed from several urban dioceses in the United States.

Magee involves himself in a dispute with the Friends of St. Colman’s Cathedral, a local conservationist group in Cobh which organises an effective and professional opposition to the Bishop’s plans to re-order the interior of the cathedral, plans similar to previous re-orderings in Killarney, Cork and Limerick cathedrals. In an oral hearing conducted by An Bord Pleanála, the Irish Planning Board, it emerges that irregularities have occurred in the planning application that are traced to Cobh Town Council, which accommodates the Bishop’s plans to modify the Victorian interior designed by E. W. Pugin and George Ashlin. On June 2, 2006, when Bishop Magee was in Lourdes, An Bord Pleanála directs Cobh Town Council to refuse the Bishop’s application.

On July 25, 2006, Magee publishes a pastoral letter stating: “As a result of An Bord Pleanála’s decision, the situation concerning the temporary plywood altar still remains unresolved and needs to be addressed. The Diocese will initiate discussions with the planning authorities in an attempt to find a solution, which would be acceptable from both the liturgical and heritage points of view.”

A diocesan official explains that the bishop does not wish to institute a judicial review in the Irish High Court because of the financial implications of such an action and because of the bishop’s desire to avoid a Church-State clash.

Claims that the decision of An Bord Pleanála infringes the constitutional property rights of religious bodies are dismissed when it is revealed that the cathedral is the property of a secular trust established in Irish law. It is estimated that Bishop Magee spent over €200,000 in his bid to re-order the cathedral. The controversy is reported even outside Ireland.

A February 2006 article by Kieron Wood in The Sunday Business Post claims that Magee does not have the backing of the Vatican in his proposals for St. Colman’s. At the oral hearing of An Bord Pleanála he is requested to provide a copy of the letter from the Vatican in which he claims he has been given approval for the modernising of the cathedral. The letter that he produces is a congratulatory message dated December 9, 2003 to the team of architects who worked on the cathedral project from Cardinal Francis Arinze, Prefect of the Dicastery for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. The whole text of this letter is then reproduced in a publication called Conserving Cobh Cathedral: The Case Stated pp. 108–109.

At a meeting of his liturgical advisers and diocesan clergy in November 2006, Bishop Magee speaks of his conversation with the Pope in the course of that ad limina visit at the end of the previous month. He mentions that he has been closely questioned on several aspects of his proposals to re-order St. Colman’s Cathedral. It is obvious, he says, that the Pope has been kept well informed of the entire issue.

Bishop Magee’s contribution to the ad limina visit concerns not only his diocese of Cloyne but also ceremonial matters on behalf of the Conference. He also facilitates the broadcasting, in coincidence with the visit, of a life of Pope John Paul I prepared some months earlier by Italian state television (RAI). In an interview published on the Italian Catholic daily Avvenire on October 26, 2006, Cardinal Secretary of State Tarcisio Bertone criticises the image that the programme presents of Pope John Paul I.

After the ad limina visit, Bishop Magee represents the Irish bishops at a meeting in Rome of the International Commission for Eucharistic Congresses.

In 2007, for the third year in succession, Magee fails to complete his personal schedule of confirmations in Cloyne diocese. On May 12, 2007, he is admitted to the Bon Secours Hospital in Cork to undergo a knee replacement operation. All official engagements are cancelled for the next ten weeks to allow him to recuperate, after which he resumes work.

In December 2008, Magee is at the centre of a controversy concerning his handling of child sexual abuse cases by clergy in the diocese of Cloyne. Calls for his resignation follow. On March 7, 2009, he announces that, at his request, the Pope has placed the running of the diocese in the hands of Dermot Clifford, metropolitan archbishop of the Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly, to whose ecclesiastical province the diocese of Cloyne belongs. Magee remains Bishop of Cloyne, but withdraws from administration in order, he says, to dedicate his full-time to the matter of the inquiry. On March 24, 2010, the Holy See announces that Magee has formally resigned from his duties as Bishop of Cloyne. He is eventually succeeded by Canon William Crean whose appointment comes on November 25, 2012.

The subsequent report of the Irish government judicial inquiry, The Cloyne Report, published on July 13, 2011, finds that Bishop Magee’s second in command, Monsignor Denis O’Callaghan, then the parish priest of Mallow, had falsely told the Government and the HSE in a previous inquiry that the diocese was reporting all allegations of clerical child sexual abuse to the civil authorities.

The inquiry into Cloyne – the fourth examination of clerical abuse in the Church in Ireland – finds the greatest flaw in the diocese is repeated failure to report all complaints. It finds nine allegations out of 15 were not passed on to the Garda.

Speaking in August 2011, Magee says that he felt “horrified and ashamed” by abuse in his diocese. He says he accepts “full responsibility” for the findings. “I feel ashamed that this happened under my watch – it shouldn’t have and I truly apologise,” he says. “I did endeavour and I hoped that those guidelines that I issued in a booklet form to every person in the diocese were being implemented but I discovered they were not and that is my responsibility.”

Magee also offers to meet abuse victims and apologise “on bended knee.” He says he had been “truly horrified” when he read the full extent of the abuse in the report. However, a victim says apologies would “never go far enough.” “It’s too late for us now, the only thing it’s not too late for is that maybe there will be a future where people will be more enlightened, more aware and protect their children better,” she says. Asked about restitution for victims, Magee says it is a matter for the Cloyne Diocese.