The Gibbet Rath executions, sometimes called the Gibbet Rath massacre, refers to the execution of several hundred surrendering rebels by government forces during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 at the Curragh of Kildare on May 29, 1798.

News of the outbreak of the rebellion prompts Major-General Sir James Duff, Military Commander in Limerick, to gather a force of about 600 men, mainly Dublin militia members, backed up by seven artillery pieces, and sets out on a forced march to Dublin on May 27. His twin objectives are to restore communications between the two cities and to crush any resistance encountered on the way. As the soldiers enter County Kildare, they discover the bodies of several rebel victims, among them Lieutenant William Giffard, the son of the commander of the Dublin militia, Captain John Giffard, which reportedly inflames the soldiers.

However, by the time Duff’s column arrives in Monasterevin in County Kildare, at 7:00 a.m. on May 29, the bulk of the rebel forces have already accepted a government amnesty from Generals Gerard Lake and Ralph Dundas, following their defeat at the Battle of Kilcullen and had surrendered at Knockaulin Hill, several kilometres to the east of the Curragh on May 27. Not aware that the rebels are gathering to surrender on the Curragh plain, Duff reinforces his column and marches to the nearby town of Kildare, and on to the adjacent southwest corner of the Curragh.

Duff’s force had by now grown to 700 militia, dragoons and yeomanry with four pieces of artillery, three having been presumably left at Monasterevin. The designated place of surrender, the ancient fort of Gibbet Rath, is a wide expanse of plain with little or no cover for several kilometres around but neither the rebels nor Duff’s force have seemingly any reason to fear treachery as a separate peaceful surrender to General Dundas at Knockaulin Hill, who is accompanied only by two dragoons, has been successfully accomplished without bloodshed.

By the time of Duff’s arrival at Gibbet Rath on the morning of May 29, an army of between 1,000 and 2,000 rebels is waiting to surrender in return for the promised amnesty. They are subjected to an angry tirade for their treason by Duff who orders them to kneel for pardon and then to stack their arms. Shortly after the weapons are stacked, an infantry and cavalry assault results in the death of about 350 men. Accounts of why the massacre began differ. Rebel claims that Duff orders his troops to attack the disarmed and surrounded men are denied by Duff himself who claims that the rebels fired on his men, while another source records “one man in the crowd, saying he would not hand over his fire-lock loaded, blazed it off in the air”.

However, Duff redrafts his own official report of the engagement before submission to Dublin Castle, his final draft is transmitted without references to his knowledge of the surrender preparations. The original report reads as follows with the items in brackets excised from his final report:

“My Dear Genl. (I have witnessed a melancholy scene) We found the Rebels retiring from this Town on our arrival armed. We followed them with Dragoons; I sent on some of the Yeomen to tell them, on laying down their arms, they should not be hurt. Unfortunately some of them Fired on the Troops; from that moment they were attacked on all sides, nothing could stop the Rage of the Troops. I believe from Two to Three hundred of the Rebels were killed. (They intended, we are told, to lay down their arms to General Dundas). We have 3 men killed & several wounded. I am too fatigued to enlarge. I have forwarded the mails to Dublin.”

The grieving Captain John Giffard expresses his own satisfaction as follows:

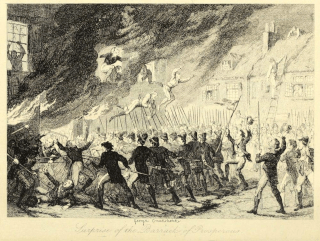

“My troops did not leave my hero unavenged – 500 rebels bleaching on the Curragh of Kildare—that Curragh over which my sweet innocent girls walked with me last Summer, that Curragh was strewed with the vile carcasses of popish rebels and the accursed town of Kildare has been reduced to a heap of ashes by our hands.”

General Duff receives no censure for the massacre and, upon his arrival in Dublin the following day, is feted as a hero by the population who honour him with a victory parade. General Dundas, by contrast, is denounced for having shown clemency toward the rebels. However, because of the massacre, wavering rebels are discouraged from surrendering and there are no further capitulations in County Kildare until the final surrender of William Aylmer in July. Dr. Chambers considers that Lake and Duff are not in communication about the surrenders, being on opposite sides of the Curragh. Duff and his 500 men arrive in Kildare after a forced march from Limerick and find it sacked by the rebels, along with the piked body of Duff’s nephew.

Duff is later involved in an unsuccessful campaign after the Battle of Vinegar Hill to trap and destroy a surviving rebel column in Wexford led by Anthony Perry who fights and eludes Duff’s forces at the battle of Ballygullen/Whiteheaps on 5 July.

(Pictured: The statue of Saint Brigid at the Market Square of Kildare which is dedicated to the memory of the victims at Gibbet Rath)