The Clan na Gael, an Irish republican organization in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, is founded by John Devoy, Daniel Cohalan, and Joseph McGarrity in New York City on June 20, 1867. It is the successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister organization to the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). It has shrunk to a small fraction of its former size in the 21st century.

As Irish immigration to the United States begins to increase in the 18th century many Irish organizations are formed. In the later part of the 1780s, a strong Irish patriot character begins to grow in these organizations and amongst recently arrived Irish immigrants.

In 1858, the IRB is founded in Dublin by James Stephens. In response to the establishment of the IRB in Dublin, a sister organization is founded in New York City, the Fenian Brotherhood, led by John O’Mahony. This arm of Fenian activity in America produces a surge in radicalism among groups of Irish immigrants, many of whom had recently emigrated from Ireland during and after the Great Famine.

In October 1865, the Fenian Philadelphia Congress meets and appoints the Irish Republican Government in the United States. Meanwhile in Ireland, the IRB newspaper The Irish People is raided by the police and the IRB leadership is imprisoned. Another abortive uprising occurs in 1867, but the British remain in control.

After the 1865 crackdown in Ireland, the American organization begins to fracture over what to do next. Made up of veterans of the American Civil War, a Fenian army is formed. While O’Mahony and his supporters want to remain focused on supporting rebellions in Ireland, a competing faction, called the Roberts, or senate wing, wants this Fenian Army to attack British bases in Canada. The resulting Fenian raids strain U.S.–British relations. The level of American support for the Fenian cause begins to diminish as the Fenians are seen as a threat to stability in the region.

After 1867, the Irish Republican Brotherhood headquarters in Manchester chooses to support neither of the existing feuding factions, but instead promotes a renewed Irish republican organization in America, to be named Clan na Gael.

According to John Devoy in 1924, Jerome James Collins founds what is then called the Napper Tandy Club in New York on June 20, 1867, Wolfe Tone‘s birthday. This club expands into others and at one point at a picnic in 1870 is named the Clan na Gael by Sam Cavanagh. This is the same Cavanagh who killed the informer George Clark, who had exposed a Fenian pike-making operation in Dublin to the police.

Collins, who dies in 1881 on the disastrous Jeannette Expedition to the North Pole, is a science editor on the New York Herald, who had left England in 1866 when a plot he was involved in to free the Fenian prisoners at Pentonville Prison was uncovered by the police. Collins believes at the time of the founding in 1867 that the two feuding Fenians branches should patch things up.

The objective of Clan na Gael is to secure an independent Ireland and to assist the Irish Republican Brotherhood in achieving this aim. It becomes the largest single financier of both the Easter Rising and the Irish War of Independence.

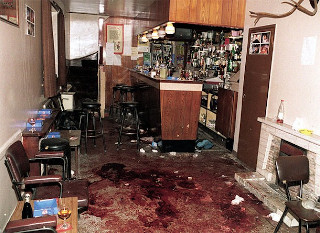

Clan na Gael continues to provide support and aid to the Irish Republican Army (IRA) after it is outlawed in Ireland by Éamon de Valera in 1936 but becomes less active in the 1940s and 1950s. However, the organization grows in the 1970s. The organization plays a key part in the Irish Northern Aid Committee (NORAID) and is a prominent source of finance and weapons for the Provisional Irish Republican Army during the Troubles in Northern Ireland in 1969–1998.

The Clan na Gael still exists today, much changed from the days of the Catalpa rescue. In 1987 the policy of abstentionism is abandoned. As recently as 1997 another internal split occurs as a result of the IRA shift away from the use of physical force as a result of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. The two factions are known to insiders as Provisional Clan na Gael (allied to Provisional Sinn Féin/IRA) and Republican Clan na Gael (associated with both Republican Sinn Féin/Continuity IRA and 32 County Sovereignty Movement/Real IRA, though primarily the former). These have been listed as terrorist organizations at various times by the UK Government.

(Pictured: Clan na Gael marching in the 1970 St. Patrick’s Day Parade in Philadelphia, photograph by John Hamilton)

The

The