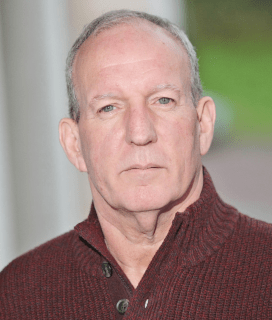

A rally of twelve to fifteen thousand Peace People from both north and south takes place at the new bridge over the River Boyne at Drogheda, County Louth, on December 5, 1976. In general, the Peace People’s goals are the dissolution of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and an end to violence in Northern Ireland. The implicit goals of the Peace People rallies are delegitimization of violence, increasing solidarity, and gaining momentum for peace.

In the 1960s, Northern Ireland begins a period of ethno-political conflict called the Troubles. Through a series of social and political injustices, Northern Ireland has become a religiously divided society between historically mainland Protestants and Irish Catholics. Furthermore, the Irish people have become a fragmented body over a range of issues, identities, circumstances and loyalties. The conflict between Protestants and Catholics spills over into violence, marked by riots and targeted killings between the groups beginning in 1968. In addition, paramilitary groups, including the prominent IRA, launch attacks to advance their political agendas.

The violence continues to escalate. On August 10, 1976, Anne Maguire and her children are walking along Finaghy Road North in Belfast. Suddenly, a Ford Cortina slams into them. The car is being driven by Danny Lennon, who moments before had been shot dead by pursuing soldiers. The mother is the only survivor. The collision kills three of her four children, Joanne (8), John (2), and Andrew (6 months). Joanne and Andrew die instantly while John is injured critically.

The next day, immediately following John’s death, fifty women from the Republican neighborhoods of Andersonstown and Stewartstown protest Republican violence by marching with baby carriages. That evening, Mairead Corrigan, Anne Maguire’s sister, appears on television pleading for an end to the violence. She becomes the first leader of the Peace People to speak publicly.

However, she was not the only one to initiate action. As soon as she hears Mairead speak on the television, Betty Williams begins petitioning door-to-door for an end to sectarian violence. She garners 6,000 signatures of support within a few days. This support leads directly into the first unofficial action of the Peace People. On 14 August, only four days after the incident, 10,000 women, both Protestant and Catholic, march with banners along Finaghy Road North, the place of the children’s death, to Milltown Cemetery, their burial site. This march mostly includes women along with a few public figures and men. The marchers proceed in almost utter silence, only broken by short bouts of singing from the nuns in the crowd and verbal and physical attacks by Republican opposition.

The following day, the three who become leaders of the Peace People – Mairead Corrigan, Betty Williams, and journalist Ciaran McKeown – come together for their first official meeting. During these initial meetings they establish the ideological basis of nonviolence and goals for the campaign. The essential goals for the movement are the dissolution of the IRA and an end to the violence in Northern Ireland. The goals of the campaign implicit in their declaration are awareness, solidarity, and momentum. Peace People’s declaration:

“We have a simple message to the world from this movement for Peace. We want to live and love and build a just and peaceful society. We want for our children, as we want for ourselves, our lives at home, at work, and at play to be lives of joy and peace. We recognise that to build such a society demands dedication, hard work, and courage. We recognise that there are many problems in our society which are a source of conflict and violence. We recognise that every bullet fired, and every exploding bomb make that work more difficult. We reject the use of the bomb and the bullet and all the techniques of violence. We dedicate ourselves to working with our neighbours, near and far, day in and day out, to build that peaceful society in which the tragedies we have known are a bad memory and a continuing warning.”

During the four-month campaign, Peace People and partners organize and participate in 26 marches in Northern Ireland, Britain, and the Republic of Ireland. In order to organize these marches effectively they establish their main headquarters in Belfast.

After the initial Finaghy Road March, the Peace People, both Protestants and Catholics, rally in Ormeau Park on August 21. The official Declaration of the Peace People is first read at this rally, the largest rally of the entire campaign. The group numbers over 50,000. The rally even includes some activists from the Republic of Ireland, most notably Judy Hayes from the Glencree Centre of Reconciliation near Dublin. After the rally, she and her colleagues return to the south to organize solidarity demonstrations.

In the few days before the next march, the organization “Women Together” request Peace People to call off the march, disapproving of Catholics and Protestants participating in a joint march. The Peace People are not dissuaded. The next Saturday, 27,000 people march along Shankill Road, the loyalist/Protestant neighborhood.

In the next three months, Peace People organize and participate in a rally every Saturday; some weeks even have two. Some of the most notable marches include the Derry/Londonderry double-march, the Falls march, the London march, and the Boyne march.

The Saturday following the Shankill march marks the Derry/Londonderry double-march. At this march, Catholics march on one side of the River Foyle and Protestants on the other. The groups meet on the Craigavon Bridge. Simultaneously, 50,000 people march in solidarity in Dublin.

On October 23, marchers meet in the Falls, Belfast, in the pouring rain on the same Northumberland street corner where the Shankill March had started. The Falls Road rally is memorable for the fear and violence that ensues. During this rally Sinn Féin supporters throw stones and bottles at the marchers. The attackers escalate the violence as the marchers near Falls Park. The marchers are informed by others that more attackers await them at the entrance to the park, inciting fear within the body of the rally. The leaders decide that this is an important moment of conflict in the rally and that they must push on. They continue verbally encouraging the marchers through the cloud of bottles, bricks, and stones.

The leaders plan to escalate the campaign momentum for the last two major symbolic rallies in London and Boyne, Drogheda. A week before the rallies, on November 20-21, they plan a membership drive. Over 105,000 people sign within two days.

The symbolic week of the culminating rallies begins on November 27 at the glamorous London Rally. They begin to march at Hyde Park, cut through Westminster Abbey, and end at Trafalgar Square. Some groups sing “Troops Out,” and others resound with civil rights songs.

On December 5, Peace People holds its final march of the campaign, along the River Boyne. The Northern and Southern Ireland contingents met at the Peace Bridge. This is an important point in the legacy of the Peace People movement. Now that the enthusiastic rallies are over, the people are responsible for the tedious local work and continuing the momentum and solidarity that the rallies have inspired. The shape of the Peace People is changing.

After the planned marches are over, the rally portion of the campaign fades and the Peace People take a new shape. Corrigan, Williams, and McKeown stop planning marches, but continue to be involved in action that takes the form of conferences and traveling overseas. However, the leaders begin doing more separated work. Ciaran McKeown increases his focus on radical political restructuring.

In 1977, Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan receive the Nobel Peace Prize. Issues regarding the use of the monetary award impact the two leaders’ relationships in an irreconcilable manner.

Due to the fact that many people, unlike McKeown, are less interested in the political side of the equation, the People continue actions along the lines of rallies and social work. Actions continue through the People’s initiative in the form of Peace Committees that each does separate work in local areas.

The Peace People makes a substantial impact. They help to de-legitimize violence, increase solidarity across sectarian lines, and develop momentum for peace. Although the violence does not fully subside until 1998 with the negotiation of political change, Ireland sees in 1976 one of its most dramatic decreases in political violence, accompanying the Peace People’s marches and rallies. The campaign dramatizes how tired the people are of bloodshed, their desperate desire for peace, and the clear possibility of alternatives.

(From: “Peace People march against violence in Northern Ireland, 1976” by Hannah Lehmann, Global Nonviolent Action Database, https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/, 2011 | Pictured: The Peace People organisation rally in Drogheda, County Louth, December 5, 1976)