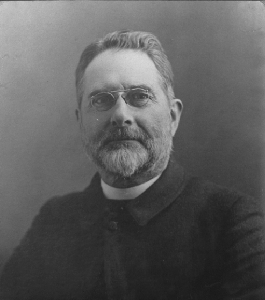

Charles Wood, composer and teacher, is born in Vicars’ Hill in the Cathedral precincts of Armagh, County Armagh on June 15, 1866. His pupils include Ralph Vaughan Williams at Cambridge and Herbert Howells at the Royal College of Music. For most of his adult life he lives in England, but preserves a lively interest in Ireland.

Wood is the fifth child and third son of Charles Wood, Sr. and Jemima Wood. He is a treble chorister in the choir of the nearby St. Patrick’s Cathedral. His father sings tenor as a stipendiary “Gentleman” or “Lay Vicar Choral” in the Cathedral choir and is also the Diocesan Registrar of the church. He is a cousin of Irish composer Ina Boyle.

Wood receives his early education at the Cathedral Choir School and also studies organ with two Organists and Masters of the Boys of Armagh Cathedral, Robert Turle and his successor Dr. Thomas Marks. In 1883 he becomes one of fifty inaugural class members of the Royal College of Music, studying composition with Charles Villiers Stanford and Charles Hubert Hastings Parry primarily, and horn and piano secondarily. Following four years of training, he continues his studies at Selwyn College, Cambridge through 1889, where he begins teaching harmony and counterpoint.

In 1889 he attains a teaching position at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, first as organ scholar and then as fellow in 1894, becoming the first Director of Music and Organist. He is instrumental in the reflowering of music at the college, though more as a teacher and organiser of musical events than as composer. After Stanford dies in 1924, Wood assumes his mentor’s vacant role as Professor of Music in the University of Cambridge.

Like his better-known colleague Stanford, Wood is chiefly remembered for his Anglican church music. As well as his Communion Service in the Phrygian mode, his settings of the Magnificat and Nunc dimittis are still popular with cathedral and parish church choirs, particularly the services in F, D, and G, and the two settings in E flat. During Passiontide his St. Mark Passion is sometimes performed, and demonstrates Wood’s interest in modal composition, in contrast to the late romantic harmonic style he more usually employs.

Wood’s anthems with organ, Expectans expectavi, and O Thou, the Central Orb are both frequently performed and recorded, as are his unaccompanied anthems Tis the day of Resurrection, Glory and Honour and, most popular of all, Hail, gladdening light and its lesser-known equivalent for men’s voices, Great Lord of Lords. All of Wood’s a cappella music demonstrates fastidious craftsmanship and a supreme mastery of the genre, and he is no less resourceful in his accompanied choral works which sometimes include unison sections and have stirring organ accompaniments, conveying a satisfying warmth and richness of emotional expression appropriate to his carefully chosen texts.

Wood collaborates with priest and poet George Ratcliffe Woodward in the revival and popularisation of renaissance tunes to new English religious texts, notably co-editing three books of carols. He also writes eight string quartets, and is co-founder of the Irish Folk Song Society in 1904.

He marries Charlotte Georgina Wills-Sandford, daughter of W. R. Wills-Sandford, of Castlerea, County Roscommon on March 17, 1898. Their son is killed in World War I.

Charles Wood dies on July 12, 1926 and is buried at the Ascension Parish Burial Ground in Cambridge alongside his wife.