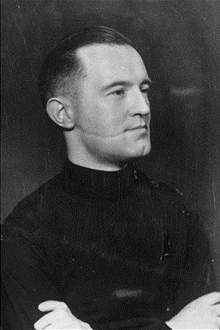

Robert Maire Smyllie, known as Bertie Smyllie, editor of The Irish Times for twenty years, dies on September 11, 1954.

Smyllie is born on March 20, 1893, at Hill Street, Shettleston, Glasgow, Scotland. He is the eldest of four sons and one daughter of Robert Smyllie, a Presbyterian printer originally from Scotland who is working in Sligo, County Sligo, at the time, and Elisabeth Follis, originally from Cork, County Cork. His father marries in Sligo on July 20, 1892, and later becomes proprietor and editor of the unionist Sligo Times. Smyllie attends Sligo Grammar School in 1906 and enrolls at Trinity College Dublin (TCD) in 1911.

After two years at TCD, Smyllie’s desire for adventure leads him to leave university in 1913. Working as a vacation tutor to an American boy in Germany at the start of World War I, he is detained in Ruhleben internment camp, near Berlin, during the war. As an internee, he is involved in drama productions with other internees. Following his release at the end of the war, he witnesses the German revolution of 1918–1919. During this period, he encounters revolutionary sailors from Kiel who temporarily make him a representative of the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council, and he observes key events including the looting of the Kaiser’s Palace and violent clashes between rival factions in Berlin. It is also during this period that he secures a personal interview with David Lloyd George at the Paris Convention of 1919. This helps Smyllie gain a permanent position with The Irish Times in 1920, where he quickly earns the confidence of editor John Healy. Together, they take part in secret but unsuccessful attempts to resolve the Irish War of Independence.

Smyllie contributes to the Irishman’s Diary column of the paper from 1927. In 1927, he publishes an exclusive report outlining a draft government including both Labour Party and Fianna Fáil TDs, signaling the volatile politics of the early state years.

Smyllie’s knowledge of languages (particularly the German he had learned during his internment) led to numerous foreign assignments. His reports on the rise of National Socialism in 1930s Germany are notably prescient and instill in him a lasting antipathy towards the movement.

When Healy dies in 1934, Smyllie becomes editor of The Irish Times and also takes on the role of Irish correspondent for The Times (London), a position that brings significant additional income. Under Healy’s leadership, The Irish Times shifted from representing the Anglo-Irish ascendancy to becoming an organ of liberal, southern unionism, and eventually becomes a critical legitimising force in the Irish Free State. Smyllie enthusiastically supports this change. He establishes a non-partisan profile and a modern Irish character for the erstwhile ascendancy paper. For example, he drops “Kingstown Harbour” for “Dún Laoghaire.” He also introduces the paper’s first-ever Irish-language columnist. He is assisted by Alec Newman and Lionel Fleming, recruits Patrick Campbell and enlists Flann O’Brien to write his thrice-weekly column “Cruiskeen Lawn” as Myles na gCopaleen. As editor, he introduces a more Bohemian and informal style, establishing a semi-permanent salon in Fleet Street’s Palace Bar. This becomes a hub for journalists and literary figures and a source of material for his weekly column, Nichevo.

One of Smyllie’s early political challenges as editor concerns the Spanish Civil War. At a time when Irish Catholic opinion is strongly pro-Franco, he ensures The Irish Times coverage is balanced and fair, though advertiser pressure eventually forces the withdrawal of the paper’s young reporter, Lionel Fleming, from the conflict. His awareness of the looming European crisis earns him the Order of the White Lion of Czechoslovakia in 1939. However, during World War II, he clashes with Ireland’s censorship authorities, especially under Minister Frank Aiken. He challenges their views both publicly and privately, though his relationship with the editor of the Irish Independent, Frank Geary, is cold, reducing the effectiveness of their joint opposition to censorship.

During the 1943 Irish general election, Smyllie uses the paper to promote the idea of a national government that could represent Ireland with authority in the postwar world. He praises Fine Gael’s proposal for such a government and criticises Éamon de Valera for dismissing it as unrealistic. This leads to a public exchange between de Valera and Smyllie, with the latter defending The Irish Times’s role as a constructive voice for Ireland’s future rather than a partisan interest.

Following the war, Smyllie’s editorial stance shifts toward defending Ireland’s neutrality and diplomatic position. When Winston Churchill accuses de Valera of fraternising with Axis powers, Smyllie counters by revealing Ireland’s covert collaboration with the Allies, such as military and intelligence cooperation, despite official neutrality. In the same period, he continues to oppose censorship, particularly the frequent banning of Irish writers by the Censorship of Publications Board. This opposition features prominently in a controversy on The Irish Times letters page in 1950, later published as the liberal ethic. The paper also adopts a critical stance toward the Catholic Church, notably during the 1951 resignation of Minister for Health Noël Browne amid opposition from bishops and doctors to a national Mother and Child Scheme. His editorials suggest the Catholic Church is effectively the government of Ireland, though he maintains a cordial relationship with Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, who invites him annually for dinner.

Smyllie is also wary of American foreign policy, showing hostility particularly during the Korean War. American diplomats in Dublin allege that Smyllie is “pro-communist“. Despite growing readership among an educated Catholic middle class, The Irish Times’s circulation in 1950 remains under 50,000, far below the Irish Independent and the Fianna Fáil-aligned The Irish Press.

In later years, Smyllie’s health declines, prompting a quieter lifestyle. He moves from his large house in Pembroke Park, Dublin, to Delgany, County Wicklow. As he does not drive, he becomes less present in the newspaper office in D’Olier Street, contributing to a decline in the paper’s dynamism. His health deteriorates further, resulting in frequent absences from his editorial duties, though he retains his position despite management attempts to limit his authority, especially over finances. He dies of heart failure on September 11, 1954.

In 1925, Smyllie marries Kathlyn Reid, eldest daughter of a County Meath landowner. They have no children.

Smyllie is an eccentric: he hits his tee shots with a nine iron, speaks in a curious mix of Latin phrases and everyday Dublin slang, and weighs 22 stone (308 lbs.; 140 kg) yet still cycles to work wearing a green sombrero.