Waddell Cunningham, merchant and public figure in Georgian-era Belfast, dies at his restored house in Hercules Street (now Royal Avenue) in Belfast on December 15, 1797, seven months before the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

Cunningham is born in 1728 or 1729 at Ballymacilhoyle in the parish of Killead, County Antrim, the youngest son in the large family of John Cunningham and his wife, Jane, daughter of James Waddell of Islandderry, a townland in the parish of Dromore, County Down. The extended families of Cunningham and Waddell have interests in farming, linen, provisioning, and overseas trade. By 1752, no doubt with support from his family, Cunningham is in New York City trading near the meal market. Just as the Seven Years’ War is beginning in May 1757, he becomes the local partner of a Belfast merchant, Thomas Greg. While carrying on a wide range of commercial activities, the firm of Greg & Cunningham specialises in the flaxseed trade with Ireland and becomes “the most successful Irish American transatlantic trading partnership of the colonial period.” He amasses a large fortune from trade, some of it illicit, during the war, and becomes one of the largest shipowners in the American port. This enables the partners to purchase a 150-acre estate, which they rename “Belfast,” on the West Indies island of Dominica, just as it is passing, by the Treaty of Paris (1763), from French to British rule. It is possible that the estate is managed by Greg’s brother, John.

Sometime after suffering imprisonment for assaulting a fellow merchant (July–August 1763), Cunningham returns to Ireland, leaving the firm in the charge of junior partners until its dissolution in 1775. In Belfast he enters into a second partnership with Greg in May 1765 comprising all their business activities other than those in New York. In November 1765, he also marries Greg’s sister-in-law Margaret, second daughter of a Belfast merchant, Samuel Hyde. He lives in a large house in Hercules Street, later renamed Royal Avenue, which serves also as the premises for his many business interests, commercial, financial, industrial, and agricultural. In 1767, he and Greg start the manufacture of vitriol at a factory by the River Lagan at Lisburn, 12 km from Belfast. They open up fisheries in Donegal and Sligo, exporting herring to the West Indies as food for slaves. They also trade Irish horses and mules for West Indian sugar and American tobacco, the sugar being processed by them at the New Sugar House in Waring Street, Belfast. During the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), he illegally ships linen uniforms to the insurgent colonists. He becomes a middleman on the estate of Arthur Chichester, 5th Earl of Donegall, by obtaining leases of land in the Templepatrick district of County Antrim, a venture that involves him in disputes with tenant farmers resulting in an attack by the Hearts of Steel on Belfast and the destruction by fire of his home on December 23, 1771.

Despite this setback, Cunningham becomes the foremost Belfast merchant. As well as those mentioned, he has interests in shipping, brewing, glass manufacture and flour milling. When a chamber of commerce is set up in 1783, he is elected president, a position he holds until 1790. In the 1780s, in partnership with William Brown, John Campbell and Charles Ranken, he opens a bank. Known as Cunningham’s Bank, it closes on December 31, 1793, likely as a result of the recession brought on by the outbreak of war between England and France.

A prominent Volunteer, Cunningham joins the movement as a lieutenant in 1778 and is captain of the 1st Belfast company from 1780 until the dissolution of the Volunteers in 1793. Entering politics, he fails to be nominated as a parliamentary candidate for Belfast by its patron, Lord Donegall, at the general election of 1783, but stands for Carrickfergus at a February 1784 by-election on a platform of parliamentary reform and is returned – a rare distinction for a Presbyterian – by 474 votes to 289. A petition against his return is lodged successfully, but he remains an MP until March 1785, when he is defeated in a new election. It is during this period that he, probably the wealthiest, most enterprising merchant in Belfast and having, as he does, Caribbean interests, proposes in December 1784 fitting out a ship to engage in the Atlantic slave trade. The proposal comes to nothing but is the subject of intense debate in the 1920s between two rival Belfast local historians, Francis Joseph Bigger and Samuel Shannon Millin.

Cunningham plays a prominent role on several Belfast boards – those of White Linen Hall, the harbour, poorhouse, and dispensary. He gives money to the first Catholic chapel, St. Mary’s, opened in the town in 1784, and to the First Belfast Presbyterian congregation, as well as providing a site for a meeting house for his own congregation, Second Belfast, in 1767. Staunch in his advocacy of the reform of parliament, he becomes a member of the Northern Whig Club in 1790. He is cautious, however, about Catholic relief, for he fears its possible consequences. On July 14, 1792, an organiser of a Volunteer display to mark the third anniversary of the fall of the Bastille, he balks even at a very moderately worded resolution in favour of the Catholics. Thereafter he becomes increasingly ill-disposed toward reform and when the Belfast yeoman infantry is formed in 1797, he becomes captain of the 4th company.

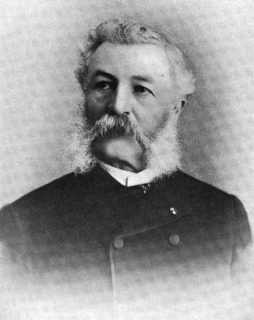

Cunningham dies on December 15, 1797, at his restored house in Hercules Street. He and his wife have no children. His property in Ireland (worth £60,000) passes to James Douglas, youngest son of his sister Jane, who had married their first cousin, Cunningham’s personal clerk Robert Douglas. His name had already passed to Thomas Greg’s son, Cunningham Greg, who takes over Greg’s business after his death. Cunningham’s portrait is painted by Robert Home. A mausoleum is built over the Cunningham vault at Knockbreda Church cemetery overlooking Belfast.

(From: “Cunningham, Waddell” by C. J. Woods, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)