Irish poet Paul Muldoon wins the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry on April 8, 2003, for his work Moy Sand and Gravel (2002). Additionally, he has published more than thirty collections and won the T. S. Eliot Prize. At Princeton University he has been both the Howard G. B. Clark ’21 University Professor in the Humanities and Founding Chair of the Lewis Center for the Arts. He holds the post of Professor of Poetry at the University of Oxford from 1999 to 2004 and has also served as president of The Poetry Society (UK) and poetry editor at The New Yorker.

Muldoon, the eldest of three children, is born on June 20, 1951, on a farm in County Armagh, Northern Ireland, outside The Moy, near the boundary with County Tyrone. His father works as a farmer (among other jobs) and his mother is a school mistress. In 2001, Muldoon says of the Moy:

“It’s a beautiful part of the world. It’s still the place that’s ‘burned into the retina,’ and although I haven’t been back there since I left for university 30 years ago, it’s the place I consider to be my home. We were a fairly non-political household; my parents were nationalists, of course, but it was not something, as I recall, that was a major area of discussion. But there were patrols; an army presence; movements of troops; and a sectarian divide. And that particular area was a nationalist enclave, while next door was the parish where the Orange Order was founded; we’d hear the drums on summer evenings. But I think my mother, in particular, may have tried to shelter us from it all. Besides, we didn’t really socialise a great deal. We were ‘blow-ins’ – arrivistes – new to the area, and didn’t have a lot of connections.”

Talking of his home life, Muldoon continues, “I’m astonished to think that, apart from some Catholic Truth Society pamphlets, some books on saints, there were, essentially, no books in the house, except one set, the Junior World Encyclopedia, which I certainly read again and again. People would say, I suppose that it might account for my interest in a wide range of arcane bits of information. At some level, I was self-educated.” He is a “Troubles poet” from the beginning.

In 1969, Muldoon reads English at Queen’s University Belfast (QUB), where he meets Seamus Heaney and becomes close to the Belfast Group of poets which include Michael Longley, Ciaran Carson, Medbh McGuckian and Frank Ormsby. He says of the experience, “I think it was fairly significant, certainly to me. It was exciting. But then I was 19, 20 years old, and at university, so everything was exciting, really.” He is not a strong student at QUB. He recalls, “I had stopped. Really, I should have dropped out. I’d basically lost interest halfway through. Not because there weren’t great people teaching me, but I’d stopped going to lectures, and rather than doing the decent thing, I just hung around.” During his time at QUB, his first collection New Weather (1973) is published by Faber & Faber. He meets his first wife, fellow student Anne-Marie Conway, and they are married after their graduation in 1973. The marriage breaks up in 1977.

For thirteen years (1973–86), Muldoon works as an arts producer for the BBC in Belfast. In this time, which sees the most bitter period of the Troubles, he published the collections Why Brownlee Left (1980) and Quoof (1983). After leaving the BBC, he teaches English and Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia and at Gonville and Caius College and Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, where his students include Lee Hall (Billy Elliot) and Giles Foden (The Last King of Scotland). In 1987, he emigrates to the United States, where he teaches in the creative writing program at Princeton University. He is Professor of Poetry at Oxford University for the five-year term 1999–2004, and is an Honorary Fellow of Hertford College, Oxford.

Muldoon has been awarded fellowships in the Royal Society of Literature and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the 1994 T. S. Eliot Prize, the 1997 The Irish Times Literature Prize for Poetry, and the 2003 Griffin International Prize for Excellence in Poetry. He is also shortlisted for the 2007 Poetry Now Award. His poems have been collected into four books: Selected Poems 1968–1986 (1986), New Selected Poems: 1968–1994 (1996), Poems 1968–1998 (2001) and Selected Poems 1968–2014 (2016). In September 2007, he is hired as poetry editor of The New Yorker.

Muldoon is married to novelist Jean Hanff Korelitz, whom he meets at an Arvon Foundation writing course. He has two children, Dorothy and Asher, and lives primarily in New York City.

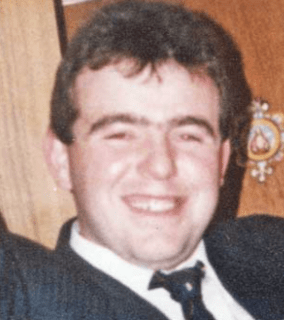

(Pictured: Paul Muldoon in Tepoztlán, Morelos, Mexico, 2018. Photograph by Alejandro Arras.)