Roger McCorley, Irish republican activist, is born into a Roman Catholic family at 67 Hillman Street in Belfast on September 6, 1901.

McCorley is one of three children born to Roger Edmund McCorley, a meat carver in a hotel, and Agnes Liggett. He has two elder brothers, Vincent and Felix. He joins the Fianna in his teens. His family has a very strong republican tradition, and he claims to be the great-grandson of the United Irishmen folk hero Roddy McCorley, who was executed for his part in the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

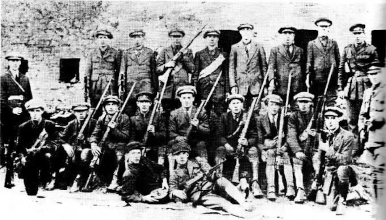

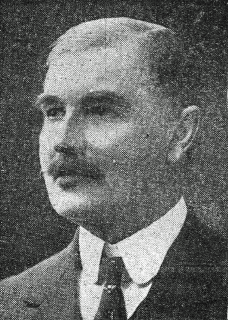

McCorley is a member of the Belfast Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Irish War of Independence (1919–1922). He is commandant of the Brigade’s first battalion, eventually becoming Commandant of the Belfast Brigade. In June 1920, he is involved in an attack on a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) police barracks at Crossgar, County Down. On Sunday, August 22, 1920, in Lisburn, he is involved in the assassination of RIC District Inspector Oswald Swanzy, who was held responsible by Michael Collins for the assassination of Tomás McCurtain, Lord Mayor of Cork.

McCorley is noted for his militancy, as he is in favour of armed attacks on British forces in Belfast. The Brigade’s leaders, by contrast, in particular, Joe McKelvey, are wary of sanctioning attacks for fear of loyalist reprisals on republicans and the Catholic population in general. In addition, McCorley is in favour of conducting an armed defense of Catholic areas, whereas McKelvey does not want the IRA to get involved in what he considers to be sectarian violence. McCorley writes later that in the end, “the issue settled itself within a very short space of time, when the Orange mob was given uniforms, paid for by the British, and called the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC).” The role of the USC, a temporary police force raised for counter-insurgency purposes, in the conflict is still debated, but republicans maintain that the organization was responsible for the indiscriminate killings of Catholics and nationalists.

On January 26, 1921, McCorley, is involved in the fatal shooting of three Auxiliary Division officers in their beds in the Railway View hotel in central Belfast. Shortly afterwards, he and another IRA man, Seamus Woods, organize an active service unit (ASU) within the first battalion of the Belfast Brigade, with the intention of carrying out attacks, with or without the approval of the Brigade leadership. The unit consists of 32 men. McCorley later writes, “I issued a general order that, where reprisal gangs [State forces] were cornered, no prisoners were to be taken.” In March 1921, he personally leads the ASU in the killing of three Black and Tans in Victoria Street in central Belfast. He is responsible for the deaths of two more Auxiliaries in Donegall Place in April. In reprisal for these shootings, members of the RIC assassinate two republican activists, the Duffin brothers in Clonard Gardens in west Belfast. On June 10, 1921, both and Woods and McCorley units are involved in the killing a RIC man who is suspected in the revenge killings of the Duffin brothers. Two RIC men and a civilian are also wounded in that attack.

Thereafter, there is what historian Robert Lynch has described as a “savage underground war” between McCorley’s ASU and RIC personnel based in Springfield Road barracks and led by an Inspector Ferris. Ferris is accused of murdering the Lord Mayor of Cork Thomas MacCurtain and had been posted to Lisburn for his safety. Ferris himself is among the casualties, being shot in the chest and neck, but surviving. McCorley claims to have been one of the four IRA men who shot Ferris. In addition, his men bomb and burn a number of businesses including several cinemas and a Reform Club. In May 1921, however, thirteen of his best men are arrested when surrounded by British troops during an operation in County Cavan. They are held in Crumlin Road Gaol and sentenced to death.

On June 3, McCorley organizes an attack on Crumlin Road Gaol in an attempt to rescue the IRA men held there before they are executed. The operation is not a success; however, the condemned men are reprieved after a truce is agreed between the IRA and British forces in July 1921. On Bloody Sunday (July 10, 1921), he is a major leader in the defense of nationalist areas from attacks by both the police and loyalists. On that day twenty people are killed before he negotiates a truce beginning at noon on July 11. At least 100 people are wounded, about 200 houses are destroyed or badly damaged – most of them Catholic homes, leaving 1,000 people homeless.

In April 1922, McCorley becomes leader of the IRA Belfast Brigade after Joe McKelvey goes south to Dublin to join other IRA members who are against the Anglo-Irish Treaty. With McKelvey’s departure, Seamus Woods becomes Officer Commanding of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division, which has up to 1,000 members, with McCorley designated as Vice Officer Commanding. McCorley for his part, supports the Treaty, despite the fact that it provides for the partition of Ireland and the continued British rule in Northern Ireland. The reason for this is that Michael Collins and Eoin O’Duffy have assured him that this is only a tactical move and indeed, Collins sends men, money and weapons to the IRA in the North throughout 1922.

However, McCorley’s command sees the collapse of the Belfast IRA. In May 1922, the IRA launches an offensive with attacks all across Northern Ireland. In Belfast, he carries out an assault on Musgrave Street RIC barracks. He also conducts an arson campaign on businesses in Belfast. His men also carry out a number of assassinations, including that of Ulster Unionist Party MP William J. Twaddell, which causes the internment of over 200 Belfast IRA men.

To escape from the subsequent repression, McCorley and over 900 Northern IRA men flee south, to the Irish Free State, where they are housed in the Curragh. McCorley is put in command of these men. In June 1922, the Irish Civil War breaks out between Pro and Anti-Treaty elements of the IRA. He takes the side of the Free State and Michael Collins. After Collins is killed in August 1922, his men are stood down. About 300 of them join the National Army and are sent to County Kerry to put down anti-Treaty guerrillas there. In the Spring of 1923, bitterly disillusioned by the brutal counterinsurgency against fellow republicans, he resigns his command.

McCorley later asserts that he “hated the Treaty” and only supported it because it allowed Ireland to have its own armed forces. Both he and Seamus Woods are severe critics of the Irish Free State inertia towards Northern Ireland after the death of Michael Collins. He comments that when Collins was killed “the Northern element gave up all hope.”

In 1936 McCorley is instrumental in the establishment of the All-Ireland Old IRA Men’s Organization, serving as Vice-President with President Liam Deasy (Cork No. 3 Brigade) and Secretary George Lennon (Waterford No. 2 Brigade).

In the 1940s, McCorley is a founding member of Córas na Poblachta, a political party which aspires to a United Ireland and economic independence from Britain. He dies on November 13, 1993, and is buried in the Republican Plot of Glasnevin Cemetery.