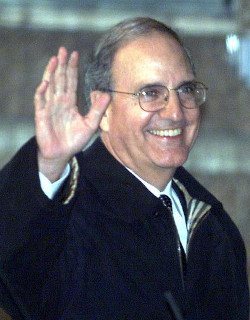

On June 10, 1996, former U.S. Senator George Mitchell begins Northern Ireland talks with Sinn Féin, who are blocked by the lack of an Irish Republican Army (IRA) ceasefire from what are supposed to be all-party talks on Northern Ireland’s future.

Pressure is coming from all sides on the Irish Republican Army to give peace a chance in Northern Ireland. Governments in London, Dublin, and Washington, D.C., as well as the vast majority of Northern Ireland’s citizens, are calling on the paramilitary group to call a new ceasefire. Even Gerry Adams, president of Sinn Féin, the IRA’s political wing, appeals to the IRA to reconsider its refusal to renew the ceasefire it broke in February with a bomb blast in London.

An opinion poll in the Dublin-based Sunday Tribune shows 97 percent of people, including 84 percent of Sinn Féin voters, want the IRA to renew its ceasefire.

The talks aim to reconcile two main political traditions in Northern Ireland, Protestant-backed unionism, which wants the province to stay part of the United Kingdom, and Catholic-backed Irish nationalism, which seeks to unite Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland.

Earlier in the year Senator Mitchell reported to the British government on the prospects for peace in Northern Ireland and drew up six principles which, if fulfilled by all the parties, would produce a lasting political settlement.

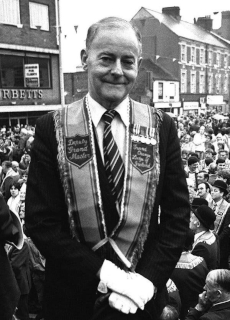

As internal and international pressure on the IRA mounts, politicians from the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), a moderate party representing the province’s Protestants, shows signs of drifting apart on whether Sinn Féin should be allowed to participate. Even if the IRA announces “a ceasefire of convenience,” Sinn Féin should be barred from attending, says Peter Robinson, deputy leader of the radical Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

Furthermore, the choice of Mitchell to head the talks makes some Protestants uneasy. Earlier, DUP leader Ian Paisley says Mitchell could not be trusted as chairman. “He is carrying too much American Irish baggage.”

Yet David Trimble, leader of the larger UUP, says a new IRA ceasefire might “get Sinn Féin to the door.” To be fully admitted to the all-party talks, however, its leadership will have to “commit itself to peace and democracy.” Trimble adds that he has doubts about Mitchell’s objectivity and had sought “certain assurances” before finally agreeing to lead a UUP delegation to the opening round. Mitchell, at an impromptu news conference in Belfast, says he plans to show “fairness and impartiality.”

The attitudes of the two unionist parties appear to reflect concern that the IRA would declare a ceasefire before the talks open, or during the early stages, technically clearing the way for Sinn Féin participation. David Wilshire, a senior Conservative member of Britain’s Parliament, who supports the unionist cause, says that a ceasefire by the IRA now would be a “cynical ploy.” He adds that “the government should not fall for it.”

Sinn Féin leaders, meanwhile, meet on Saturday, June 8, and announced that regardless of the IRA’s intentions, Adams and other Sinn Féin leaders will turn up at the opening session and demand to be admitted. They cite the party’s strong showing at special elections in May to the peace forum at which they obtain 15 percent of the vote and win a strong mandate from Catholic voters in West Belfast.

It is “the British government’s responsibility” to urge the IRA to renew its truce, says Martin McGuinness, Adams’s deputy. Yet Adams himself makes a direct approach to the IRA. This is confirmed by Albert Reynolds, the former Irish Taoiseach. He says that Adams has advised him that he is about to make a new ceasefire appeal to the IRA leadership. “I am now satisfied Gerry Adams and Sinn Féin will seek an early reinstatement of the ceasefire which, of course, has not broken down in Northern Ireland. I see a set of similar elements to those in 1994, which brought about the ceasefire, now coming together. Everyone must now compromise,” Reynolds says.

On June 8, the IRA tells the British Broadcasting Corporation that its military council has called a meeting to examine the agenda for the Northern Ireland talks.

(From:”Hopes for N. Ireland Talks Rely on Squeezing the IRA” by Alexander MacLeod, The Christian Science Monitor, June 10, 1996)