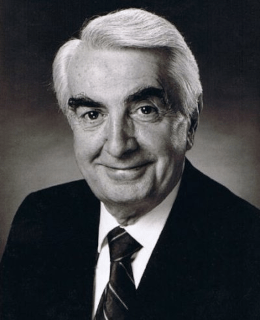

Tony Gregory, Irish independent politician and a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Dublin Central constituency from 1982 to 2009, dies in Dublin on January 2, 2009.

Gregory is born on December 5, 1947, in Ballybough on Dublin’s Northside, the second child of Anthony Gregory, warehouseman in Dublin Port, and Ellen Gregory (née Judge). He wins a Dublin Corporation scholarship to the Christian Brothers’ O’Connell School. He later goes on to University College Dublin (UCD), where he receives a Bachelor of Arts degree and later a Higher Diploma in Education, funding his degree from summer work at the Wall’s ice cream factory in Acton, London. Initially working at Synge Street CBS, he later teaches history and French at Coláiste Eoin, an Irish language secondary school in Booterstown. His students at Synge Street and Coláiste Eoin include John Crown, Colm Mac Eochaidh, Aengus Ó Snodaigh and Liam Ó Maonlaí.

Gregory becomes involved in republican politics, joining Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in 1964. In UCD he helps found the UCD Republican Club, despite pressure from college authorities, and becomes involved with the Dublin Housing Action Committee. Within the party he is a supporter of Wicklow Republican Seamus Costello. Costello, who is a member of Wicklow County Council, emphasises involvement in local politics and is an opponent of abstentionism. Gregory sides with the Officials in the 1970 split within Sinn Féin. Despite having a promising future within the party, he resigns in 1972 citing frustration with ideological infighting in the party. Later, Costello, who had been expelled by Official Sinn Féin, approaches him and asks him to join his new party, the Irish Republican Socialist Party. He leaves the party after Costello’s assassination in 1977. He is briefly associated with the Socialist Labour Party.

Gregory contests the 1979 local elections for Dublin City Council as a “Dublin Community Independent” candidate. At the February 1982 general election, he is elected to Dáil Éireann as an Independent TD. On his election he immediately achieves national prominence through the famous “Gregory Deal,” which he negotiates with Fianna Fáil leader Charles Haughey. In return for supporting Haughey as Taoiseach, he is guaranteed a massive cash injection for his inner-city Dublin constituency, an area beset by poverty and neglect.

Although Gregory is reviled in certain quarters for effectively holding a government to ransom, his uncompromising commitment to the poor is widely admired. Fianna Fáil loses power at the November 1982 general election, and many of the promises made in the Gregory Deal are not implemented by the incoming Fine Gael–Labour Party coalition.

Gregory is involved in the 1980s in tackling Dublin’s growing drug problem. Heroin had largely been introduced to Dublin by the Dunne criminal group, based in Crumlin, in the late 1970s. In 1982 a report reveals that 10% of 15- to 24-year-olds have used heroin at least once in the north inner city. The spread of heroin use also leads to a sharp increase in petty crime. He confronts the government’s handling of the problem as well as senior Gardaí, for what he sees as their inadequate response to the problem. He co-ordinates with the Concerned Parents Against Drugs group in 1986, who protest and highlight the activities of local drug dealers and defend the group against accusations by government Ministers Michael Noonan and Barry Desmond that it is a front for the Provisional IRA. He believes that the solution to the problem is multi-faceted and works on a number of policy level efforts across policing, service co-ordination and rehabilitation of addicts. In 1995 in an article in The Irish Times, he proposes what would later become the Criminal Assets Bureau, which is set up in 1996, catalysed by the death of journalist Veronica Guerin. His role in its development is later acknowledged by then Minister for Justice Nora Owen.

Gregory also advocates for Dublin’s street traders. After attending a sit-down protest with Sinn Féin Councillor Christy Burke, and future Labour Party TD Joe Costello on Dublin’s O’Connell Street in defence of a street trader, he, Burke and four others are arrested and charged with obstruction and threatening behaviour. He spends two weeks in Mountjoy Prison after refusing to sign a bond to keep the peace.

Gregory remains a TD from 1982 and, although he never holds a government position, remains one of the country’s most recognised Dáil deputies. He always refuses to wear a tie in the Dáil chamber stating that many of his constituents could not afford them.

Gregory dies on January 2, 2009, following a long battle with cancer. Following his death, tributes pour in from politicians from every party, recognising his contribution to Dublin’s north inner city. During his funeral, politicians from the Labour Party, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael are told that although they speak highly of Gregory following his death, during his time in the Dáil he had been excluded by many of them and that they were not to use his funeral as a “photo opportunity.” He is buried on January 7, with the Socialist Party‘s Joe Higgins delivering the graveside oration.

Colleagues of Tony Gregory support his election agent, Dublin City Councillor Maureen O’Sullivan, at the 2009 Dublin Central by-election in June. She wins the subsequent by-election.