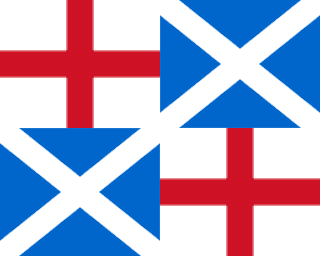

The Tender of Union, a declaration of the Parliament of England during the Interregnum following the War of the Three Kingdoms, comes into effect on April 12, 1654. The ordinance states that Scotland will cease to have an independent parliament and will join England in its emerging Commonwealth republic.

The English parliament passes the declaration on October 28, 1651 and after a number of interim steps an Act of Union is passed on June 26, 1657. The proclamation of the Tender of Union in Scotland on February 4, 1652 regularises the de facto annexation of Scotland by England at the end of the Third English Civil War. Under the terms of the Tender of Union and the final enactment, the Scottish Parliament is permanently dissolved and Scotland is given 30 seats in the Westminster Parliament. This act like all the others passed during the Interregnum is repealed by both Scottish and English parliaments upon the Restoration of monarchy under Charles II.

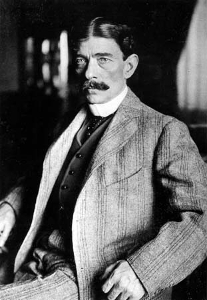

On October 28, 1651 the English Parliament issues the Declaration of the Parliament of the Commonwealth of England, concerning the Settlement of Scotland, in which it is stated that “Scotland shall, and may be incorporated into, and become one Common-wealth with this England.” Eight English commissioners are appointed, Oliver St. John, Sir Henry Vane, Richard Salwey, George Fenwick, John Lambert, Richard Deane, Robert Tichborne, and George Monck, to further the matter. The English parliamentary commissioners travel to Scotland and at Mercat Cross, Edinburgh on February 4, 1652, proclaim that the Tender of Union is in force in Scotland. By April 30, 1652 the representatives of the shires and Royal burghs of Scotland have agreed to the terms which include an oath that Scotland and England be subsumed into one Commonwealth. On the April 13, 1652, between the proclamation and the last of the shires to agree to the terms, a bill for an Act for incorporating Scotland into one Commonwealth with England is given a first and a second reading in the Rump Parliament but it fails to return from its committee stage before the Rump is dissolved. A similar act is introduced into the Barebone’s Parliament but it too fails to be enacted before that parliament is dissolved.

On April 12, 1654, the Ordinance for uniting Scotland into one Commonwealth with England is issued by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell and proclaimed in Scotland by the military governor of Scotland, General George Monck. The Ordinance does not become an Act of Union until it is approved by the Second Protectorate Parliament on June 26, 1657 in an act that enables several bills.