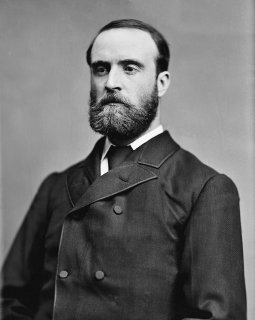

Patrick Ford, Irish American journalist, Georgist land reformer and fund-raiser for Irish causes, is born in Galway, County Galway on April 12, 1837.

Ford is born to Edward Ford (1805-1880) and Ann Ford (1815-1893), emigrating with his parents to Boston, Massachusetts in 1845, never returning to Ireland. He writes in the Irish World in 1886 that “I might as well have been born in Boston. I know nothing of England. I brought nothing with me from Ireland — nothing tangible to make me what I am. I had consciously at least, only what I found and grew up with in here.”

Ford leaves school at the age of thirteen and two years later is working as a printer’s devil for William Lloyd Garrison‘s The Liberator. He credits Garrison for his advocacy for social reform. He begins writing in 1855 and by 1861 is editor and publisher of the Boston Tribune, also known as the Boston Sunday Tribune or Boston Sunday Times. He is an abolitionist and pro-union.

During the American Civil War (1861–1865) Ford serves in the Union Army in the Ninth Massachusetts Regiment with his father and brother. He sees action in northern Virginia and fights in the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Ford spends four years after the war in Charleston, South Carolina, editing the Southern Carolina Leader, printed to support newly freed slaves. He settles in New York City in 1870 and founds the Irish World, which becomes the principal newspaper of Irish America. It promises “more reading material than any other paper in America” and outsells John Boyle O’Reilly‘s The Pilot.

In 1878, Ford re-titles his newspaper, the Irish World and American Industrial Liberator. During the early 1880s, he promotes the writings of land reformer, Henry George in his paper.

In 1880, Ford begins to solicit donations through the Irish World to support Irish National Land League activities in Ireland. Funds received are tabulated weekly under the heading “Land League Fund.” Between January and September 1881 alone, more than $100,000 is collected in donations. British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone later states that without the funds from the Irish World, there would have been no agitation in Ireland.”

Patrick Ford dies on September 23, 1913.