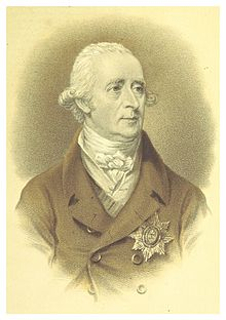

Sir Eyre Coote, Irish-born British soldier and politician who serves as Governor of Jamaica, is born on May 20, 1759.

Coote is the second son of the Very Reverend Charles Coote of Shaen Castle, Queen’s County (now County Laois), Dean of Kilfenora, County Clare, and Grace Coote (née Tilson). Educated at Eton College (1767–71), he enters Trinity College Dublin (TCD) on November 1, 1774, but does not graduate. In 1776 he is commissioned ensign in the 37th (North Hampshire) Regiment of Foot and carries the regiment’s colours at the Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War. He fights in several of the major battles in the war, including Rhode Island (September 15, 1776), Brandywine (September 11, 1777) and the siege of Charleston (1780). He serves under Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, in Virginia and is taken prisoner during the siege of Yorktown in October 1781.

On his release Coote returns to England, is promoted major in the 47th (Lancashire) Regiment of Foot in 1783, and in 1784 inherits the substantial estates of his uncle Sir Eyre Coote. He inherits a further £200,000 by remainder on his father’s death in 1796. He resides for a time at Portrane House, Maryborough, Queen’s County, and is elected MP for Ballynakill (1790–97) and Maryborough (1797–1800). Although he opposes the union, he vacates his seat to allow his elder brother Charles, 2nd Baron Castle Coote, to return a pro-union member. He serves with distinction in the West Indies (1793–95), particularly at the storming of Guadeloupe on July 3, 1794, and becomes colonel of the 70th (Surrey) Regiment of Foot (1794), aide-de-camp to King George III (1795), and brigadier-general in charge of the camp at Bandon, County Cork (1796).

Coote is active in suppressing the United Irishmen in Cork throughout 1797, and in June arrests several soldiers and locals suspected of attempting to suborn the Bandon camp. On January 1, 1798, he is promoted major-general and given the command at Dover. He leads the expedition of 1,400 men that destroy the canal gates at Ostend on May 18, 1798, holding out stubbornly for two days against superior Dutch forces until he is seriously wounded and his force overwhelmed. Taken prisoner, he is exchanged and in 1800 commands a brigade in Sir Ralph Abercromby‘s Mediterranean campaign, distinguishing himself at Abu Qir and Alexandria. For his services in Egypt, he receives the thanks of parliament, is made a Knight of the Bath, and is granted the Crescent by the Sultan.

In 1801 Coote returns to Ireland. Elected MP for Queen’s County (1802–06), he generally supports the government and is appointed governor of the fort of Maryborough. He gives the site and a large sum of money towards the building of the old county hospital in Maryborough. In 1805 he is promoted lieutenant-general, and he serves as lieutenant-governor of Jamaica (1806–08). His physical and mental health deteriorates in the West Indian climate, and he is relieved of his post in April 1808. He is second in command in the Walcheren Campaign of 1809 and leads the force that takes the fortress of Flushing. However, he shows signs of severe stress during the campaign and asks to be relieved from command because his eldest daughter is seriously ill.

Coote is conferred LL.D. at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1811. Elected MP for Barnstaple, Devon (1812–18), he usually votes with government, but opposes them by supporting Catholic emancipation, claiming that Catholics strongly deserve relief because of the great contribution Catholic soldiers had made during the war. He strongly opposes the abolition of flogging in the army. Despite a growing reputation for eccentricity, he is promoted full general in 1814 and appointed Knight Grand Cross (GCB) on January 2, 1815, but his conduct becomes increasingly erratic. In November 1815 he pays boys at Christ’s Hospital school, London, to allow him to flog them and to flog him in return. Discovered by the school matron, he is charged with indecent behaviour. The Lord Mayor of London dismisses the case and Coote donates £1,000 to the school, but the scandal leads to a military inquiry on April 18, 1816. Although it is argued that his mind had been affected by the Jamaican sun and the deaths of his daughters, the inquiry finds that he is not insane and that his conduct is unworthy of an officer. Despite the protests of many senior officers, he is discharged from the army and deprived of his honours.

Coote continues to decline and dies in London on December 10, 1823. He is buried at his seat of West Park, Hampshire, where in 1828 a large monument is erected to him and his uncle Sir Eyre Coote.

Coote first marries Sarah Robard in 1785, with whom he has three daughters, all of whom die young of consumption. Secondly, he marries in 1805, Katherine, daughter of John Bagwell of Marlfield, County Tipperary, with whom he has one son, his heir Eyre Coote III, MP for Clonmel (1830–33). He also has a child by Sally, a slave girl in Jamaica, from whom Colin Powell, United States Army general and Secretary of State, claims descent.