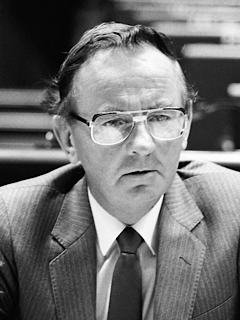

Richard Ryan, Fine Gael politician, is born in Dublin on February 27, 1929. He serves as Minister for Finance and Minister for the Public Service from 1973 to 1977 and a Member of the European Court of Auditors from 1986 to 1989. He serves as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 1977 to 1986. He serves as a Teachta Dála (TD) from 1959 to 1982.

Ryan is educated at Synge Street CBS, University College Dublin (UCD), where he studies economics and jurisprudence, and the Law Society of Ireland, subsequently qualifying as a solicitor. A formidable orator, at UCD he is auditor of the Literary and Historical Society (L&H) and subsequently of the Solicitors Apprentice Debating Society (1950), and wins both societies’ gold medals for debating. He serves as an Honorary Vice-president of the L&H.

After qualifying, Ryan works for several solicitors’ firms before establishing a private practice in Dame Street in Dublin, in which he remains an active partner until appointed to ministerial office in 1973.

Ryan first holds political office when he is elected to Dáil Éireann as a Fine Gael TD for Dublin South-West in a 1959 by-election, and retains his seat until he retires at the February 1982 Irish general election to concentrate on his European Parliament seat.

In opposition, Ryan serves as Fine Gael Spokesperson on Health and Social Welfare (1966–70) and on Foreign Affairs and Northern Ireland (1970–73). During this period he is involved in several important pro bono legal cases, including the 1963 challenge in the High Court, and then, on appeal, in the Supreme Court of Ireland in 1964, by Gladys Ryan (no relation) on the constitutionality of the fluoridation of the water supply. While the court rules against Gladys Ryan, the case remains a landmark, for it establishes the right to privacy under the Constitution of Ireland (or, perhaps more precisely, the right to bodily integrity under Article 40.3.1.). The case also raises a legal controversy, owing to the introduction by Justice Kenny of the concept of unenumerated rights. Other notable cases involving Ryan include a challenge to the rules governing the drafting of constituency boundaries, and an unsuccessful attempt to randomise the order of candidates on ballot papers (owing to a preponderance of TDs with surnames from the first part of the alphabet).

Fine Gael comes to power in a coalition with the Labour Party in 1973, and Ryan becomes Minister for Finance. He presides over a tough four years in the National Coalition under Liam Cosgrave, during the 1970s oil crisis when, in common with most Western economies, Ireland faces a significant recession. He is variously lampooned as “Richie Ruin” on the Irish satire show Hall’s Pictorial Weekly, and as “Red Richie” for his government’s introduction of a wealth tax. Following the 1977 Irish general election Fine Gael is out of power, and he once again becomes Spokesperson on Foreign Affairs.

Ryan also served as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) in 1973 and from 1977 to 1979, being appointed to Ireland’s first delegation and third delegation. At the first direct elections to the European Parliament in 1979, he is elected for the Dublin constituency and is re-elected in 1984 European Parliament election in Ireland, heading the poll on both occasions.

On being appointed to the European Court of Auditors in 1986, he resigns his seat and is succeeded by Chris O’Malley. He serves as a member of the Court of Auditors from 1986 to 1994, being replaced by Barry Desmond. After retirement, he continues in several roles, including as a Commissioner of Irish Lights (until 2004) and a time as Chairman of the Irish Red Cross in 1998.

Ryan is the father of the economist and academic Cillian Ryan. He dies in Dublin at the age of 90 on March 17, 2019. He is buried at Newlands Cross Cemetery and Crematorium in Dublin.