On February 17, 1978, a British Army Aérospatiale Gazelle helicopter, serial number XX404, goes down near Jonesborough, County Armagh, Northern Ireland, after being fired at by a Provisional Irish Republican Army unit from the South Armagh Brigade. The IRA unit is involved at the time in a gun battle with a Royal Green Jackets observation post deployed in the area, and the helicopter is sent in to support the ground troops. The helicopter crashes after the pilot loses control of the aircraft while evading ground fire.

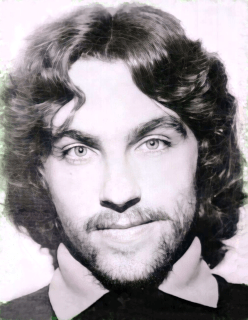

Lieutenant Colonel Ian Douglas Corden-Lloyd, 2nd Battalion Green Jackets commanding officer, dies in the crash. The incident is overshadowed in the press by the La Mon restaurant bombing, which takes place just hours later near Belfast.

By early 1978, the British Army forces involved in Operation Banner have recently replaced their aging Bell H-13 Sioux helicopters for the more versatile Aérospatiale Gazelles. The introduction of the new machines increases the area covered on a reconnaissance sortie as well as the improved time spent in airborne missions. In the same period, the Provisional IRA receives its first consignment of M60 machine guns from the Middle East, which are displayed by masked volunteers during a Bloody Sunday commemoration in Derry. Airborne operations are crucial for the British presence along the border, especially in south County Armagh, where the level of IRA activity means that every supply and soldier has to be ferried in and out of their bases by helicopter since 1975.

The Royal Green Jackets have been in South Armagh since December 1977, and have already seen some action. Just a few days after arrival, two mortar rounds hit the C Company base at Forkhill, injuring a number of soldiers. In the aftermath of the attack, two Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) officers are wounded by a booby trap while recovering the lorry where the mortar tubes are mounted. Two days later, a patrol near the border suffers a bomb and gun attack, leaving the commanding sergeant with severe head wounds. The sergeant is picked up from the scene by helicopter. He is later invalided from the British Army as a result of his injuries.

On January 17, 1978, a Royal Green Jackets observation post deployed around the village of Jonesborough begins to take heavy fire from the “March Wall,” which draws parallel with the Irish border to the east, along the Dromad woods. The soldiers return fire, but the short distance to the border and the open ground prevents them from advancing.

The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Ian Corden-Lloyd, along with Captain Philip Schofield and Sergeant Ives fly from the battalion base at Bessbrook Mill to assess the situation and provide information to the troops. They are escorted by a Scout helicopter with an Airborne Reaction Force (ARF), comprising a medic and three soldiers from the 2nd Battalion Light Infantry. While hovering over the scene of the engagement, the Aérospatiale Gazelle receives a barrage of 7.62 mm tracer rounds. The pilot loses control of the aircraft during a turn at high speed to avoid the stream of fire. The Aérospatiale Gazelle hits a wall and crashes in a field, some 2 km from Jonesborough. According to the crew and passengers of the Scout, the Aérospatiale Gazelle hits the ground twice after losing power, with its rotor blades trashing into the soil following the second impact, and then cartwheels across the field. The Scout lands the ARF while still under IRA fire. The soldiers rush to the wrecked helicopter, some 100 metres away from the site of the initial crash.

Corden-Lloyd is killed and the other two passengers are wounded. The machine comes to rest on its right side. The pilot remains trapped inside the wreckage, but he survives thanks to his helmet. The IRA later claim they had shot at the helicopter with an M60 machine gun. The IRA unit vanishes into the Dromad woods to the Republic of Ireland. Some Gardaí witness the attack from the other side of the border.

The gun battle and Aérospatiale Gazelle shootdown is displaced from the headlines by the deaths of twelve civilians in the La Mon restaurant bombing on the same day, some of whom are burned to death. Initially the British Army downplays the IRA’s claim as published by An Phoblacht, that the helicopter was shot down, on the basis that no hits were found on the wreckage, but finally they acknowledged that the IRA action had caused the crash.

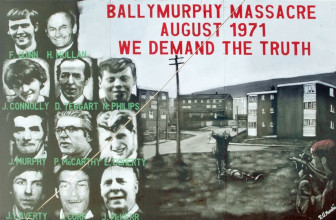

The death of Corden-Lloyd, a former Special Air Service officer, is deeply regretted by the British Army, who regarded him as promising. He is awarded a posthumous mentioned in despatches “in recognition of gallant and distinguished service in Northern Ireland.” In 1973, Irish republicans had accused Corden-Lloyd and his subordinates of brutality against Belfast Catholics during an earlier tour of the Royal Green Jackets in 1971, at the time of Operation Demetrius.