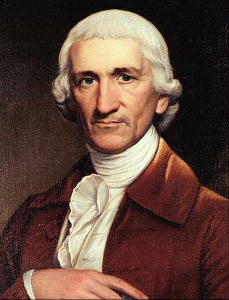

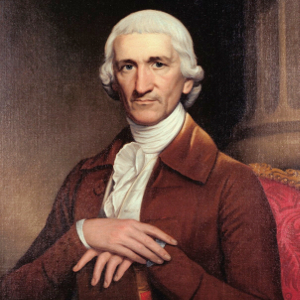

Charles Thomson, Irish-born Patriot leader in Philadelphia during the American Revolution and the secretary of the Continental Congress (1774–1789) throughout its existence, dies in Lower Merion Township, Pennsylvania, on August 16, 1824.

Thomson is born in Gorteade townland, Maghera parish, County Londonderry, to Scots Irish parents. After the death of his mother in 1739, his father emigrates to the British colonies in America with Charles and his brothers. His father dies at sea and the penniless boys are separated in America. Charles is cared for by a blacksmith in New Castle, Delaware, and is educated in New London Township, Pennsylvania. In 1750 he becomes a tutor in Latin at the Philadelphia Academy.

During the French and Indian War, Thomson is an opponent of the Pennsylvania proprietors’ American Indian policies. He serves as secretary at the Treaty of Easton (1758) and writes An Enquiry into the Causes of the Alienation of the Delaware and Shawanese Indians from the British Interest (1759), which blames the war on the proprietors. He is allied with Benjamin Franklin, the leader of the anti-proprietary party, but the two men part politically during the Stamp Act crisis in 1765. Thomson becomes a leader of Philadelphia’s Sons of Liberty. He is married to the sister of Benjamin Harrison V, another signer, as delegate, of the Declaration of Independence.

Thomson is a leader in the revolutionary crisis of the early 1770s. John Adams calls him the “Samuel Adams of Philadelphia.” Thomson serves as the secretary of the Continental Congress through its entirety. Through those 15 years, the Congress sees many delegates come and go, but Thomson’s dedication to recording the debates and decisions provides continuity. Along with John Hancock, president of the Congress, Thomson’s name (as secretary) appears on the first published version of the Declaration of Independence in July 1776.

Thomson’s role as secretary to Congress is not limited to clerical duties. Thomson is also noted for designing, with William Barton, the Great Seal of the United States. The Great Seal plays a prominent role in the January 14, 1784, ratification of the Treaty of Paris (1783). Britain’s representatives in Paris initially dispute the placement of the Great Seal and Congressional President Thomas Mifflin‘s signature, until mollified by Benjamin Franklin.

But Thomson’s service is not without its critics. James Searle, a close friend of John Adams, and a delegate, begins a cane fight on the floor of Congress against Thomson over a claim that he is misquoted in the “Minutes” that results in both men being slashed in the face. Such brawls on the floor are not uncommon, and many of them are promoted by argument over Thomson’s recordings. Political disagreements prevent Thomson from getting a position in the new government created by the United States Constitution. Thomson resigns as secretary of Congress in July 1789 and hands over the Great Seal, bringing an end to the Continental Congress.

Thomson spends his final years at Harriton House in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania working on a translation of the Bible. He also publishes a synopsis of the four evangelists in 1815. In retirement, Thomson also pursues his interests in agricultural science and beekeeping. According to Thomas Jefferson, writing to John Adams, Thomson becomes senile in his old age, unable to recognize members of his own household.