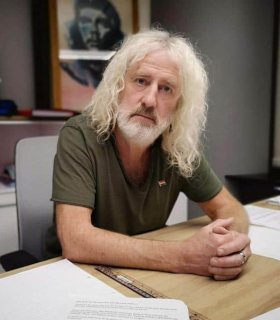

Michael “Mick” Wallace, former property developer and Irish politician who has been a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from Ireland for the South constituency since July 2019, is born in Wellingtonbridge, County Wexford, on November 9, 1955. He is considered to be one of the most eccentric and unconventional figures in Irish national politics.

Wallace is born into a family of twelve children. He graduates from University College Dublin (UCD) with a teaching qualification. He marries Mary Murphy from Duncormick, County Wexford, in 1979. The couple has two sons, but the marriage ends when the children are young. He has two more children from another relationship in the 1990s.

In 2007, Wallace founds the Wexford Football Club which he manages for their first three seasons and is chairman of its board. The club is in the League of Ireland First Division.

Prior to entering politics, Wallace owns a property development and construction company completing developments such as the Italian Quarter in the Ormond Quay area of the Dublin quays. The company later collapses into liquidation, with him finally being declared bankrupt on December 19, 2016.

On February 5, 2011, while a guest on Tonight with Vincent Browne, Wallace makes the announcement that he intends to contest the upcoming February 25 general election as an Independent candidate. He tops the poll in the Wexford constituency with 13,329 votes.

On December 15, 2011, Wallace helps to launch a nationwide campaign against the household charge which is introduced as part of the 2012 Budget.

Wallace is the listed officer of the Independents 4 Change, which is registered to stand for elections in March 2014 and, along with Clare Daly, is one of two MEPs which represent the party in the European parliament. During their time in the Dáil, Wallace and Daly, the Dublin North TD, become friends and political allies, and work together on many campaigns, including opposition to austerity and highlighting revelations of alleged Garda malpractices, including harassment, improper cancellation of penalty points and involvement of officers in the drug trade. They are partially active in protesting the Garda whistleblower scandal, which eventually leads to the resignation of Minister for Justice Frances Fitzgerald, although she is later cleared of wrongdoing by the Charleton Tribunal.

In July 2014, Wallace and Daly are arrested at Shannon Airport while trying to board a U.S. military aircraft. He says the airport is being used as a U.S. military base and that the government should be searching the planes to ensure that they are not involved in military operations or that there are no weapons on board. He is fined €2,000 for being in an airside area without permission and chooses not to pay. He is sentenced to 30 days in prison in default, and in December 2015 is arrested for non-payment of the fine.

In December 2015, Wallace and independent TDs Clare Daly and Maureen O’Sullivan each put forward offers of a €5,000 surety for a man charged with membership of an unlawful organisation and with possession of a component part of an improvised explosive device.

At the 2016 Irish general election, Wallace stands as an Independents 4 Change candidate and is re-elected, finishing third on the first-preference count with 7,917 votes.

In 2017, Wallace calls on Ireland to join the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement against Israel and “condemn the illegal expansion of Israeli settlements on Palestinian lands as well as the ongoing human rights abuses against Palestinians.”

At the 2019 European Parliament election, Wallace is elected as an MEP for the South constituency.

Wallace is criticised for supporting Venezuela, Ecuador, China, Russia, Belarus and Syria during his period as an MEP. In November 2020, he refers to Belarusian opposition presidential candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya as a “pawn of western neoliberalism.” In February 2021, he is reprimanded for using a swear word during a session of the European Parliament. He has referred to Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó as being an “unelected gobshite.”

In April 2021, Wallace and Daly are called “embarrassments to Ireland” by Fianna Fáil‘s Malcolm Byrne after the two MEPs had travelled to Iraq and visited the headquarters of the Popular Mobilization Forces, an Iraqi militia supported by Iran.

Wallace questions the director general of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), Fernando Arias, in the European Parliament in April 2021. He accuses the OPCW of falsely blaming the government of Bashar al-Assad for the 2018 Douma chemical attack. He says that, while he does not know what had happened in Douma, the White Helmets were “paid for by the U.S. and UK to carry out regime change in Syria.” Fianna Fáil’s Barry Andrews calls his accusation against the White Helmets a conspiracy theory and disinformation. French MEP Nathalie Loiseau describes his comments as “fake news” and apologises on his behalf to NGO groups in Syria.

In June 2021, Wallace and Daly are among the MEPs censured by the European Parliament’s Democracy Support and Election Coordination Group for acting as unofficial election-monitors in the December 2020 Venezuelan parliamentary election and April 2021 Ecuadorian general election without a mandate or permission from the EU. They are barred from making any election missions until the end of 2021. They are warned that any further such action may result in their ejection from the European parliament under the end of their terms in 2024.

Wallace has stated his opposition to vaccination certificates. He says, “I’m not anti-vax but we’re going down a dangerous path with COVID pass” and expresses concerns about civil liberties. Both Wallace and Daly have refused to present vaccination certs upon entering the European Parliament, resulting in them being reprimanded by the European Parliament.

In April 2022, Wallace and Daly initiate defamation proceedings against RTÉ.

On September 15, 2022, Wallace is one of sixteen MEPs who vote against condemning President Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua for human rights violations, in particular the arrest of Bishop Rolando José Álvarez Lagos.

In November 2022, Wallace criticises protests in Iran following the death of Mahsa Amini, accusing some protestors of violence and destruction and saying it “would not be tolerated anywhere.”

In February 2023, Wallace claims on social media that he has “three wine bars in Dublin.” This arouses alarm from his European parliamentary group, as no such assets were listed on his mandatory declaration of financial interests. After the chair of his parliamentary group calls any omission from the declaration “unacceptable” and not “worthy of our political group,” he amends his declaration to state that he is an “advisor” to the three wine bars and receives up to €500 a month in income for this role.