Sinéad Moira Cusack, award winning Irish actress, is born Jane Moira Cusack in Dalkey, County Dublin, on February 18, 1948.

Cusack is the daughter of actress Maureen Cusack and actor Cyril Cusack. She is the sister of actresses Sorcha Cusack, Niamh Cusack, and half-sister to Catherine Cusack. Her father is born in South Africa, to an Irish father and an English mother, and had worked with Micheál Mac Liammóir at Dublin‘s Gate Theatre.

Cusack’s first acting roles are at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. In 1975, she moves to London and joins the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) starring in Dion Boucicault‘s London Assurance in the West End. Her work with the RSC continues with an award-winning performance as Celia in As You Like It which includes the Clarence Derwent Award and her first Laurence Olivier Award nomination. She secures a second Olivier Award nomination for her performance in The Maid’s Tragedy by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher in 1981, followed two years later with a third Olivier Award nomination as Kate in The Taming of the Shrew.

Cusack makes her Broadway debut in 1984 performing in repertory with the Royal Shakespeare Company. Starring opposite Derek Jacobi, she plays Roxane in Anthony Burgess‘s translation of Edmond Rostand‘s Cyrano de Bergerac and Beatrice in William Shakespeare‘s Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Terry Hands. Much Ado is first produced at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1982–83, then moves to London’s Barbican Centre for the 1983–1984 season where it is joined by Cyrano, before both plays transfer to New York‘s Gershwin Theatre from October 1984 to January 1985, for which Cusack received a Tony Awards nomination for her performance as Beatrice, and costar Derek Jacobi wins the award for his Benedick. The production of Cyrano de Bergerac is later filmed in 1985.

During this period, Cusack and her husband, Jeremy Irons, appear in a Shakespeare Winter’s Eve, a major fundraiser for the Riverside Shakespeare Company in New York, along with other members of the Royal Shakespeare Company. Following the Broadway run, the plays tour the United States, making stops in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. Her connection with the Royal Shakespeare Company continues with a series of leading roles include Portia in The Merchant of Venice opposite David Suchet, Lady Macbeth opposite Jonathan Pryce in Macbeth and Cleopatra in Antony and Cleopatra in Stratford-upon-Avon and at London’s Theatre Royal Haymarket in the West End.

In 1990, Cusack, in the role of Masha, joins two of her sisters, Niamh (as Irina) and Sorcha (as Olga), and her father, Cyril Cusack (as Chebutykin) for a well-received production of Anton Chekhov‘s tragicomedy Three Sisters in a new version by Frank McGuinness, directed by Adrian Noble at the Gate Theatre, Dublin, before transferring to the Royal Court Theatre in London. The production also features Niamh’s husband, Finbar Lynch, as Solenyi and Lesley Manville as Natasha. The production wins the three real-life sisters the Irish Life Award in 1992.

One of Cusack’s best known stage roles is Our Lady of Sligo by Sebastian Barry in 1998, in which she plays the principal role of Mai O’Hara in performances in Ireland, on Broadway and at the National Theatre. For this she wins the 1998 Evening Standard Theatre Award for Best Actress, the 1998 Critics’ Circle Theatre Award for Best Actress and her fourth Olivier Award nomination for Best Actress. In 2006-07 she stars with Rufus Sewell in Tom Stoppard‘s Rock ‘n’ Roll at the Royal Court Theatre in London which transfers to the West End and Broadway, winning Cusack her fifth Olivier Award nomination and her second Tony Award nomination.

In 2015, Cusack returns to Ireland’s Abbey Theatre, where she begins her theatre career. She appears in the world première of Mark O’Rowe‘s play Our Few and Evil Days, acting opposite long-time collaborator Ciarán Hinds. She wins the Irish Times Irish Theatre Award for Best Actress.

Cusack stars with Peter Sellers in the film Hoffman (1970). She guest stars in an episode of The Persuaders! (1971), a TV series starring Tony Curtis and Roger Moore, as Jenny Lindley, a wealthy heiress who suspects that a man claiming to be her dead brother is in fact an impostor. In 1975, she makes three appearances in the TV series Quiller as the character Roz.

Cusack and her husband appear together in the film Waterland (1992), in a television adaptation of Christopher Hampton‘s Tales from Hollywood (also 1992), and again in Bernardo Bertolucci‘s Stealing Beauty (1996). Further film work includes Passion of Mind (2000), V for Vendetta (2005), and Eastern Promises (2007), a thriller directed by David Cronenberg. Her performance in The Tiger’s Tail (2007) wins her a first Irish Film & Television Academy (IFTA) Award nomination for Best Actress in a Supporting Role. She wins the IFTA Award for her performance in The Sea (2013), adapted from the novel by John Banville. She is nominated once more for an IFTA Award for her performance in John Boorman‘s drama film Queen and Country (2014), which premières at the Cannes Film Festival.

Further starring roles include lead roles in Oliver’s Travels (1995), Have Your Cake and Eat It (1997) for which Cusack wins the Royal Television Society‘s RTS Award for Best Actress and Frank McGuinness’s The Hen House (1989) for BBC Television. She stars in the title role of George du Maurier‘s Trilby (1976), in an adaptation for the BBC’s Play of the Month, with Alan Badel as Svengali. She also stars in the BBC mini-series North & South (2004, from the novel by Elizabeth Gaskell) as Mrs. Thornton. She stars in the BBC sitcom Home Again (2006) and appears in the TV series Camelot (2011), which runs for one season. She has featured roles in the mini-series The Deep (2014) and the series Marcella (2016), an eight-episode murder mystery.

Along with other actresses, including Paola Dionisotti, Fiona Shaw, Juliet Stevenson and Harriet Walter, Cusack contributes to a book by Carol Rutter called Clamorous Voices: Shakespeare’s Women Today (1994). The book analyses modern acting interpretations of female Shakespearean roles.

Cusack marries British actor Jeremy Irons in 1978, and they have two sons, Samuel James and Maximilian Paul. Prior to marrying Irons, she gives birth to a son in 1967 and places the boy for adoption. In 2007, a journalist for the Irish Sunday Independent, Daniel McConnell, reveals that Cusack is the mother of left-wing general election candidate and now member of Irish parliament Richard Boyd Barrett. The two have since been reunited.

Cusack is a patron of the Burma Campaign UK, the London-based group campaigning for human rights and democracy in Burma. In 1998, she is named, along with her husband, in a list of the biggest private financial donors to the British Labour Party. In August 2010, she signs the “Irish artists’ pledge to boycott Israel” initiated by the Palestine Solidarity Campaign.

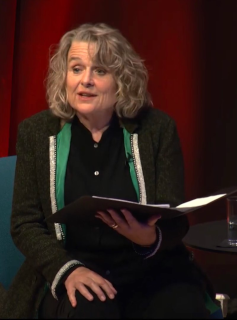

(Pictured: Sinéad Cusack reciting poetry for the British Library in October 2021)