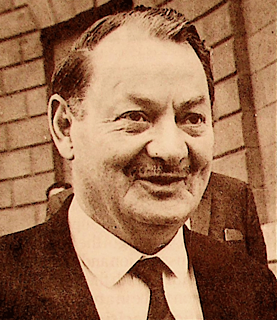

Prime Minister of Northern Ireland Terence O’Neill calls on the Taoiseach Jack Lynch at Iveagh House in Dublin on January 8, 1968. There is no advance publicity, largely to ensure that Ian Paisley is not able to upstage the meeting with his antics. The dozen reporters present are impressed at the friendly informality.

”How are you, Jack?” O’Neill says as he gets out of the car, extending his hand to the Taoiseach.

O’Neill is accompanied by his wife, Jean, and a number of officials. They have lunch in Iveagh House with the Taoiseach and his wife, Maureen, together with a number of official staff, and five of Lynch’s cabinet colleagues and their wives. The ministers are Tánaiste Frank Aiken, Minister for Finance Charles Haughey, Minister for Industry and Commerce George Colley, Minister for Agriculture and Fisheries Neil Blaney, and Minister for Transport and Power Erskine Childers.

The official statement at the end of the four-hour meeting states that progress has been made in “areas of consultation and co-operation.” The Taoiseach says they discussed industry, tourism, electricity supply, and trade, as well as tariff concessions, and “measures taken by both governments to prevent the spread of foot-and-mouth disease from Britain.”

Afterward, O’Neill returns to Northern Ireland by a different route in order to avoid any possible demonstration. Paisley has been developing a high profile for himself with his attacks on O’Neill in recent months. But he misses the opportunity to protest on this occasion. The next day he issues a statement regretting O’Neill’s return home. “I would advise Mr. Lynch to keep him,” Paisley announces.

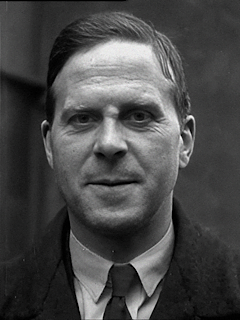

Five years earlier, in 1963, O’Neill becomes Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. From very early on, he tries to break down sectarian barriers between the two Northern communities. He also seeks to improve relations with the Republic of Ireland by eradicating the impasse in relations that has existed since the 1920s. He invites then-Taoiseach Seán Lemass to meet him at Stormont on January 14, 1965. Lemass courageously accepts the invitation. At their initial meeting, when they are briefly alone, Lemass says to O’Neill, ”I shall get into terrible trouble for this!” The Northern premier replies, ”No, Mr. Lemass, it is I who will get into terrible trouble.”

O’Neill makes his return visit to Dublin on February 9, 1965, and the two leaders agree to co-operate on tourism and electricity. It is Lemass who makes the most significant concessions, because the Constitution of Ireland does not recognise the existence of the North. Article 2 of the Constitution actually claims sovereignty over the whole island. Thus, by formally meeting the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, O’Neill claims that Lemass accorded him “a de facto recognition.”

The Taoiseach then bolsters this at their follow-up meeting in Iveagh House, Dublin, three weeks later. ”The place card in front of me at Iveagh House bore the inscription, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland,” O’Neill proudly explains. Surely this is tantamount to formal recognition. But many Unionists still have grave reservations about dealing with the Republic of Ireland.

In 1966, Ian Paisley establishes the Protestant Unionist Party (PUP) to oppose O’Neill. He rouses sectarian tension by holding mass demonstrations at which he brands O’Neill as the “Ally of Popery.” Nevertheless, public opinion polls indicate support for O’Neill’s leadership from both communities in the North.

After Jack Lynch replaced Lemass as Taoiseach in late 1966, O’Neill continues with his efforts to improve relations with the Dublin government by inviting Lynch to Stormont Castle. The Taoiseach travels to Belfast by car on December 11, 1967. There is no formal announcement of his visit, but word is leaked to Paisley after the Taoiseach’s car crosses the border.

Paisley arrives at Stormont with his wife and a handful of supporters, just minutes before the Taoiseach. With snow on the ground, two of Paisley’s church ministers, Rev. Ivan Foster and Rev. William McCrea, begin throwing snowballs at Lynch’s car. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) promptly grabs the two ministers. While they are being bundled into a police car, Paisley is bellowing, “No Pope here!” Lynch asks his traveling companion, T. K. Whitaker, “Which one of us does he think is the Pope?”

Paisley demands to be arrested by the RUC, and actually tries to get into the police car with his two colleagues, but he is pulled away. The two clergymen are taken to an RUC station and quickly released. Lynch ridicules the protest. “It was a seasonal touch,” he says. “It reminds me of what happens when I go through a village at home and the boys come and throw snowballs.”

Paisley says he had come to protest against “the smuggling” of Lynch into Stormont. If he had known about the visit earlier, he says that he would have brought along 10,000 people to protest. Denouncing O’Neill, as a “snake in the grass,” he goes on to accuse Lynch of being “a murderer of our kith and kin.” In an editorial, the Unionist Newsletter proclaims that ”there is no doubt that Capt. O’Neill has the full support of his colleagues and of the country.”

O’Neill’s four formal meetings with Lynch and his predecessor contribute to a thaw in relations at the summit between Belfast and Dublin, but the whole process is exploited by others to fan the flames of Northern sectarianism.

People do not realise it in early 1968, but Northern Ireland is about to explode. On October 5, 1968, people gather in Derry for a civil rights march that has been banned by Stormont. When the march begins, it is viciously attacked by the RUC. This ignites a series of further protests, which ultimately leads to Bloody Sunday, and the eruption of the Troubles for the next quarter of a century.

(From: “Meetings helped thaw relations before the North exploded,” Irish Examiner, http://www.irishexaminer.com, January 8, 2018)