The murder of Robert McCartney occurs in Belfast, Northern Ireland, on the night of January 30, 2005, and is carried out by members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army.

McCartney, born in 1971, is a Roman Catholic and lives in the predominantly nationalist Short Strand area of east Belfast, and is said by his family to be a supporter of Sinn Féin. He is the father of two children and is engaged to be married in June 2005 to his longtime girlfriend, Bridgeen Hagans.

McCartney is involved in an altercation in Magennis’ Bar on May Street in Belfast’s city centre on the night of January 30, 2005. He is found unconscious with stab wounds on Cromac Street by a police patrol car and dies at the hospital the following morning. He is 33 years old.

The fight arises when McCartney is accused of making an insulting gesture or comment to the wife of an IRA member in the social club. When his friend, Brendan Devine, refuses to accept this or apologise, a brawl begins. McCartney, who is attempting to defend Devine, is attacked with a broken bottle and then dragged into Verner Street, beaten with metal bars and stabbed. Devine also suffers a knife attack, but survives. The throats of both men are cut and McCartney’s wounds include the loss of an eye and a large blade wound running from his chest to his stomach. Devine is hospitalised under armed protection.

When Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) officers arrive at the scene, their efforts to investigate the pub and surrounding area are met with an impromptu riot. Rioting by youths, specifically attacking the police, force them to pull back from the area, which delays initial investigation. Police with riot gear arrive later in the evening and are also attacked. Alex Maskey of Sinn Féin claims, “It appears the PSNI is using last night’s tragic stabbing incident as an excuse to disrupt life within this community, and the scale and approach of their operation is completely unacceptable and unjustifiable.” There are suggestions that the rioting is organised by those involved in the murder, so that a cleanup operation can take place in and around where the murder took place. Clothes worn by McCartney’s attackers are burned, CCTV tapes are removed from the bar and destroyed and bar staff are threatened. No ambulance is called. McCartney and Devine are noticed by a police car on routine patrol, who call an ambulance to the scene.

When the police launch the murder investigation they are met with a “wall of silence” None of the estimated seventy or so witnesses to the altercation come forward with information. In conversations with family members, seventy-one potential witnesses claim to have been in the pub’s toilets at the time of the attacks. As the toilet measures just four feet by three feet, this leads to the toilets being dubbed the TARDIS, after the time machine in the television series Doctor Who, which is much bigger on the inside than on the outside.

Sinn Féin suspends twelve members of the party and the IRA expels three members some weeks later.

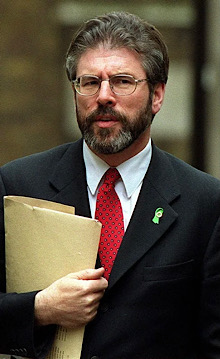

Gerry Adams, then president of Sinn Féin, urges witnesses to come forward to “the family, a solicitor, or any other authoritative or reputable person or body”. He continues, “I want to make it absolutely clear that no one involved acted as a republican or on behalf of republicans.” He suspends twelve members of Sinn Féin. He stops short of asking witnesses to contact the police directly. The usefulness of making witness statements to the victim’s family or to a solicitor is derided by the McCartneys and by a prominent lawyer and Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) politician, Alban Maginness, soon afterward.

On February 16, 2005, the IRA issues a statement denying involvement in the murder and calls on the perpetrators to “take responsibility.”

On March 8, 2005, the IRA issues an unprecedented statement saying that four people are directly involved in the murder, that the IRA knows their identity, that two are IRA volunteers, and that the IRA has made an offer to McCartney’s family to shoot the people directly involved in the murder.

In May 2005, Sinn Féin loses its council seat in the Pottinger area, which covers the Short Strand, with the McCartney family attributing the loss to events surrounding the murder.

Since this time, the sisters of McCartney have maintained an increasingly public campaign for justice, which sees Sinn Féin chief negotiator Martin McGuinness make a public statement that the sisters should be careful that they are not being manipulated for political ends.

The McCartney family travels to the United States during the 2005 Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations where they are met by U.S. Senators (including Hillary Clinton and John McCain) and U.S. President George W. Bush who express support in their campaign for justice.

Support for Sinn Féin by some American politicians is diminished. Adams is not invited to the White House in 2005 and Senator Edward Kennedy backs out of a meeting that had been previously scheduled. The McCartney family, previously Sinn Féin supporters, pledge to never support the party again, and a cousin of the sisters who raised funds for Sinn Féin in the United States insist that she will not be doing so in the future.

On May 5, 2005, Terence Davison and James McCormick are remanded in custody, charged with murdering McCartney and attempting to murder Devine respectively. McCormick is originally from England. They are held in the republican wing of HM Prison Maghaberry. Roughly four months later the accused are released on bail, and in June 2006, the attempted murder charge against McCormick is dropped, leaving a charge of causing an affray. On June 27, 2008, Terence Davison is found not guilty of committing the murder. Two other men charged with affray are also cleared.

In November 2005, the McCartney sisters and Bridgeen Hagans, the former partner of McCartney, refuse to accept the Outstanding Achievement award at the Women of the Year Lunch, because it would mean their sharing a platform with Margaret Thatcher, whom they dislike.

In December 2005, the McCartney sisters meet with UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, and tell him they believe the murder had been ordered by a senior IRA member, and that Sinn Féin was still not doing all it could to help them.

On January 31, 2007, two years after the murder, and in line with the party’s new policy of supporting civil policing, Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams says that anyone with information about the murder should go to the police.

On May 5, 2015, an IRA man believed to have been involved in the death of McCartney, Gerard ‘Jock’ Davison, is shot dead. Early in the investigation the police rule out either a sectarian attack or the involvement of dissident republicans.

The McCartney family has lived in the Short Strand area of Belfast for five generations. However, some local people in the Short Strand area, which is a largely nationalist area, does not welcome their dispute with the IRA. A campaign of intimidation by republicans drives members of the family and McCartney’s former fiancée to relocate and also causes one member to close her business in the city centre. The last McCartney sister to leave the area, Paula, departs Short Strand on October 26, 2005.

The family remain in contact with the family of Joseph Rafferty of Dublin, who dies under similar circumstances on April 12, 2005.