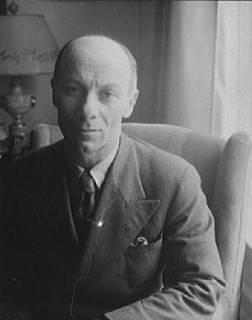

Hugh Edward Kennedy, Fine Gael politician, barrister and judge, is born in Abbotstown, Dublin on July 11, 1879. He serves as Attorney General of Ireland from 1922 to 1924, a Judge of the Supreme Court of Ireland from 1924 to 1936 and Chief Justice of Ireland from 1924 to 1936. He serves as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Dublin South constituency from 1923 to 1927. As a member of the Irish Free State Constitution Commission, he is also one of the constitutional architects of the Irish Free State.

Kennedy is the son of the prominent surgeon Hugh Boyle Kennedy. His younger sister is the journalist Mary Olivia Kennedy. He studies for the examinations of the Royal University of Ireland while a student at University College Dublin and King’s Inns, Dublin. He is called to the Bar in 1902. He is appointed King’s Counsel in 1920 and becomes a Bencher of King’s Inn in 1922.

During 1920 and 1921, Kennedy is a senior legal adviser to the representatives of Dáil Éireann during the negotiations for the Anglo-Irish Treaty. He is highly regarded as a lawyer by Michael Collins, who later regrets that Kennedy had not been part of the delegation sent to London in 1921 to negotiate the terms of the treaty.

On January 31, 1922, Kennedy becomes the first Attorney General in the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State. Later that year he is appointed by the Provisional Government to the Irish Free State Constitution Commission to draft the Constitution of the Irish Free State, which is established on December 6, 1922. The functions of the Provisional Government are transferred to the Executive Council of the Irish Free State. He is appointed Attorney General of the Irish Free State on December 7, 1922.

In 1923, Kennedy is appointed to the Judiciary Commission by the Government of the Irish Free State, on a reference from the Government to establish a new system for the administration of justice in accordance with the Constitution of the Irish Free State. The Judiciary Commission is chaired by James Campbell, 1st Baron Glenavy, who had also been the last Lord Chancellor of Ireland. It drafts the Courts of Justice Act 1924 for a new court system, including a High Court and a Supreme Court, and provides for the abolition, inter alia, of the Court of Appeal in Ireland and the Irish High Court of Justice. Most of the judges are not reappointed to the new courts. Kennedy personally oversees the selection of the new judges and makes impressive efforts to select them on merit alone. The results are not always happy. His diary reveals the increasingly unhappy atmosphere, in the Supreme Court itself, due to frequent clashes between Kennedy and his colleague Gerald Fitzgibbon, since the two men prove to be so different in temperament and political outlook that they find it almost impossible to work together harmoniously. In a similar vein, Kennedy’s legal opinion and choice of words could raise eyebrows amongst legal colleagues and fury in the Executive Council e.g. regarding the Kenmare incident.

Kennedy is also a delegate of the Irish Free State to the Fourth Assembly of the League of Nations between September 3-29, 1923.

Kennedy is elected to Dáil Éireann on October 27, 1923, as a Cumann na nGaedheal TD at a by-election in the Dublin South constituency. He is the first person to be elected in a by-election to Dáil Éireann. He resigns his seat when he is appointed Chief Justice of Ireland in 1924.

On June 5, 1924, Kennedy is appointed Chief Justice of Ireland, thereby becoming the first Chief Justice of the Irish Free State. He is also the youngest person appointed Chief Justice of Ireland. When he is appointed, he is 44 years old. Although the High Court of Justice and the Court of Appeal had been abolished and replaced by the High Court and the Supreme Court respectively, one of his first acts is to issue a practice note that the wearing of wigs and robes will continue in the new courts. This practice is still continued in trials and appeals in the High Court and the Supreme Court (except in certain matters). He holds the position of Chief Justice until his death on December 1, 1936, in Goatstown, Dublin.

In September 2015, a biography by Senator Patrick Kennedy (no relation) is written about Kennedy called Hugh Kennedy: The Great but Neglected Chief Justice.