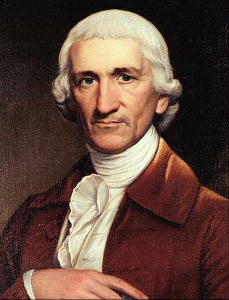

Francis Rawdon Chesney, British general and explorer, is born in Annalong, County Down, on March 16, 1789.

Chesney is a son of Captain Alexander Chesney, an Irishman of Scottish descent who, having emigrated to South Carolina in 1772, serves under Lord Francis Rawdon-Hastings (afterwards Marquess of Hastings) in the American War of Independence, and subsequently receives an appointment as coast officer at Annalong, County Down, where Chesney is born.

Lord Rawdon gives Chesney a cadetship at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, and he is gazetted to the Royal Artillery in 1805. Although he rises to be lieutenant-general and colonel-commandant of the 14th brigade Royal Artillery (1864), and general in 1868, Chesney’s memory lives not for his military record, but for his connection with the Suez Canal, and with the exploration of the Euphrates valley, which starts with his being sent out to Constantinople in the course of his military duties in 1829, and his making a tour of inspection in Egypt and Syria. In 1830, after taking command of 7th Company, 4th Battalion Royal Artillery in Malta, he submits a report on the feasibility of making a Suez Canal. This is the original basis of Ferdinand de Lesseps’ great undertaking. In 1831 he introduces to the home government the idea of opening a new overland route to India, by a daring and adventurous journey along the Euphrates valley from Anahto the Persian Gulf. Returning home, Acting Lt. Colonel Chesney busies himself to get support for the latter project, to which the East India Company’s board is favourable. In 1835 he is sent out in command of a small expedition, on which he takes a number of soldiers from 7th Company RA and for which Parliament votes £20,000, in order to test the navigability of the Euphrates.

After encountering immense difficulties, from the opposition of the Egyptian pasha, and from the need of transporting two steamers, one of which is subsequently lost, in sections from the Mediterranean Sea over the hilly country to the river, they successfully arrive by water at Bushirein the summer of 1836, and prove Chesney’s view to be a practical one. In the middle of 1837, Chesney returns to England, and is given the Royal Geographical Society’s gold medal, having meanwhile been to India to consult the authorities there. The preparation of his two volumes on the expedition, published in 1850, is interrupted by his being ordered out in 1843 to command the artillery at Hong Kong.

In 1847, his period of service is completed, and he goes home to Ireland, to a life of retirement. However, in 1856 and again in 1862 he goes out to the East to take a part in further surveys and negotiations for the Euphrates valley railway scheme, which, however, the government does not take up, in spite of a favourable report from the House of Commons committee in 1871. In 1868 Chesney publishes a further volume of narrative on his Euphrates expedition.

In 1869, Lesseps greets him in Paris as the “father “ of the canal. Francis Rawdon Chesney dies at the age of 82 in Mourne, County Down, on January 30, 1872.