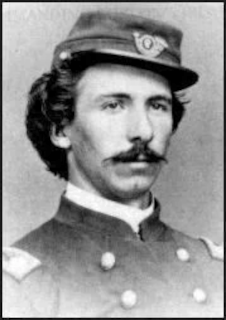

Patrick Robert Guiney, American Civil War soldier, is born in Parkstown, County Tipperary, on January 15, 1835.

Guiney is the second and eldest surviving son of James Roger Guiney, who is descended from Jacobites, and Judith Macrae. His father, impoverished after a failed runaway marriage, brings with him on his second voyage to New Brunswick his favourite child Patrick, not yet six years old. After some years, his mother and younger brother, William, rejoin her husband, recently crippled by a fall from his horse. They settle in Portland, Maine. The young Guiney works as a wheel boy in a rope factory, and at the age of fourteen apprenticed to a machinist in Lawrence, Massachusetts, but stays only a year and a half before returning to Portland.

Guiney hopes to better himself through education and attends the public grammar school. He matriculates at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. His depleting finances cause him to leave after about a year, despite the fact that the college president offers to make some arrangement for him to stay, which his honor would not allow him to accept. His book-loving father having meanwhile died, he goes to study for the Bar under Judge Walton, and is admitted in Lewiston, Maine, in 1856, taking up the practice of criminal law.

In politics he is a Republican. For the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, he wins its first suit. In 1859 he marries in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, Boston, Janet Margaret Doyle, related to James Warren Doyle, Bishop of Kildare and Leighlin. They have one son, who dies in infancy, and one daughter, the poet and essayist Louise Imogen Guiney. Home life in Roxbury and professional success are cut short by the outbreak of the American Civil War.

Familiar with the manual of arms, Guiney enlists for example’s sake as a private, refusing a commission from Governor John A. Andrew until he has worked hard to help recruit the 9th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. By June 1861, he is a captain. In July 1862, the first colonel having died from a wound received in action, Lieutenant Colonel Guiney succeeds him to the command. He wins high official praise, notably for courage and presence of mind at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill in Hanover County, Virginia. Here, after three successive color-bearers had been shot down, he himself reportedly seizes the flag, throws aside coat and sword-belt, rises white-shirted and conspicuous in the stirrups, inspires a final rally, and turns the fortune of the day.

Guiney fights in over thirty engagements, including the Battle of Antietam, the Battle of Fredericksburg, and the Battle of Chancellorsville.

The 9th Massachusetts is present at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in second brigade first division V Corps on July 1, 1863. Col Jacob B. Sweitzer the brigade commander, detaches Guiney’s regiment for picket duty. Consequently, the regiment misses the second day’s fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg.

In 1864, through the Battle of the Wilderness, Guiney frequently has been in command of his brigade, the second brigade, first division, V Corps. After many escapes from dangerous combats without serious injury, he is shot in the face by a sharpshooter at the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5, 1864. The Minié ball destroys his left eye, and inflicts, it is believed, a fatal wound. During an interval of consciousness, however, he insists on an operation which saves his life. He is honorably discharged and mustered out of the U.S. Volunteers on June 21, 1864, just before the mustering out of his old regiment.

On February 21, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominates Guiney for the award of the honorary grade of brevet brigadier general, to rank from March 13, 1865, for gallant and meritorious services during the war. The U.S. Senate confirms the award on April 10, 1866.

Kept alive for years by nursing, Guiney runs unsuccessfully for the United States Congress on a sort of “Christian Socialist” platform, is elected assistant district attorney (1866–70), and acts as consulting lawyer (no longer being able to plead) on many locally celebrated cases.

Guiney’s last exertions are devoted to the defeat of the corruption and misuse of the Probate Court of Suffolk County, Massachusetts, of which he had become registrar (1869–77). He dies suddenly on March 21, 1877, in Boston and is found kneeling against an elm in the little park near his home. General Guiney is Commandant of the Loyal Legion, Major-General Commandant of the Veteran Military League, member of the Charitable Irish Society of Boston, and one of the founders and first members of the Catholic Union of Boston. He also publishes some literary criticism, a few graphic prose sketches and some verse.