Gordon Elliott, a County Meath-based National Hunt racehorse trainer, is born on March 2, 1978. After riding as an amateur jockey, he takes out a trainer’s licence in 2006. He is 29 when his first Grand National entry, the 33 to 1 outsider Silver Birch, wins the 2007 race. In 2018 and 2019 he wins the Grand National with Tiger Roll, ridden by Davy Russell and owned by Gigginstown House Stud, the first horse since Red Rum to win the race twice. In 2018 he also wins the Irish Grand National, with General Principle. On two occasions, in 2017 and 2018, he is the top trainer at the Cheltenham Festival.

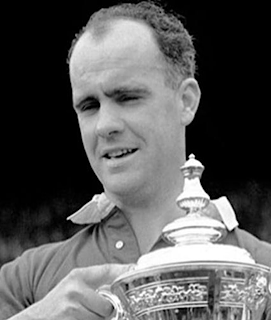

With little family background in racing, Elliott is sometimes described as Irish racing’s great “blow-in.” The son of a panel beater, he grows up in Summerhill, County Meath, and enters the racing world at the age of thirteen, working for trainer Tony Martin on weekends and holidays. He takes out a licence as an amateur jockey when he is sixteen and rides on the racecourse and in point-to-points. His first winner on the racecourse comes on Caitriona’s Choice in a bumper at Ballinrobe Racecourse. He goes on to ride a total of 200 point-to-point winners and 46 winners on the racecourse, with the highlight of his riding career being his win in the Champion INH Flat Race on the Nigel Twiston-Davies-trained King’s Road in 1998. He also has five winners in the United States. Although based mainly with Tony Martin during his riding career, he spends a year in England with trainer Martin Pipe. He retires as a jockey through injury in 2005.

Elliott takes out his trainer’s licence in 2006 and has his first winner at Perth Racecourse on June 11, 2006. On April 14, 2007, he becomes the youngest trainer ever to win the Grand National. The winner, Silver Birch, is owned by Brian Walsh of County Kildare, and ridden by Robbie Power. Despite having won the Grand National, Elliott has not at this stage trained a winner on the track back home in Ireland. The first winner he trains in Ireland is Toran Road at Kilbeggan Racecourse on May 5, 2007.

Although best known for his victories over jumps, Elliott has a major win on the flat in August 2010 when Dirar wins the Ebor Handicap at York Racecourse. He also has victories at Royal Ascot, with Commissioned winning the Queen Alexandra Stakes in 2016 and Pallasator winning the same race in 2018.

Originally based at Capranny Stables, a rented yard in Trim, County Meath, Elliott purchases the 78-acre Cullentra House Farm at Longwood, County Meath in 2011 and builds a training facility with stabling for over 200 horses, gallops, schooling grounds, and an equine pool.

Elliott’s first winner at the Cheltenham Festival as a trainer is Chicago Grey in the National Hunt Chase Challenge Cup in 2011. He wins the 2016 Cheltenham Gold Cup with Don Cossack. In 2017 he is top trainer at the Cheltenham Festival and the following year repeats the achievement.

On April 2, 2018, Elliott wins the Irish Grand National with General Principle, ridden by JJ Slevin. He has saddled 13 of the 30 horses in the field. That year he also wins the Aintree Grand National with his horse Tiger Roll, ridden by Davy Russell and owned by Michael O’Leary’s Gigginstown House Stud, narrowly beating the Willie Mullins runner Pleasant Company. He also trains the third place horse Bless The Wings. He wins the Aintree Grand National again in 2019 with Tiger Roll, only the sixth repeat winner in the race’s history.

On February 28, 2021, the Irish Horseracing Regulatory Board (IHRB) launches an investigation into an image of Elliott, which is widely circulated on social media, sitting on a dead horse and making a peace sign. Elliott confirms the photograph is genuine, issues an apology and says he is fully cooperating with the investigation. The animal rights organisation People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and the British Horseracing Authority condemn the photograph. On March 1, the British Horseracing Authority announces that Elliott will be banned from racing horses in Britain while the investigation in Ireland takes place, although the horses will be allowed to run if transferred to another trainer. It is confirmed that the photo was taken in 2019 and shows a horse owned by Gigginstown House Stud, Morgan, that had died while being ridden on the gallops.

Minister of State for Sport Jack Chambers says that Elliott must be “held fully accountable for his actions” and that the photograph shows “a complete and profound error of judgement.” He tells Morning Ireland that he is “shocked, appalled and horrified” by the image and that it is “really disturbing from an animal welfare perspective.”

On March 2, Cheveley Park Stud announces that they will move their horses Envoi Allen and Quilixios to Henry de Bromhead and Sir Gerhard to Willie Mullins. Elliott’s leading owners, Michael and Eddie O’Leary, through their Gigginstown House Stud, express their support for him despite being “deeply disappointed by the unacceptable photo.”

On March 5, 2021, the IHRB convenes a hearing and bans Elliott from racing for twelve months with six months suspended, leaving him unable to train or attend a race meeting or point-to-point until September. He is also ordered to pay costs of €15,000. He accepts the ruling. Later that month the stable employee who took the photograph is banned for nine months (with seven suspended).

In July 2021, Elliott is featured in a BBC Panorama programme that investigates the fate of British and Irish racehorses who end up in abattoirs. Three of the horses were formerly trained by Elliott, who denies having sent them to the abattoir. He says two of the horses were sent to a horse dealer to be re-homed or humanely euthanised, while the third was given to someone else at the owner’s request. The former horses were bay mare Kiss me Kayf, who had had no success on the racecourse, and bay gelding High Expectations, who had won seven races. The latter horse, owned by Simon Munir and Isaac Souede, was grey gelding Vyta Du Roc, who won the 2016 Reynoldstown Novices’ Chase. Following the programme, Munir and Souede remove their horses from Elliott’s yard.

In 2007, Elliott wins the inaugural Meath Sportsperson of the Year award. He wins the award again in 2018 and 2019.

Elliott is engaged to champion point-to-point rider Annie Bowles, with whom he sets up Cullentra House Stables. The couple separates and Bowles marries Ballarat trainer Archie Alexander.[28]