The American Civil War begins on April 12, 1861. There is perhaps no other ethnic group so closely identified with the Civil War years and the immediate aftermath of the war as Irish Americans.

Of those Irish who come over much later than the founding generations, fully 150,000 of them join the Union army. Unfortunately, statistics for the Confederacy are sketchy at best. Still, one has but to listen to the Southern accent and listen to the sorts of tunes Southern soldiers love to sing to realize that a great deal of the South is settled by Irish immigrants. But because the white population of the Confederate states is more native-born than immigrant during the Civil War years, there does not seem as much of a drive in the Southern army to recognize heritage in the names and uniforms of regiments as there is in the Union forces.

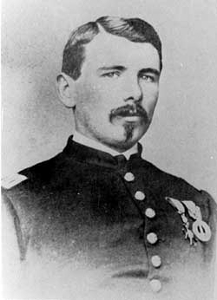

In the Union army there is the fabled Irish Brigade, likely the best known of any brigade organization, organized in 1861 and led by the flamboyant General Thomas Francis Meagher. They go into battle with an emerald green flag with a large golden harp in its center, celebrating their heritage even in the midst of death. The Irish Brigade makes an unusual reputation for dash and gallantry. It belongs to the First Division of the Second Corps and is numbered as the Second Brigade. The Irish Brigade loses over 4,000 men in killed and wounded during the war; more men than ever belong to the brigade at any given time. The Irish Brigade is commanded, in turn, by General Thomas Francis Meagher, Colonel Patrick Kelly (killed), General Thomas A. Smyth (killed), Colonel Richard Byrnes (killed), and General Robert Nugent.

In the North, centers of Irish settlement are Boston and New York, both of which have sizeable Irish neighborhoods. There are major immigration periods in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s. The numbers steadily increase until, according to the 1860 census, well over one and a half million Americans claimed to have been born in Ireland. The majority of these live in the North. There are periods of severe economic difficulties both before and after the war when the immigrant Irish are singled out for the distrust and hatred of their fellow Americans. “No Irish Need Apply” is a frequently seen placard sign above the doors of factories, shops, warehouses, and farms.

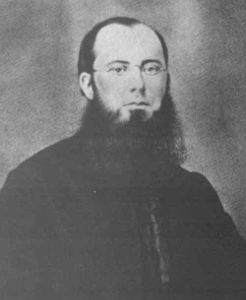

The Irish are chiefly distrusted because they are Catholic, and there is much opposition in the United States to the Church of Rome. The frustration this prejudice causes leads indirectly to the boil-over of tempers in July 1863, when the first official draft is held. A mob of mostly immigrant laborers gather at the site of the draft lottery, and as names are called and those not wealthy enough to purchase a substitute are required to join up, the mob’s temper flares.

The situation escalates into full-scale rioting. For three days, cities like New York and Boston are caught up in a rampage of looting, burning, and destruction. Many of the rioters are frustrated Irish laborers who cannot get jobs, and their targets are draft officials, as well as free blacks living in the North, who seem able to get jobs that the Irish are denied. It takes the return of armed troops from the fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg to bring the cities back to peace and quiet.

Such events do little to help the image of the Irish in America, until many years after the war. Despite their wartime heroics, many Irish veterans come home to find the same ugly bias they faced before going off to fight for the Union. Many of them choose to go into the post war army.

Still others follow Thomas Meagher into Canada, where they join up in an attempt to free Canada from British domination. Many simply choose to remain in the Eastern cities, hoping matters will improve as time goes by. Eventually things do get better for the Irish, but it is many long years before ugly anti-Irish prejudice fades.