Ernest Bernard (Ernie) O’Malley, Irish republican revolutionary and writer, is born on May 26, 1897, in Ellison Street, Castlebar, County Mayo, the second child among nine sons and two daughters of Luke Malley, solicitor’s clerk, of County Mayo, and Marion Malley (née Kearney) of County Roscommon. Christened Ernest Bernard Malley, his adoption of variations on this name reflects his enthusiasm for a distinctively Irish identity – an enthusiasm that lay at the heart of his republican career and outlook.

In 1906, O’Malley’s family moves to Dublin, where he attends the Christian Brothers‘ School, North Richmond Street. In 1915, he begins to study medicine at University College Dublin (UCD). Having initially intended to follow his older brother into the British Army, he rather joins the Irish Volunteers in the wake of the 1916 Easter Rising, as a member of F Company, 1st Battalion, Dublin Brigade. He becomes a leading figure in the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Irish War of Independence which the Easter Rising helps to occasion. In 1918, having twice failed his second-year university examination, he leaves home to commit himself to the republican cause. He is initially a Volunteer organiser with the rank of second lieutenant, under the instruction of Richard Mulcahy, operating in Counties Tyrone, Offaly, Roscommon, and Donegal. His work in 1918 involves the reorganisation, or new establishment, of Volunteer groups in the localities.

In August 1918, O’Malley is sent to London by Michael Collins to buy arms. During 1919 he works as an IRA staff captain attached to General Headquarters (GHQ) in Dublin, and also trains and organises Volunteers in Counties Clare, Tipperary, and Dublin. He has a notable military record with the IRA during the Irish War of Independence and is a leading figure in attacks on Hollyford barracks in County Tipperary (May 1920), Drangan barracks in County Kilkenny (June 1920), and Rearcross barracks in County Tipperary (July 1920). His IRA days thus involve him with comrades such as Dan Breen, Séumas Robinson, and Seán Treacy. In December 1920, he is captured in County Kilkenny by Crown forces. He escapes from Dublin’s Kilmainham Gaol in February 1921, to take command of the IRA’s 2nd Southern Division, holding the rank of commandant-general.

O’Malley’s republican commitment has political roots in his conviction that Ireland should properly be fully independent of Britain, and that violence is a necessary means to achieve this end. But the causes underlying his revolutionism are layered. Family expectations of respectable, professional employment combined with a religious background and an enthusiasm for soldiering provide some of the foundations for his IRA career. As an IRA officer he enjoys professional, military expression for a visceral Catholic Irish nationalism. He also finds excitement, liberation from the frequent dullness of his life at home, defiant rebellion against his non-republican parents, an alternative to his stalled undergraduate career, and, in political and cultural Irish separatism, a decisive resolution of the profound tension between his anglocentrism and his anglophobia.

O’Malley rejects the 1921 Anglo–Irish Treaty as an unacceptable compromise. He spends the 1921 truce period training IRA officers in his divisional area, in preparation for a possible renewal of fighting. He is, in the event, to be a leading anti-treatyite in the 1922–23 Irish Civil War. In the Four Courts in 1922, at the start of the latter conflict, he is captured on the republicans’ capitulation on June 30 but then manages to escape from captivity. Subsequently he is appointed assistant Chief of Staff of the anti-Treaty IRA and also becomes part of a five-man anti-Treaty army council, along with Liam Lynch, Liam Deasy, Frank Aiken and Thomas Derrig.

O’Malley is dramatically captured and badly wounded by Free State forces in Dublin in November 1922. Imprisoned until July 1924, he is during the period of his incarceration elected as a TD for Dublin North in the 1923 Irish general election and is also a forty-one-day participant in the republican hunger strike later that year. Following release from prison, he returns home to live with his parents in Dublin. He decides not to focus his post-revolutionary energy on a political career. During 1926–28 and 1935–37 he unsuccessfully tries to complete his medical degree at UCD, but increasingly his post-1924 efforts are directed toward life as a Bohemian traveler and writer. He spends much of 1924–26 on a recuperative journey through France, Spain, and Italy; and 1928–35 traveling widely in North America. During 1929–32 he spends time in New Mexico and Mexico City. In Taos, New Mexico, he mixes with, and is influenced by, writers and artists as he works on what are to become classic autobiographies of the Irish revolution: On Another Man’s Wound (1936) and The Singing Flame (1978).

O’Malley meets Helen Hooker, daughter of Elon and Blanche Hooker, in Connecticut in 1933. They marry in London in 1935, each rejecting something of their prior lives in the process: he, his Irish republicanism, through marriage to somebody entirely unconnected with that world; she, her wealthy and respectable upbringing, through liaison with a Catholic, Irish, unemployed, bohemian ex-revolutionary. They settle first in Dublin then, from 1938 onward, primarily in County Mayo. Burrishoole Lodge, near Newport, is his main base until 1954, when he moves to Dublin. Three children are born to the O’Malleys: Cahal (1936), Etáin (1940), and Cormac (1942). Sharing enthusiasm for the arts, he and Helen enjoy several years of intimacy. However, by the mid-1940s their relationship has frayed. In 1950, Helen kidnaps (the word is used by both parents and by all three children) the couple’s elder two children and takes them to the United States. From there she divorces O’Malley in 1952. Cormac remains with his father.

O’Malley’s post-American years are devoted to a number of projects. He writes extensively, including work for The Bell and Horizon. He is involved with the film director John Ford in the making of his Irish films, including The Quiet Man (1952). He gives radio broadcasts on Mexican painting for BBC Third Programme (1947), and on his IRA adventures for Radio Éireann (1953). In the latter year he suffers a heart attack, and his remaining years are scarred by ill health. He dies of heart failure on March 25, 1957, in Howth, County Dublin, at the house of his sister Kathleen. Two days later he is given a state funeral with full military honours. He is buried in the Malley family plot in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin.

O’Malley exemplifies some important themes in modern Irish political and intellectual history. His powerful memoirs form part of a tradition of writing absorbedly about Ireland, while under idiosyncratic emigrant influences which lend the writing much of its distinctiveness. His aggressive republicanism exemplifies a persistent but ultimately unrealisable tradition of uncompromising IRA politics. His unflinching single-mindedness is the condition for much courageous and striking activity, but also lay behind his infliction and his suffering of much pain. Literary, intellectual, and defiantly dissident, he is the classic bohemian revolutionary. His historical significance lies in his having been both a leading Irish revolutionary and the author of compelling autobiographical accounts of those years. His memoirs are distinguished from their rivals on the shelf by subtlety, self-consciousness, and literary ambition. In particular, his preparedness to identify motives for Irish revolutionary action, beyond the terms of ostensible republican purpose, renders his writing of great value to historians. Similarly, the large body of archival material left in his name (especially, perhaps, the papers held in UCD archives, and those in the private possession of his children) leaves scholars in his debt. The most striking and evocative visual images of O’Malley are, arguably, the set of photographic portraits taken in 1929 by Edward Weston and held at the University of Arizona‘s Center for Creative Photography (CCP). These capture with precision his reflective concentration, his piercing earnestness, and his troubled intensity.

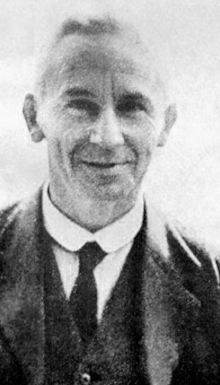

(From: “O’Malley, Ernest Bernard (‘Ernie’)” by Richard English, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009 | Pictured: Photograph of Ernie O’Malley taken by Helen Hooker, New York City, 1934)