Standish James O’Grady, author, journalist, and historian, dies on May 18, 1928, at Shanklin, Isle of Wight, Hampshire, England.

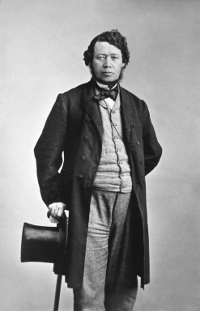

O’Grady is born on March 22, 1846, at Castletown, County Cork, the son of Reverend Thomas O’Grady, the scholarly Church of Ireland minister of Castletown Berehaven, County Cork, and Susanna Doe. After a rather severe education at Tipperary Grammar School, O’Grady follows his father to Trinity College, Dublin, where he wins several prize medals and distinguishes himself in several sports.

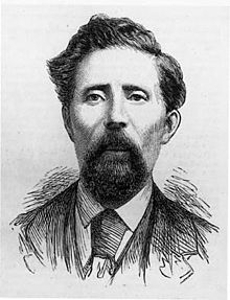

O’Grady proves too unconventional of mind to settle into a career in the church and earns much of his living by writing for the Irish newspapers. Reading Sylvester O’Halloran‘s General history of Ireland sparks an interest in early Irish history. After an initial lukewarm response to his writing on the legendary past in History of Ireland: Heroic Period (1878–81) and Early Bardic Literature of Ireland (1879), he realizes that the public wants romance, and so follows the example of James Macpherson in recasting Irish legends in literary form, producing historical novels including Finn and his Companions (1891), The Coming of Cuculain (1894), The Chain of Gold (1895), Ulrick the Ready (1896) and The Flight of the Eagle (1897), and The Departure of Dermot (1913).

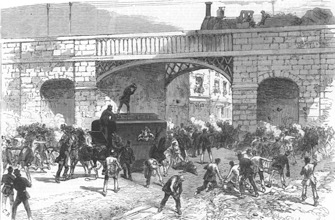

O’Grady also studies Irish history of the Elizabethan period, presenting in his edition of Sir Thomas Stafford‘s Pacata Hibernia (1896) the view that the Irish people have made the Tudors into kings of Ireland in order to overthrow their unpopular landlords, the Irish chieftains. His The Story of Ireland (1894) is not well received, as it sheds too positive a light on the rule of Oliver Cromwell for the taste of many Irish readers. He is also active in social and political campaigns in connection with such issues as unemployment and taxation.

Until 1898, he works as a journalist for the Daily Express of Dublin, but in that year, finding Dublin journalism in decline, he moves to Kilkenny to become editor of the Kilkenny Moderator. It is here he becomes involved with Ellen Cuffe, Countess of Desart and Captain Otway Cuffe. He engages in the revival of the local woolen and woodworking industries. In 1900 he founds the All-Ireland Review and returns to Dublin to manage it until it ceases publication in 1908. O’Grady contributes to James Larkin‘s The Irish Worker paper.

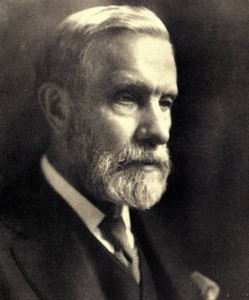

O’Grady’s works are an influence on William Butler Yeats and George Russell and this leads to him being known as the “Father of the Celtic Revival.” Being as much proud of his family’s Unionism and Protestantism as of his Gaelic Irish ancestry, identities that are increasingly seen as antithetical in the late 1800s, he is described by Augusta, Lady Gregory as a “fenian unionist.”

Advised to move away from Ireland for the sake of his health, O’Grady passes his later years living with his eldest son, a clergyman in England, and dies on the Isle of Wight on May 18, 1928.

O’Grady’s eldest son, Hugh Art O’Grady, is for a time editor of the Cork Free Press before he enlists in World War I early in 1915. He becomes better known as Dr. Hugh O’Grady, later Professor of the Transvaal University College, Pretoria, who writes the biography of his father in 1929.