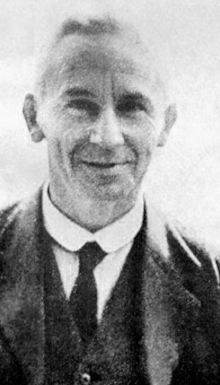

Seán O’Hegarty, a prominent member of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in County Cork during the Irish War of Independence, is born on March 21, 1881, in Cork, County Cork. He serves as O/C of the Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA after the deaths of Tomás Mac Curtain and Terence MacSwiney.

O’Hegarty comes from a family with strong nationalist roots. His parents are John, a plasterer and stucco worker, and Katherine (née Hallahan) Hegarty. His elder brother is Patrick Sarsfield O’Hegarty, the writer. His parents’ families emigrated to the United States after the Great Famine, and his parents married in Boston. His father is a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). In 1888, his father dies of tuberculosis at the age of 42, and his mother has to work to support the family.

O’Hegarty is educated at the Christian Brothers North Monastery school in Cork. By 1902, he has left school to work as a sorter in the local post office, rising to post office clerk. He is a supporter of the Gaelic revival, Irish traditional music, and Gaelic games. A committed sportsman, in his twenties he is captain of the Post Office HQ’s hurling team. He follows his brother Patrick into Conradh na Gaeilge and eventually the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Republican Brotherhood. He is a member of the Celtic Literary Society by 1905 and founds the Growney branch of Conradh na Gaeilge in 1907. A puritanical character by nature, he is a non-smoker and never drinks.

O’Hegarty is a founder of the local branch of the Irish Volunteers in Cork in December 1913. In June of the following year, he is appointed to the Cork section of the Volunteer Executive, and then to the Military Council. In October, the Dublin government discovers his illegal activities, and he is dismissed. Excluded from Cork under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) regulations, he moves to Ballingeary, where he works as a labourer. From there he moves to Enniscorthy, County Wexford, where he lives with Larry de Lacy. On February 24, 1915, he is arrested and tried under the Defence of the Realm Act for putting up seditious posters. But for this and a second charge of “possession of explosives” he is discharged. The explosives belonged to de Lacy.

The Volunteers appoint O’Hegarty as Commandant of Ballingeary and Bandon. During the Easter Rising, he is stationed in Ballingeary when visited by Michael McCarthy of Dunmanway to propose an attack on a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) post at Macroom. But their strength is fatally weakened and, having no reserves, they call off the attempt. In 1917, he becomes Vice-commandant of No.1 Cork Brigade. He works as a storekeeper at the workhouse but is intimidating, and clashes with the Poor Law Guardians.

During the Irish War of Independence, O’Hegarty is one of the most active in County Cork. Like others, he is exasperated with Tomás Mac Curtain’s inactivity and refusal to be more bellicose. One such is battalion commander Richard Langford, who joins with O’Hegarty’s unit to make an unauthorized raid on the RIC post at Macroom. Langford is court-martialed, but O’Hegarty continues to rise in the ranks. When a RIC Inspector is murdered, Mac Curtain condemns the shootings and calls for their end. On March 19, 1920, Mac Curtain is shot and killed in his home in Cork. The coroner blames the British establishment in Dublin, but the police never make any attempt to investigate the killings. Shortly after these events General Hugh Tudor begins the policy of official reprisals.

In January 1920, an inquiry is held into corruption alleged against “Hegarty’s Mob” or “Hegarty’s Crowd” running Cork City. O’Hegarty blames the former mayors for the charges of incompetence but remains on good terms with them.

In a raid on Cork City Hall on August 12, 1920, the British manage to net all the top brass of the IRA in Cork. In an incredible failure of intelligence, they do not identify the leadership as their prisoners. They are all released, including Liam Lynch, and O’Hegarty. Only Terence MacSwiney, the new Lord Mayor of Cork, is kept in custody and sent to England.

On February 25, 1921, the Coolavokig ambush is carried out by the 1st Cork Brigade under O’Hegarty at Ballyvourney village, on the road between Macroom and Ballyvourney. The IRA suffers no casualties; however, the number of British casualties has been disputed to this day.

The brigade commanders in the southern division retain a residual lingering resentment of Dublin GHQ’s lack of leadership and supplies. Seán Moylan, commandant of No. 2 Cork Brigade, thinks good communications with No.1 Brigade are to be vital, but little of this is seen via the organizer, Ernie O’Malley, at GHQ. At a meeting set up for April 26, 1921, when the manual of Infantry Training 1914 is produced, the document raises great anger. The meeting ends in uproar when O’Hegarty, who is “a master of invective, tore the communication and its authors to ribbons.”

O’Malley and Liam Lynch, the general, meet with O’Hegarty in the mountains of West Cork, near a deserted farmhouse, just off the main road. In the retreat that follows, the Irish take heavy casualties and leave their wounded to the good care of the British. These are the “Round-ups” in which the Irish sleep outside in order to avoid being at home when the Army calls. They are told by the Brigade to learn the national anthem of England to avoid arrest.

In East Cork brigade, O’Hegarty uncovers a spy ring. He is ruthless in the treatment of Georgina Lindsay and her chauffeur, who give away information to the Catholic clergy, but is remarkably lenient on brigade traitors within. He is allegedly not too bothered about evidence but is reminded that all executions of a traitor have to be approved by Dublin first.

O’Hegarty becomes more and more aggressive toward the establishment, using tough language to impose his will over the area. He attempts to force the civilian Teachtai Dála (TDs) for Cork to stand down, to give way to military candidates, telling the Dáil in December 1921, that any TD voting for the treaty will be guilty of treason. But Éamon de Valera is decided and overrules any interference with the Civil Government. Like the commanders, de Valera rejects the treaty but has already been defeated in the Dáil on a vote by W. T. Cosgrave‘s majority.

On February 1, 1922, O’Hegarty marries Maghdalen Ni Laoghaire, a prominent member of Cumann na mBan.

O’Hegarty is on the IRA’s Executive Council, but when there is a meeting on April 9, 1922, it is proposed that the Army should oppose the elections by force. As a result, Florence O’Donoghue and Tom Hales join him in resigning. In May, he and Dan Breen enter into negotiations with Free Stater Richard Mulcahy. A statement is published in the press asking for unity and acceptance of the Treaty. During this time, the republicans become very demoralized and ill-disciplined, but they have to gain strength before announcing independence from Dublin. The debate amongst the anti-Treaty IRA command is increasingly rancorous.

The bitter divisions split the anti-treatyites into two camps. Two motions are debated at the Army Convention on June 18, 1922. At first, the motion to oppose the treaty by force is passed. These men include Tom Barry, Liam Mellows, and Rory O’Connor, who are all in favour of continuing the fight until the British are driven out of Ireland altogether. However, one brigade’s votes have to be recounted, and then the motion is narrowly defeated. Joe McKelvey is appointed the new chief of staff, but the IRA is in chaos. While he strongly opposes the Anglo-Irish Treaty, O’Hegarty takes a neutral role in the Irish Civil War and tries to avert hostilities breaking out into full-scale civil war. He emerges as a leader of the “Neutral IRA” with O’Donoghue. This is a “loose” confederation of 20,000 men who have taken part in the pre-truce wars but have remained neutral during the Civil War from January 1923. Over 150 persons attend its convention in Dublin on February 4, 1923. By April 1923, O’Malley is imprisoned in Mountjoy Prison. In a letter to Seamus O’Donovan on April 7, he blames Hegarty for all this compromise and “peace talk.”

It has been alleged by the author Gerard Murphy that O’Hegarty had a role in the assassination of the Commander-in-Chief, Michael Collins, in August 1922, along with Florrie O’Donoghue and Joe O’Connor. It is alleged that as members of the 1st Southern Division Cork, they are actually feigning claims of neutrality but remain part of the IRB in order to set up talks towards peace and the cessation of hostilities at the start of the Irish Civil War.

Although probably an atheist during the Irish War of Independence, O’Hegarty returns to the Catholic church later in life. On forming the Neutral Group of the IRA in December 1922, he tries to unify differences in the volunteers between Republicans and the Free Staters. He communicates with the Papal Nuncio during the inter-war years in an attempt to have Bishop of Cork Daniel Cohalan‘s excommunication bill lifted. Instead, he turns to commemoration as a way to earn favour in Rome, with the dedication of a Catholic church at St. Finbarr’s Cemetery. After his wife’s passing, he becomes a close friend with Florence O’Donoghue until his own death.

O’Hegarty dies on May 31, 1963, at Bon Secours Hospital, Cork.