Justin Pascal Keating, Irish Labour Party politician, broadcaster, journalist, lecturer and veterinary surgeon, dies at Ballymore Eustace, County Kildare, on December 31, 2009. In later life he is president of the Humanist Association of Ireland.

Keating is twice elected to Dáil Éireann and serves in Liam Cosgrave‘s cabinet as Minister for Industry and Commerce from 1973 to 1977. He also gains election to Seanad Éireann and is a Member of the European Parliament (MEP). He is considered part of a “new wave” of politicians at the time of his entry to the Dáil.

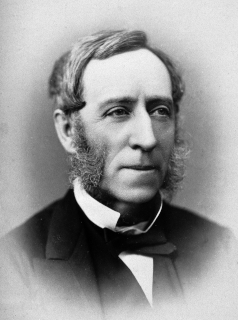

Keating is born in Dublin on January 7, 1930, a son of the noted painter Seán Keating and campaigner May Keating. He is educated at Sandford Park School, and then at University College Dublin (UCD) and the University of London. He becomes a lecturer in anatomy at the UCD veterinary college from 1955 until 1960 and is senior lecturer at Trinity College Dublin from 1960 until 1965. He is RTÉ‘s head of agricultural programmes for two years before returning to Trinity College in 1967. While at RTÉ, he scripts and presents Telefís Feirme, a series for the agricultural community, for which he wins a Jacob’s Award in 1966.

In the 1950s and 1960s Keating is a member of the communist Irish Workers’ Party. He is first elected to the Dáil as a Labour Party Teachta Dála (TD) for the Dublin County North constituency at the 1969 Irish general election. From 1973 to 1977 he serves in the National Coalition government under Liam Cosgrave as Minister for Industry and Commerce. In 1973 he is appointed a Member of the European Parliament from the Oireachtas, serving on the short-lived first delegation.

During 1975 Keating introduces the first substantial legislation for the development of Ireland’s oil and gas. The legislation is modelled on international best practice and intended to ensure the Irish people would gain substantial benefit from their own oil and gas. Under his legislation the state could by right acquire a 50% stake in any viable oil and gas reserves discovered. Production royalties of between 8% and 16% with corporation tax of 50% would accrue to the state. The legislation specifies that energy companies would begin drilling within three years of the date of the issue of an exploration license.

Keating loses his Dáil seat at the 1977 Irish general election but is subsequently elected to Seanad Éireann on the Agricultural Panel, serving there until 1981. He briefly serves again in the European Parliament from February to June 1984 when he replaces Séamus Pattison.

In the aftermath of President of Iran Mahmoud Ahmadinejad‘s “World Without Zionism” speech in 2005, Keating publishes an op-ed in The Dubliner magazine, expressing his views on Israel. The article starts by claiming that “the Zionists have absolutely no right in what they call Israel.” He then proceeds to explain why he thinks Israel has no right to exist, claiming that the Ashkenazi Jews are descended from Khazars.

Keating dies at Ballymore Eustace, County Kildare, on December 31, 2009, at the age of 79, one week before his 80th birthday. Tributes come from the leaders of the Labour Party and Fine Gael at the time of his death, Eamon Gilmore and Enda Kenny, as well as former Fine Gael leader and Taoiseach John Bruton.